By and large, there are more pictures in children’s and young adult books than in books for adults. Tabernero considers illustrations as one of the paratextual elements of this genre of fiction. Nowadays, illustrations are even more important since the proposed reader for these products is especially familiar with various audio-visual systems (videogames, online channels, TV…) (70). Next, we will explore what function illustrations traditionally had. (Genette, 1987:33).

Ventura (2004: 3) warns us of the importance of the relationship between the visual and the written word and how adequate they are to the format and dimensions in which they appear. Lewis (1999:84) establishes three functions to this genre of picture books: 1. Aesthetic, centred on image analysis. 2. Pedagogical, centred on understanding. 3. Literary, a combination of both and surmising that this type of text is a different double entity and that each part would not work on its own. The truth is people can fail to perceive the importance of these products in the last 20 to 30 years, especially if they do not work with children. There have been many research studies carried out about these types of books (for a complete list, you can refer to the annotated bibliography in Tabernero: 71) and publications such as Libro Blanco de la ilustración gráfica en España (2004) (http://www.fadip.org/archivos/libroblanco.pdf) and their new version including digital illustration (en https://adadibujantesdeargentina.org/uploads/NuevoLibroBlancoIlustracion_web.pdf) several catalogues about famous illustrators such as Ilustradores españoles (1983), Mira qué te cuento (2004), which comes with a web page to train creators https://webdelalbum.org/# and El texto iluminado (2002), as well as the Instituto Cervantes website Cien años de ilustración infantil (2004). https://cvc.cervantes.es/actcult/ilustracion/

The distinction between picture books and illustrated books is that in picture books, images are completely integrated in the development of the narrative, whereas in illustrated books, illustrations are simply complementary (Hunt, 1991, 175). One of the first issues manifested in the creation of this type of visual textual fictions is the symmetry or asymmetry, in terms of importance given to the text or images. Is the image operating for the author of the text? On the other hand, is the illustrator as important as the narrator of the text or in some cases, even more important? It is highly unlikely that we will reach an agreement and it is very possible that this type of relationship will vary depending on the genesis of the project and the verbal and non-verbal contracts between author/publisher/illustrator and other participants in the commission. In any case, what is evident is that illustrations present a different way to narrate a story, above all, with a younger audience, who would need an adult or older reader to decipher the verbal text for them.

Tabernero quotes Obiols (2004: 35 – 40) attributing five functions to images:

- To show what words do not tell

- To reinforce the textual context

- To decorate and to embellish the text

- To capture and to show pockets of the world surrounding the story

- To enrich the reader/watcher

She adds a sixth function; to mediate between the literary author and their natural readership (García Padrino, 2004:19-20). Tabernero thinks that we must add a contextual dimension to these functions, because in the 21st century, children’s literature is perceived as written and not oral, as individual and not collective, as read and not orally narrated/performed by minstrels or storytellers (74). In some way, the illustrator replaces the storyteller, taking the responsibility to show an element that would have been developed by gestures or tones in other periods of history. Given this innovative nature, Tabernero shows the need to distinguish between picture books and illustrated books in these terms, whereas Hunt showcases the disruptive influence images have in a picture book, to the linear narrative of the story (1991, 176).

https://www.culturagenial.com/es/las-aventuras-de-alicia-en-el-pais-de-las-maravillas/ (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

https://www.culturagenial.com/es/las-aventuras-de-alicia-en-el-pais-de-las-maravillas/ (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

It is important to remember that at the beginning of book illustrations in the middle ages, they had a moralizing or pedagogical purpose with the use of illuminated book of medieval texts. The birth of the picture book is traditionally placed in the 60s, in spite of previous examples, such as Alice in Wonderland by L. Carroll, Der Struwelpeter by Hoffmann, or A Apple Pie by Greenaway in the 19th century. Likewise, other 20th century examples include The Story of Babar by Brunhoff and Albums du Pére Castor by Faucher (Tabernero: 75). The visual revolution of television, commercials and cinema, in the 60s, shows evidence of the semiotic revolution brewing in narration development. However, picture books are very costly, especially when manufacturing a high-quality product, The 21st century market makes it extremely difficult to compete with big global merchandising names, such as, Disney, Nickelodeon, etc., and to sell a product that is so costly to produce.

One of the most interesting issues that arise during the production of these books is the special relationship between image and text, which includes a level of experimentation and postmodernism. These characteristics are prevalent in children’s fiction, owing to the fact that younger readers tend to be more open to new proposals and have fewer expectations (Tabernero: 78). However, the revolution in all kinds of picture books has rekindled the need to provide new ways to create fiction for young adults and even adults as well. We can quote some books for adults and young adults such as: Someday a bird will poop on you by Sue Salvi and Megan Kellie or Go The Fuck to Sleep by Adam Mansbach. If you want to have a look at picture books or illustrated books for adults, you can consult: Crossover Picturebooks, a Genre for all Ages by Sandra L Beckett or Picture This: Picture Books for Young Adults: A curriculum-related annotated bibliography by Denise Matulka.

Among the most innovative features that are included in current picture books is their metafictional or intertextual intention. Metafiction here implies that the text plays with the conventions that delimit real and unreal, word and text. Clear examples of this metafiction and intertextual quality are the classic books, such as Where the Wild Things Are by Sendak – where Max sometimes looks like Rodin’s thinker – Not now, Bernard, by McKee – in whose bookcase we see Elmer, the colourful elephant – and El libro de las M’Alicias by Obiols y Calatayud – in which we see a girl that resembles Carroll’s Alice a lot.

https://www.kalandraka.com/catalogo/album-ilustrado.html?autores=5920 (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

Illustrations warn us and sometimes point towards the errors in the text or establish a contradiction between the text and the image, for instance in Mamá fue pequeña antes de ser mayor by Larrondo & Lamartine.

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

Let us not forget that these types of books adhere to the principle of linguistic economy, perhaps supported by the fact that traditionally, children’s books should not go beyond 32 pages.

Some other highly recommended picture books in Spanish are:

WITHOUT TEXT

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- El paseo by Celia Sacido

- Caperuza by Beatriz Martín Vidal –

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- En el bosque by Ana María Matute (box format)

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- El arenque rojo by Gonzalo Moure (envelopes)

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- Museum by Javier Saenz Castán

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- Malacatú by María Pascual de la Torre

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

WITH TEXT

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- Perro y gato by Alcántar y Gusti.

- Camuñas by Margarita del Mazo Fernández

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

3. Orejas de mariposa by Luisa Aguilar

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

4. Bola de manteca by Ana Presunto e Iván Suárez

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

5. El monstruo de colores by Anna Llenas.  (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

In the next list of picture books, you will see examples that have left their mark in the global market and that have been translated into in many languages in the last few years:

- The giving tree by Shel Silverstein

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

2. The true story of the three little pigs by Wolf

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

3. The Lorax by Dr Seuss (trailer)

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

4. The day crayons quit by Oliver Jeffers (very interesting video in English)

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

Spanish version:

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

5. Ze Vais Te Manger by Jean Marc Derouen

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

6. Diary of a wombat by Jackie French

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

7. The very hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle. The Spanish version has a beautiful error in the title.

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

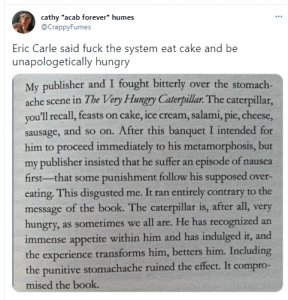

Some time ago, I came across a quote on Twitter, retweeted by Amanda Palmer by Cathy ‘Acab Forever’ Humes @CrappyFumes. Amada was/is Neil Gaiman’s partner. The quote said that Eric Carle mentioned the following issue:

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

8. Everyone poops by Taro Gomi (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

9. Charlie Chick by Nick Denchfield and Ant Parker (1977) best seller that has had a 7 million euro profit in the last 25 years.

We cannot finish this list of how images and words work together in picture books for children without mentioning a few items that Tabernero brings up:

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

a) Pictograms and interactive books. By pictograms, we are referring to the technique that consists of substituting basic words in the text by icons that refer to the concept. The purpose of these icons is to break the arbitrariness of the linguistic sign (87). There are several examples, among which we can include El libro Inquieto, which we saw in the first chapter in this book and some pop-up or lift-the-flap books, such as Elmer by McKee, or combining images, such as, Tipo Teo se disfraza by Denou, fold-out books such as La Casa de Maisy by Cousins, books with holes such as Play hide and seek with Wibby, The Pig by Inkpen, books with windows or even objects that are added to the story they narrate, bridging the gap between books and toys (89). Here, although we will probably mention it when we talk about fanfiction, we should also mention the letter-book The Jolly Postman by the Ahlberg siblings.

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

b) The editorial peritext. It describes the exterior of the book: readership, format, front and back cover, title page, annex, etc., which is normally the publishing company’s responsibility (93). This section is devoted to the double readership because a lot of this information is directed to the adult, who will filter and buy this product. One of the main features that Hunt qualifies as essential to this type of fiction is that it seems that children perceive reality in a different way than adults do. However, when it comes to pictures, the adult and children’s perspective seem to be closer than ever (1991, 17).

REFERENCES TO TICKLE YOUR FANCY :

Arizpe, E. (2015) Children Reading Picturebooks: Interpreting visual texts. New York: Routledge. This book describes the reactions and experiences of some children reading picture books. Super interesting.

Butler, C. & K. Reynolds (2005) Modern Children’s Literature: An Introduction, London: Palgrave. Chapter 4 focuses on picture books. Pages 57-58 have a useful chart for terminology, which can help you when you talk about images/pictures in your essays or journal for this module.

Genette, G. (1987) Seuils, París, Seuil. It classifies format and the functions of images in books.

García Padrino, J. (1993) Formas y colores: la ilustración infantil en España, Cuenta: Universidad de Castilla La Mancha. It tells the story of the development of illustration in Spain.

Hunt, P. (1991) Criticism, Theory, & Children’s Literature, Cambridge: Basil Blackwell. It is one of the most crucial books in terms of children’s fiction theory.

Lewis, D. (1999) ‘La constructividad del texto: el libro-álbum y la metaficción’, en PAC CASTILLO M. F. (coord.) El libro-álbum: invención y evolución de un género para niños, Caracas, Banco del libro, pp. 77 -88. It develops the importance of metafiction and intertextuality in these books.

Nodelman, P. & M. Reimer (1992) The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Boston: Ally and Bacon. Chapter 12 develops all the aspects of images and illustrations that are relevant to the analysis of picture books.

Nodelman, P, Hamer, N. & M. Reimer (2017) More words about pictures: current research on picture books and visual/verbal texts for young people, New York: Routledge. It provides new perspectives on the current approaches to this type of fiction.

Obiols, N (2003) Mirando cuentos. Lo visible y lo invisible en las ilustraciones de la literatura infantil, Barcelona: Laertes. It analyses important characteristics of illustration and how they build their meaning.

Tabernero Salas, R. (2005) Nuevas y viejas formas de contar. El discurso narrativo infantil en los umbrales del siglo XXI, Zaragoza: Prensas universitarias de Zaragoza. An essential book for this module, in which most of the information for this chapter is based.

Ventura, A. (2004) ‘Las técnicas en la ilustración infantil’, Cien años de ilustración española, Centro Virtual Cervantes pp. 1 – 4. Webpage from Instituto Cervantes, which explains the most common techniques of illustration in Spain.