Definitions and a brief summary of the history of comics in Spain

A comic is a story that is published under very distinctive parameters according to the use of particular narrative tools. It does not normally include a narrator and if it does, the narrator has very brief interventions to explain the setting and time of the story. It is normally told through dialogue that is simultaneous and usually, it does not have a clear structure. It is closer to a film script or a piece of writing for theatre than to storybooks or traditional fiction. That is why it is the perfect bridge between picture books and series/films, to which we will turn our attention to after this chapter.

Comics are told through storyboards and one or several vignettes, depending on the type of story or message wanting to be told. The visual content is just as important as the verbal and it normally includes a series of onomatopoeias, as if the comic strip was written to be read. At the same time the comic is acted out in the reader’s imagination with clearly-defined voices and sounds. The sounds combinations used may be standard, even though they may or may not be used in colloquial language or may have been invented by authors or translators. In Spain, we call them ‘little stories’ due to the way in which they originated: a little story in a journal or a magazine that was frequently published. Following this, the magazine called TBO (tebeo) dedicated a significant space for them and that is why, in Spain, they are also known as tebeos, although this is a name that is disappearing among younger generations.

The fact that they did not emerge to entertain or provide comic relief for young people is one of the most curious aspects of comics. The main function of comics in Spain at the end of the 20th century was satire, in other words, criticizing the system. The author would have been a graphic artist with a clear critical intention. This is still present in adult comics – occasionally, in children’s and young adult comics too – and it is clearly manifested in the short stories produced by newspapers. The comic books dedicated to children later developed a didactic purpose mixed with entertainment in order to make moral lessons more appealing to the younger generations. This didactic purpose moved to a more general meaning of entertainment when the industry started expanding globally. In this thesis, you can find more information about the different stages of Spanish comics and examples that you can read more about, if you are interested in this topic: https://lateinamerika.phil-fak.uni-koeln.de/fileadmin/sites/aspla/bilder/ip_2014/JuanJesusGonzalez_El_Comic_Espanol_PDF.pdf (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

https://en.todocoleccion.net/comics-grijalbo/comic-guai~x76894899

On Wikipedia there is also a database that provides many examples, including information about comics published more recently. In the middle of the 20th century there was a boom, especially with the publications of Bruguera, but once this publishing company disappeared, the smaller groups that took over didn’t manage to conquer the market with their publications such as “Bichos” and “Garibolo” and Editorial Grijalbo with “Guai!” y “Yo y Yo“. The most positive outcome of this process is that in this transition, great authors came about, such as Casanyes, Cera, Maikel, Marco, Miguel, Paco Nájera or Ramis and characters, such as Goomer, Mot y Pafman.

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC) https://comicvine.gamespot.com/top-comic-pafman-1/4000-529764/

What we cannot forget is that at the end of the 80s and beginning of the 90s, there was a rise of superheroes and manga. This remarkable increase in comic sales was influenced by international tendencies and it expanded towards adult content, leading to the opening of specialized bookshops, such as Continuará, Antifaz and Norma Cómics in Barcelona, Futurama in Valencia and Metal Hurlant and Madrid Cómics in Madrid. Following these, came Akira Cómics and Espacio Sins Entido in Madrid, Totem in Lugo and A Gata Tola in Santiago de Compostela and Joker en Bilbao. In 2008, el Salón del Cómic in Barcelona funded an award to recognize the initiatives of these bookstores. Likewise, this boom manifested among illustrators in art of comic creation magazines, such as Dentro de la viñeta, La Guía del Cómic, Krazy Comics, Nemo, Urich, Volumen; other magazines such as Amaníaco, El Batracio Amarillo, La Comictiva, Crétino, Kovalski Fly, Kristal, Paté de Marrano, Nosotros Somos Los Muertos, TMEO and other smaller publishing companies, such as Dude, MegaMultimedia, Under Cómic, 7 Monos. This booming market gave such veterans as, Alfonso Azpiri, Jordi Bernet, Carlos Giménez, Francisco Ibáñez, Jan or Max, the privilege to devote themselves to comics. The number of graphic artists working abroad was increasing: Joan Boix, Ignasi Calvet Esteban, Pasqual Ferry, Salvador Larroca (first Spaniard awarded with an Eisner for Iron Man), Esteban Maroto, Ana Miralles, Josep Nebot, Carlos Pacheco, Rubén Pellejero or Jorge David Redo.

In the first decades of the 21st century, we have witnessed a boom of publishers and events dedicated to comics. This is what the children’s publications have experienced: ¡Dibucómics! (2001) or Mister K (2004) died in the competitive market, just like the Pequeño País, which closed down in 2009. ¡Dibus! survived with co-official languages, such as Catalan. Furthermore, online guides, such as la Guía del Cómic (2000) have replaced the magazines: http://www.guiadelcomic.com/ by José A. Serrano or collective endeavours such as:

- Zona Negativa (1999) (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)- https://www.zonanegativa.com/

- Tebeosfera (2001) (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC) – https://www.tebeosfera.com/

Quoting Wikipedia, you can see that several authors work in foreign comic companies:

- U.S.A: Daniel Acuña, Gabriel Hernández Walta (Eisner awardee The Vision), Marcos Martín (Eisner awardee for The Private Eye or Daredevil), David Aja (Eisner awardee for several works for Marvel), Ramón F. Bachs, David López, Emma Ríos, Juan José RyP, El Torres, Kano, Javier Pulido, Salva Espín, Natacha Bustos, Paco Díaz, etcetera.

- France: Juan Díaz Canales and Juanjo Guarnido (authors of Blacksad, several Eisner awards), Sergio Bleda, Tirso Cons, Esdras Cristóbal, Enrique Fernández, José Fonollosa, Sergio García, Mateo Guerrero, Raule and Roger Ibáñez (Jazz Maynard), José Luis Munuera, Rubén del Rincón, José Robledo and Marcial Toledano (Ken Games), Kenny Ruiz, Alfonso Zapico, etcetera. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historia_de_la_historieta_en_Espa%C3%B1a

We cannot finish our quick overview of comics without mentioning some webcomics, such as

- ¡Eh, tío! – ehtio.es (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- El joven Lovecraft – http://eljovenlovecraft.blogspot.com/ (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- El Listo – http://listocomics.com (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- ¡Universo! (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC) – is a digital comic. We can see some photos in this document. http://www.acdcomic.es/comicdigitalhoy/25-Universo-Monteys-Mikel-Bao-acdcomic.pdf (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

The Ministry of culture awarded a Gold Fine Arts medal to the comic artists Miguel Quesada (2000), Francisco Ibáñez (2001) and Carlos Giménez (2003) and to the graphic comedian Mingote (2004). In 2007, in this field of work, they created a National Award for Comics to honour the best comic strip, written by a Spanish author that year. This has been given to Max, Paco Roca, Felipe Hernández Cava and Bartolomé Seguí, Altarriba and Kim, Santiago Valenzuela, Alfonso Zapico, Miguelanxo Prado, Juan Diaz Canales and Juanjo Guarnido, Santiago García and Javier Olivares, Pablo Auladell, Rayco Pulido or Ana Penyas. This award has given a serious boost to the art of comics.

Here is a video on what is the state of the craft of the comic in Spain up to our days:

If you are interested in comics in general, in the U.S.A., you can watch this documentary in English: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0373763/?ref_=nm_knf_t4

Alternatively, you can access the dubbed Spanish version in YouTube if you dare try it in Spanish:

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

Comics: Distinctive Features

As Scott McCloud tells us in his book Understanding Comics, there have been understudied and misinterpreted. The author uses the medium of comics to analyse these narratives, looking at what is specific in this invisible art: its relationship with other narrative methods, language and internal mechanism.

One of the defining features of this art is the narrow definition of ‘comic’, its language, its closures – a concept referring to everything that the reader has to add and the space between vignettes or boards -; the management of time, with lines that communicate feelings and sensations; the mastery of telling and showing, the development between texts and images in a way that is both complementary and parallel at the same time; its methodology; colour palettes conditioned by technology and market pressures; and of course the final assembly of every piece sustaining the narrative.

Will Eisner had defined comics as ‘a sequential art’, but for Scott McCloud this is not enough. For McCloud, comics are built with ‘illustrations and other types of images that are juxtaposed in a deliberate sequence, with the purpose of communicating information and acquiring a reader’s response” (Scott McCloud, 9).

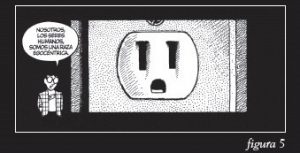

When we talk about the language used in this type of fiction, the author focuses on the concept of ‘icon’: ‘An image that is used to represent a person, place, thing or idea’ (ibid. 27). Icons are subdivided into symbols (for abstract ideas), scientific icons, language and communication (numbers, letters, symbols…) and lastly, those that are represented by their similarity to an object.

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

For McCloud, the jump between storyboards is fundamental, as it proves the ability of the narrator to help the author fill in the gaps. The author puts forward six categories between boards: moment-to-moment, action-to-action, topic to topic, aspect to aspect or completely non sequitur.

Time-management is a concern for McCloud because comics have been equated to the syntax of photograms in cinema and TV, but their mechanisms are more varied. If it is assumed in the Western World that we read from left to right and from top to bottom and narrators are going to use these directions to organize the timeline on each page. This would be called a panel and it would be a primary unit for analysis as a sign, because it shows the ways that time has been structured on a page. It also reminds us of the fact that time is represented through the way we show movement in fixed images.

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

If you want to watch an episode of a TV series from this Mortadelo and Filemón comic, you can find some episodes on YouTube. Here is an example:

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

The lines are also used for descriptions of emotions. McCloud elaborates by proving that there are different graphic symbols used in comics for this: wavy lines represent smells or a sigh, hearts for someone who is infatuated, little birds over someone’s head means they were hit, sweating means anxiety and so on (McLoud, 130).

We see a classification of picture books by the way they use their images, McCloud categorizes comics in their way to combine image and text:

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

- Illustrations

- Images for image’s sake

- Dual images where text and image are working together and inseparable

- Additional images

- Parallel images

- Montage, where words are imposed on the image,

- Interdependent images

In this link, you will find an episode of Malfada animada and you will get to know the characters of this comic strip

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

Likewise, if you are interested in getting to know the classical elements of comics, you can watch this short video in Spanish:

(CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

The relevance of comics in children’s and YA fiction

Comics were not very popular for a long time and were considered marginal, concerning the fostering of reading skills and abilities in children’s and young adults. This is a serious error of judgement, as comics bring about a lot of cultural information that will promote interaction with children and teenagers or when we just want to promote the love of reading. Opposite to popular belief, the reading of images and storyboards is not simple at all and requires the use of cognitive skills, just as interesting as the skills developed while reading plain text on a page. There was never a lack of adults telling us off as children for reading comics instead of books, although case studies have been proven that the development of the child as a reader goes hand in hand with the interaction of image and text. In fact, children start to express themselves with lines and pictures, much earlier than they do in an oral or written manner. That is why it is very important to start by reading images in any format. Comics offer a step up from picture books, even though sometimes their borders are not easily defined.

Comics have several advantages over picture books. They improve reading skills because there is a need to understand the time sequence on a storyboard. It develops the ability of memorization and understanding abstract symbols – almost every 5 to 6 year-old is capable of recognizing a lit up lightbulb as a sudden eureka moment. It fosters concentration and it helps them interpret other audio-visual media. It develops imagination because of the visual wealth in a comic. It also tends to portray characters or speech in an ingenious way that the child enjoys. It is economic and easy to acquire and manipulate, as opposed to the weight and size a book can have. This genre’s versatility makes it possible to have comics for children as young as 3 years-old.

To illustrate this with a beautiful comic for very small children, we can have a look at Puncho; you can follow this link and find it in the appendix of this book (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC): https://www.unamamanovata.com/2019/10/15/puncho-un-comic-espanol-que-fomenta-el-amor-por-la-vida-en-el-campo/

REFERENCES TO TICKLE YOUR FANCY:

Exhibition that portrays how comics have incorporated the fine arts in their boards: https://www.fundaciontelefonica.com/exposiciones/arte-en-el-comic/ (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

Berger, J (1972) Ways of seeing. Penguin and BBC: London. If you are interested in learning how to communicate with visual arts, this documentary series is vital for our current understanding of image. (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

Episode 1 – https://youtu.be/0pDE4VX_9Kk

Episode 2 – https://youtu.be/m1GI8mNU5Sg

Episode 3 – https://youtu.be/Z7wi8jd7aC4

Episode 4 – https://youtu.be/5jTUebm73IY

Groensteen, T. (2013) Comics and Narration, Martin, A. (2018) University Press of Mississippi. This book develops comics as a narrative and expands on how they develop a plot.

McLoud, Scott (1994) Understanding Comics, New York: William Morrow. – This is a review of the Scott McCloud book, which you have in the library. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-885X2008000200013 (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

Mikkonen, K. (2017) Narratology of Comic Art, London: Routledge. It develops the concept of comics as narratives.

Rauscher, A. et al (2020) Comics and Videogames, London: Routledge. It links this art to videogame development.

If you personally want to produce a comic, you have a video that can help you develop a comic in a very simple way: https://youtu.be/C8K-eDx2boQ (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC)

Recommendations for those of you who enjoy reading comics (CC-BY-ND-SA-NC):