4 Moving Forward? Rethinking Mobility, Liveability and Sustainability in the City

Aliya Sultonova; Dennis Nientimp; Eve Hamel; and Jinbao Yang

What makes a liveable city?

Mobility and liveability are core components which shape and determine people’s quality of life within urban spaces. Mobility is vital to participation in society, and the ability to navigate within and engage with our environments is a key consideration in the context of sustainable development (Hook, 2023). For example, sustainable urban design considers various modes of transportation such as cars, public transport, cycling and walking, which influence mobility and liveability in convergent and divergent ways. The concept of the ‘livable city’ evades a singular definition and can “mean many things to different people” (Balsas, 200, p. 102). Nevertheless, according to Song (2011) common considerations include “ecological environment, economic performance, human environment and public facilities” (p. 1). The broader concept of ‘liveability’ rests on ideas of immediate subjective satisfaction with one’s environment and is associated at the societal scale with “levels of equity, social stability, social engagement, crime rates” and with spaces which “nurture a shared sense of local culture” (Baobeid et al., 2021, p2). We argue that both concepts – mobility and liveability – are enhanced when considered and explored through the lenses of sustainability and equity. Sustainability attends to the long-term dimensions of the well-being of both humans and the planet by considering the balance between the social, economic, and environmental facets of development across time. Meanwhile, equity allows us to explore questions of justice and fairness within urban spaces. E.g., how geographical and other disparities significantly influence equity of access to – and within – the city (Moreno et al., 2021). Mobilising this analytical framework, this essay will explore some key challenges surrounding urban transportation planning; discussing the inequitable design of current transport systems, exploring challenges to enhancing walkability, and highlighting the importance of attending to local context to ensure accessibility and a livable urban environment for all.

Inequitable & unsustainable urban mobility systems:

Vast inequities are embedded within existing mobility systems (Scott, 2012). Millions of workers, many belonging to low-income groups, commute daily to vital locations including medical facilities, grocery stores, and warehouses using inadequate public transit systems (Dinamani et al., 2023). Simultaneously, car-centered planning & design, coupled with the distances between living, working and recreational spaces require many people to cover long distances by car. This has a direct negative impact on the urban environment, through the emission of greenhouse gases and other harmful pollutants (Kahn, 2007; Glaeser & Kahn, 2010; Ewing & Cervero, 2010). Indeed, transportation that uses fossil fuels as an energy source is a major contributor to climate change globally (Jones et al., 2023). Such mobility patterns also impact the city’s landscape more broadly, with widening roads and highways subsuming land and space which may have otherwise been used for vegetation and green space (Leyden & Fitzsimons D’Arcy, 2018). Furthermore, there are social implications of car-centric urban design and transport planning, such as reduced social interaction and lower levels of social capital. Navigating such urban spaces as a pedestrian or cyclist is often inconvenient and unsafe, the experience exacerbated by poor air quality related to traffic levels (Leyden, 2003) and disparities in accessing facilities according to citizens’ wealth and physical abilities (Sheller, 2020). The combined impacts of these issues illustrate the need for a systematic transition towards alternative urban design scenarios.

Towards sustainable mobility systems:

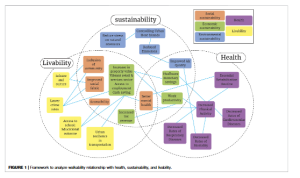

The positive health effects of walkability and its relationship to urban liveability are commonly acknowledged within academic research and public policy. However, urban planning and design systems do not often tend to target these areas (Leyden et al., 2023). Cities’ car-centred design must shift to ensure more walkable neighbourhoods as well as safe and affordable active transport options. But how can cities work towards actioning such transitions, and what are the demonstrable benefits? To increase liveability, considering walking as a key mode of transportation is crucial. As humanity’s first mode of transportation, walking is at the heart of sustainability (Hynes, 2022). It is a transportation mode that does not require external energy sources and simultaneously helps to keep people healthy, happy, and active (Baobeid et al., 2021, p5). Further, enhancing walkability improves how hospitable a place is and addresses myriad sustainability concerns in relation to the economy, society, and the environment (Baobeid et al., 2021, p5). When developing an urban walking scenario, one must satisfy four main conditions, in that the route must be useful, safe, comfortable, and interesting. All are essential, and none alone is sufficient (Speck, 2013). The interconnected effects of walkability on sustainability, liveability and health are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 explores how walkability serves individual health, community liveability, and sustainability (Baobeid et al., 2021, p2)

In addition to enhancing walkability, cities must also facilitate safe cycling and ensure the provision of accessible public transport (Sheller, 2020). To do so, they need to provide a matching infrastructure of bike lanes, shaded walking spaces, and a far-reaching public transport network with convenient time intervals and prices (Favelle & Plant, 2009; Sheller, 2020; Scott, 2020). The benefits of integrating such mobility links are increased social interactions which foster trust, health, happiness, and social capital (Kent et al., 2017; Leyden, 2023; Putnam, 2000) and have a positive environmental impact (Sheller, 2020; Scott, 2020). Furthermore, private car ownership and the related injustices driven by market-driven neoliberal capitalism can be offset by subsidising public transport routes for social and economic benefits. If implemented, these changes would lead to a knock-on decrease in air pollution, less noise, more space for walking and recreation, and a reduction in the financial burden of sustaining cars. Whichever approach is mobilised to achieve such a transition, safe and accessible transport for all should be guaranteed to ensure equity.

Ensuring accessible local mobility systems:

To address different citizens’ needs regarding transport, mobility and liveability, varying abilities and other contextual limitations must be considered (Ranchordás, 2020). As such, removing barriers for disabled and other citizens by including their needs is crucial. A way to do so is to empower underrepresented groups by including a broad range of stakeholders in the planning processes central to transitions (Hogan et al., 2015; Tokar, 2018). Participation in policy, planning and access to subsidies should also be facilitated. However, one solution might not fit every context. For example, walkability may not be the optimum focus as an alternative to other means of transport in contexts where distances between destinations are longer, temperatures are higher, and where the landscape contains barriers such as mountainous or desert terrain. Therefore, adopting a place-specific, locally attuned approach which acknowledges local circumstances through bottom-up communication might enable a more equitable transition towards more sustainable mobility systems (Feola & Jaworska, 2019; Rotmans et al., 2009). Finally, to conclude, when discussing sustainable transitions towards enhanced mobility and liveability, one should also attend to the international differences in people’s access to both. As such, the needs of migrants and refugees should not be omitted from debates and discussions around mobility and liveability, urban or otherwise (Sheller, 2020). Facilities such as borders and passport checkpoints are also part of local and global mobility infrastructures and transport systems and should not be ignored by researchers (Sheller, 2020; Vukov & Sheller, 2013). In sum, there are promising frameworks under which the transition to more accessible, mobile, and liveable cities might be realised. However, increasing awareness and implementing transitions in practice both warrant more attention going forward.

References:

Balsas, C. (2004). Measuring the liveability of an urban centre: An exploratory study of key performance indicators. Planning Practice & Research, 19(1), 101–110.

Baobeid, A., Koç, M. and Al-Ghamdi, S.G., (2021). Walkability and its relationships with health, sustainability, and liveability: elements of physical environment and evaluation frameworks. Frontiers in Built Environment, 7(721218), 1-17.

Cattaneo,C., Kallis, G., Demaria, F., Zografos, C., Sekulova, F., D’Alisa, G., Varvarousis, A., And Marta Conde. (2022) A Degrowth Approach to Urban Mobility Options: Just, Desirable and Practical Options. Local Environment, 27(4), 459–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2022.2025769.

Dinamani, A., Schneider, K., Zubin, P., Porter, J. (2023) Delivering on equity with mobility technologies. Proprietary Research Database (Deloitte). https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/transportation-equity.html

Ewing, R., & Cervero, R. (2010). Travel and the built environment: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(3), 265–294.

Favelle, H., & Plant, L. (2009). The importance of shade for healthy places and spaces, Australian Planner, 46:2, 16-17, DOI: 10.1080/07293682.2009.9995304

Giuseppe, F., & Jaworska, S. (2019). One Transition, Many Transitions? A Corpus-Based Study of Societal Sustainability Transition Discourses in Four Civil Society’s Proposals. Sustainability Science, 14(6), 1643–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0631-9.

Glaeser, E. L., & Kahn, M. E. (2010). The greenness of cities: Carbon dioxide emissions and urban development. Journal of Urban Economics, 67(3), 404–418.

Hogan, M. J., Johnston, H., Broome, B., McMoreland, C., Walsh, J., Smale, B., Duggan, J., Andriessen, J., Leyden, K. M., Domegan, C., McHugh, P., Hogan, V., Harney, O., Groarke, J., Noone, C., & Groarke, A. M. (2015). Consulting with citizens in the design of wellbeing measures and policies: Lessons from a systems science application. Social Indicators Research, 123(3), 857–877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0764-x

Hook, H. (2023). Transport, mobility and equity, SP6134 Independent Study.

Hynes, M. (2022). Walk a Mile in My Shoes! An Autoethnographical Perspective of Urban Walkability in Galway. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 51(5), 619-644.

Jones, M.W., Peters, G.P., Gasser, T. et al. (2023) National contributions to climate change due to historical emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide since 1850. Science Data, 10(155). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02041-1

Kahn, M. E. (2007). Green cities: Urban growth and the environment. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Leyden, K. M. (2003). Social Capital and the Built Environment: The Importance of Walkable Neighborhoods. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1546–1551. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1546.

Leyden, K.M., & Fitzsimons D’Arcy, L. (2018). Rethinking zoning for people: utilizing the concept of the village. One Hundred Years of Zoning and the Future of Cities, 77-93.

Leyden, K. M., Goldberg, A. , & Michelbach, P. (2011). Understanding the Pursuit of Happiness in Ten Major Cities. Urban Affairs Review, 47(6), 861–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087411403120.

Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C., & Pratlong, F. (2021). Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities, 4(1), 93-111.

Ranchordás, S. (2020). Smart Mobility, Transport Poverty and the Legal Framework of Inclusive Mobility. Smart Urban Mobility: Law, Regulation, and Policy, in Finck M., Lamping, M., Moscon, V., & Richter, H., MPI Studies on Intellectual Property and Competition Law. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-61920-9_4.

Rotmans, J., and Loorbach, D. (2009). Complexity and Transition Management. Journal of Industrial Ecology 13(2), 184–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9290.2009.00116.x.

Scott, N. (2012), ‘How car drivers took the streets: critical planning moments of automobility’, In P. Vannini, L. Budd, O. B. Jensen, C. Fisker and P. Jiron (eds), Technologies of Mobility in the Americas, New York: Peter Lang, pp. 79–98.

Scott, N. (2020), Assembling Moral Mobilities, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Sheller, M. (2020). Mobility Justice. In Handbook of Research Methods and Applications for Mobilities, 11–20. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.elgaronline.com/display/edcoll/9781788115452/9781788115452.00007.xml.

Song, Y. (2011). A livable city study in China using structural equation models.

Speck, J. (2013). Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time. New York: North Point Press.

Tokar, B. (2018). On the evolution and continuing development of the climate justice movement. In Routledge Handbook of Climate Justice. Routledge

Vukov, T. and Sheller, M. (2013). Border work: surveillant assemblages, virtual fences, and tactical countermedia, Social Semiotics, 23 (2), 225–41