3 Powering Your Community

Ilah Joos; Junyu Zhang; and Karl-Ander Kasuk

Introduction:

Sustainable energy transitions have gained increased attention among policymakers, researchers, and other stakeholders. Increasingly, proponents emphasise the important role of citizens within such transitions across scales. To strengthen and ensure citizen participation in energy transitions, decentralisation of decision-making and enhanced mechanisms for public engagement must be a key focus. A participatory energy transition has two primary aims: local ownership and inclusive decision-making (Wahlund and Palm, 2022). These aims capture the broader motivation, to increase public and democratic engagement in the overall transition process and to make the transition more equitable by involving citizens in discussions surrounding their future. When communities possess a sense of ownership over the transition, they are more likely to buy into its necessity and work together to achieve it. Communities can achieve the aims of local ownership and inclusive decision-making via social movements, formal representation in policy processes, and/or through material forms of participation. However, few clearly defined transition pathways for local energy systems exist, and as transitions unfold, tensions tend to arise around existing institutions and values. In this essay, we explore several potential pathways to participatory energy transitions, and briefly reflect on the debate surrounding civil disobedience and the rule of law in the context of energy transitions.

Energy Democracy and Energy Citizenship:

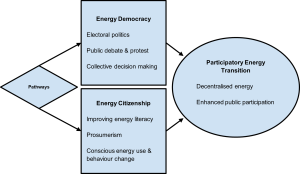

Within the academic and policy literature surrounding participatory energy transitions, two distinct pathways appear consistently. Energy Democracy (ED) and Energy Citizenship (EC) are both underpinned by the goal of enhancing participation within energy transitions, but their direction and methods tend to differ (Figure 1) (Wahlund and Palm, 2022).

Figure 1. Possible Energy Democracy and Energy Citizenship actions towards the Participatory Energy Transition

In general, EC is considered a more ‘bottom-up’ approach, which seeks to influence change from the citizen level directed towards the wider community and government. ED, on the other hand, seeks to direct change from the top down, often via political process. The role of social movements and civil society initiatives, and the significance of formal processes for engaging citizens in advancing energy transitions, are discussed in both literatures. The ED literature draws upon democracy frameworks, often connected to political action, to understand the demands of rational social movements. However, the EC literature tends to draw upon models of citizenship to highlight the importance of rights and responsibilities as expressed within social movements (Wahlund and Palm, 2022).

Inclusiveness and participation:

A fundamental requirement in transitioning towards more decentralised energy systems is the broadening of citizens’ deliberate participation in both energy policymaking and related initiatives at the community level. Sustainability challenges often arise due to unequal power relations within and surrounding incumbent energy systems, in which energy providers wield enormous power in relation to users (Avelino and Wittmayer, 2015; Gailing, 2016). These unequal power structures are embedded within the centralised design of current energy systems globally, which allow suppliers (state-owned or private) to control energy pricing and access, in turn marginalising users through bargaining power. Encouraging citizens’ participation in energy systems and governance, therefore, can equip users with a stronger voice in relation to energy policy, and empower them to challenge the structural imbalances within energy systems. Moreover, citizens’ agency can be developed and have more profound impact through deliberate participation. Individuals need to feel empowered as actors or stakeholders beyond the label of ‘energy users’ to become initiators of community solutions, facilitators of energy schemes, and managers of new energy forms such as solar (Inês et al., 2020). In addition to greater individual participation, collectives or agencies can also play a significant role in shaping energy institutions and ushering in transformative changes (Palm, 2021).

Civil Disobedience:

Considering the urgent need for sustainable energy transitions, a key question which has been raised is whether the pursuit of energy citizenship should include non-violent acts, which often transgress the law, in protesting unsustainable and inequitable energy systems. Many authors discuss issues surrounding the validity and merit of civil disobedience in addressing different societal problems (Scherhaufer, 2021; Lefkowitz, 2007; Capstick, 2022; Penders, 2020). This literature should inform any exploration of these questions in the context of energy transitions. Both justification and counterarguments can be provided for civil disobedience and related non-violent acts. For instance, one could argue that civil disobedience is necessary to achieve progressive change, particularly in the context of existing extractive and environmentally destructive industries and practices which are central to the current, carbon-centric energy sector. Additionally, conflicting rights, duties and principles exist. For example, an act that does not comply with the rule of law may be in line with environmental justice or human rights principles. Equally arguable, however, is that such acts would be unlawful and might simultaneously jeopardise individuals and the broader movements and campaigns they seek to progress. Notably, people have vastly divergent opinions on what is acceptable and what is not (Scherhaufer, 2021). These questions, we believe, will become increasingly pertinent. As such, further research and exploration on such frictions are required in the context of pursuing more equitable and sustainable energy systems.

Communication and Participation

In exploring various pathways and actions towards participatory energy transitions, our final consideration is concerned with the ability of research to inform action and decision-making at different scales. A key factor in the applicability of research on transitions is whether it is digestible and easily understood by target audiences. So, whilst we have observed the distinction within academic literature between the concepts of ED and EC, one will likely come to dominate and subsume the other within public and policy realms. At the European Commission level, citizen-driven actions seem to focus on EC topics but include aspects of ED such as collective participation and decision-making (European Commission, 2023). Therefore, an umbrella term such as Participatory Energy Transition, per Wahlund and Palm (2022) could be used to include a context-specific combination of EC and ED. While advancing EC in different communities differs mostly in method and extent, pursuing ED is complex on a whole other level. For example, public engagement might be complicated and constrained in countries which rely on their energy sector for a significant portion of their revenue or consider the reliability of the energy sector to be a central part of the country’s national security (Silvast and Valkenburg, 2023). Nevertheless, in situations of crisis, EC can prove more reliable than a centralised energy system. This can be seen in the context of Ukraine, where wind energy has been central to energy provision in response to damaged central power stations amid current conflict (Ambrose, 2023).

Conclusion

In sum, citizen participation will be crucial to achieving structural changes within global energy systems. Considering the complexity of energy transitions regarding technological constraints, institutional barriers, and justice concerns, more research is urgently needed to further unpack viable transition pathways and potential challenges. Despite constraints, EC and ED must be encouraged as much as possible at scales accessible to individual communities. In doing so, inclusivity, sustainability, and equity must be central considerations. The decentralisation of energy system governance would undoubtedly enhance the sustainability and stability of systems at large, and ultimately demystify energy generation and provision to societies, increasing public interest and engagement in seemingly mundane critical infrastructure.

References

Ambrose, J. (2023) ‘Ukraine built more onshore wind turbines in past year than England’, The Guardian, 28 May. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/28/ukraine-built-more-onshore-wind-turbines-last-year-than-england (Accessed 6 June 2023).

Avelino, F. and Wittmayer, J.M. (2015) ‘Shifting Power Relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective’, Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), pp. 628–649. doi:10.1080/1523908x.2015.1112259.

Capstick, S. et al. (2022) ‘Civil disobedience by scientists helps press for urgent climate action’, Nature Climate Change, 12, pp. 773-777. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-0146-y.

European Commission (2023) ‘Energy communities’. Available at: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/markets-and-consumers/energy-communities_en (Accessed 6 June 2023).

Gailing, L. (2016) ‘Transforming Energy Systems by transforming power relations. insights from dispositive thinking and Governmentality Studies’, Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 29(3), pp. 243–261. doi:10.1080/13511610.2016.1201650.

Inês, C. et al. (2020) ‘Regulatory challenges and opportunities for collective renewable energy prosumers in the EU’, Energy Policy, 138, p. 111212. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111212.

Lefkowitz, D. (2007) ‘On a Moral Right to Civil Disobedience’, Ethics, 117(2), pp. 202-233. doi:10.1086/510694.

Palm, J. (2021) ‘The transposition of energy communities into Swedish regulations: Overview and critique of emerging regulations’, Energies, 14(16), p. 4982. doi:10.3390/en14164982.

Penders, B. and Shaw, D.M. (2020) ‘Civil disobedience in scientific authorship: Resistance and insubordination in science’, Accountability in Research, 27(6), pp. 347-371. doi:10.1080/08989621.2020.1756787.

Scherhaufer, P. et al. (2021) ‘Between illegal protests and legitimate resistance. Civil disobedience against energy infrastructures’, Utilities Policy, 72, doi:10.1016/j.jup.2021.101249.

Silvast, A. and Valkenburg, G. (2023) ‘Energy citizenship: A critical perspective’, Energy Research & Social Science, 98, p.102995.

Wahlund, M. and Palm, J. (2022) ‘The role of Energy Democracy and energy citizenship for Participatory Energy Transitions: A comprehensive review’, Energy Research & Social Science, 87, p. 102482. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2021.102482.