Chapter 2: My Coming into Public Life and My Support for Isaac Butt

I was drawn into public life in a rather strange fashion. At the time the cattle plague[1] threatened to ruin the graziers a very prominent able man in my neighbourhood, John Paul Byrne, J.P., who held many public positions in his time, and who lost his seat in the Dublin Corporation for voting against granting the Freedom of the City to Parnell and Dillon, attended in the Corn Exchange to canvass for support for a rate in aid scheme to compensate the graziers for their apprehended losses, and he got men to listen to him (he was an eloquent talker) on the ground that if cattle failed the graziers would be driven to tillage and would flood the market with cheap produce. I happened to be a listener, and when he had silenced or convinced his audience I quietly tackled him and asked some questions that he found it difficult to answer. So, to get rid of the trouble and to put me aside he laid his hand on my arm in a very patronising way and said: “My dear fellow, I am in a hurry and have no time to listen to you making a speech.” I was so annoyed that I retorted: “Well, if you do not listen to me now you will hear from me in the press.” Before I left Dublin that evening I wrote my first public letter and I have been scribbling on and off ever since.[2] I had a good many notions on land reform jotted down when Mr. Butt[3] published his Irish People and Irish Land,[4] so I laid my own work by and determined to work through him, and I got to his side at the first opportunity.

After defending the Fenians in the Law Courts,[5] Mr. Butt evidently turned his mind to consider, and to remedy if possible, the grievances and tyranny that drove such brave, single-minded men into revolt.[6] He published two books, his Plea for the Celtic Race and The Irish People and Irish Land, which excited a good deal of public attention.[7] He then called a public meeting or conference in the Rotunda[8] to consider the land question, and he there started a new Tenants’ League.[9] A. McKenna,[10] a Northern journalist, was the only public man of note that appeared with Mr. Butt at that meeting. We had some remarkable speeches delivered by Father Quaide of O’Callaghan’s Mills, Mr. Byrne, a grazier, and Tom Bracken, a noted Fenian.[11] I joined the League and made Mr. Butt’s acquaintance. There was a working committee or council appointed composed of any members who wished to hand in their names with the membership fee of one pound. I handed in mine. Mr. Butt got a free meeting room in Harrington Street from Mr. Tristram Kennedy,[12] an ex-M.P. Some of the members took stock of my public letters, and I was pressed to attend all the weekly meetings, which I did, and Mr. Butt and I were on these occasions thrown together a good deal. I happened to be a more advanced land reformer than he was at that time, and I was driven to find arguments to justify my contentions. He commenced as a lease-holder, and I had some trouble to get him on to the three Fs.[13] After the Fenian flag was pulled down,[14] Sir John Gray[15] in the Freeman’s Journal entered on a very active crusade against the anomalies and abuses of the established Church. This was probably inspired by the Government to prepare the way for the Disestablishment which followed in 1869.[16] Gray then took up the agitation of the land question to prepare the way for a coming Land Bill. He called a conference in the Mansion House[17] which was well attended by men from all parts of Ireland. Mr. Butt and a contingent from his League attended, and after a rather animated discussion, a platform was agreed upon. The few Farmers’ Clubs in Ireland were requested to hold meetings, but the Fenians attacked the farmers’ meeting in Limerick, and, as Sir John Gray stated years after, spoiled the land legislation of 1870.[18]

After the Church Act passed in 1869, the Act of Union was so infringed upon by the Church Disestablishment that many leading Protestants assisted Mr. Butt in founding the Home Government League in 1870.[19] The Land Act of 1870 was a very halting measure, but its chief blot was that the majority of the occupiers could contract themselves out of its provisions.[20] The landlords set to work to grant leases or to extend or to vary the terms of the tenancies, and in every case to force the tenants to contract themselves out of the act. The Duke of Leinster was amongst the first to propound the fateful “Leinster Lease.”[21] All the legal ingenuity in the country was requisitioned to make this a model instrument for evading the Land Act. The authorities of Maynooth College led by Dr. Walsh, Archbishop of Dublin,[22] were amongst the first to protest against this document. Inspired by Cahill, K.C., and Robertson of Naraghmore,[23] a Scotsman, a Tenants’ Defence Association was started in Athy.[24] Mr. Butt’s attention was at the time centered on the building up of the Home Rule League organisation, his Tenants’ League of 1868 having lapsed on the passage of the Land Act. I put myself at once in communication with the Kildare men and started a branch of the tenants’ organisation in Dublin. With the aid of Kelly of Donabate, Reilly of Artane, Grehan of Lahaunstown, and all branches of the reliable O’Neill family, John Fitzsimons, Tom McCourt and others, I got a fairly good centre started in Dublin. Mr. Butt at my request attended some of our meetings and after a little time it was decided to start a central Tenants’ Association for all Ireland and this grew to be a great rallying point for all the leading men of the time.[25] We had annual conferences of many delegates from north and south, east and west. Mr. Butt threw himself into the work of land reform in the most determined way.[26] He drafted land bills and had them discussed, and amended or altered, at the conferences before introducing them to Parliament. He worked the Home Rule question on Grattan’s lines but without the military volunteers. He struggled hard to get the natural leaders of the people, which in Ireland meant the landlords and the clergy, to rally round the national centre which he established, but they failed to come and the old man’s giant intellectual labours drafting bills and expounding Ireland’s grievances were wasted on a demoralised, denationalised, and divided people. He succeeded in so far that he drew the Irish parliamentary representation from under the British whips of English parties, but many of the men who professed to represent Ireland only meant to magnify their own personal importance and had no faith in their own professions. After seven years existence the great body of the members who formed the Butt Party only earned for themselves the soubriquet of “Nominal Home Rulers.”

The previous order of Parliamentary politics, as expressed by the Irish Catholic Hierarchy and Sir John Gray in the Freeman’s Journal, which the Butt movement supplanted, did not come publicly into line with Butt’s work until the Home Rule conference of 1873 and even then they were never really incorporated with it. A notable but still only a small section of Protestants, led by Professor Galbraith,[27] joined in Butt’s demand for Federalism, and some of them dropped back soon to their old moorings with the Garrison Party.[28] Still, whoever writes the history of that time will find a few outstanding men of deep national instincts who were not only sincere but uncompromising, staunch Irish nationalists, like Galbraith, the Webbs,[29] McNeil[30] and a few others.

Butt’s efforts to lead all the inhabitants of Ireland on the lines of nationhood was unique and herculean, and for a man of his age, stupendous. He appealed to the landlords to rally round him as they did around Grattan in 1782 on the national question. He appealed to the farmers and labourers to rally round on the land question. He appealed to the cities to rally round and claim the rights of free citizens, and he appealed to the Catholic Hierarchy to rally round him on the free education question. He drafted bills and expounded arguments on all these questions for all the people of Ireland, and he did all this work on such an exalted standard that Michael Davitt once exclaimed after going over Butt’s work, that it would be simply impossible for any man to find a phase of the Irish question which was not elucidated in a superior manner by Mr. Butt.

But the fates were against him so far as immediate success was concerned. Ireland was quiet, business was booming, and most people seemed to be so busy raising rents and taking lands and leases at inflated prices and making settlements on a universal credit system, that there was no real attention paid to public work. The landlords were opposed to his land agitation work. The people were doubtful about the bona fides of the landlords on the Home Rule question. The Protestant Home Rulers and the Catholic clergy were suspicious of each other, so without some special impetus the Butt movement could scarcely succeed even partially.

I got so close to Mr. Butt that I was invited to many of his private meetings, so I had an opportunity of seeing all the different sections under fire. I was so convinced that he was bound to fall under the weight of such an impossible task that I quietly urged him to retire, but his heart was so much in the work of his mission that he seemed to be incapable of contemplating retirement. The end came rather suddenly. His great brain gave way under the terrible strain of overwork, and his death occurred soon after in 1879.

- Increased cattle imports to Britain from continental Europe had brought an epidemic of cattle plague, or rinderpest, in 1865, which resulted in the death or slaughter of more than 250,000 animals. In Ireland, the protection provided by the Irish Sea and an emphasis on cattle export meant that the herds mainly escaped the plague bar a few isolated outbreaks (Adelman 2015). ↵

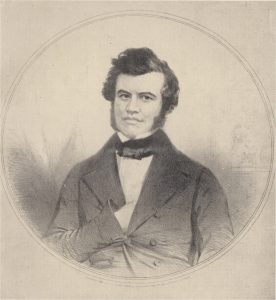

- Kettle continued as a prolific writer of letters to the newspapers of the time (Kettle 1885). ↵

- Isaac Butt (1813-79) was the son of a Co. Donegal Church of Ireland parson. Educated at the Royal School in Raphoe, Co. Donegal, and Trinity College, he became a journalist, an editor, a distinguished barrister, and a professor of political economy at Trinity College. Butt entered Parliament initially as a Conservative MP, serving for Youghal from 1852 to 1865, and then for Limerick as leader of the Home Rule MPs, from 1871 until his death in 1879. The Great Famine and its aftermath caused Butt to recognise that land reform was essential to create a more equitable relationship between Protestant landlords and the Catholic tenant farmers who comprised the majority of the population. As a highly regarded barrister, Butt gained popular support for his efforts on behalf of Fenian prisoners in the late 1860s. In 1870 Butt formed the Home Government Association, followed by the Home Rule League in 1873 (DIB 2009, ‘Butt, Isaac’; Kelley 2020). ↵

- Isaac Butt, The Irish People and the Irish Land: A Letter to Lord Lifford (Dublin: John Falconer, 1867). ↵

- The planned Fenian uprising of March 1867 had been a failure mainly due to the strength of the British forces and their infiltration of the Fenians. Butt, a highly regarded barrister, had previously defended prominent Young Irelanders (such as William Smith O’Brien and Gavan Duffy) following the Rebellion of 1848 and he gained further popular support by defending Fenian prisoners in the late 1860s. ↵

- The Famine had weakened Butt’s support for unionism and his embrace of Fenianism in the 1860s was the final stage of his political transformation. He threw himself into the cause of amnesty for the prisoners by founding the Amnesty Association in 1870. He was later quoted as saying: ‘Mr. Gladstone said that Fenianism taught him the depth of Irish disaffection. It taught me more. It taught me the depth, the passionateness and sincerity of the love of liberty and of fatherland which misgovernment had turned into disaffection’ (Bew 2007, 271; Cork Examiner, 19 November 1873). ↵

- Butt published Land Tenure in Ireland: A Plea for the Celtic Race in 1866. This brief book, which argued that Irish farmers should be granted long periods of fixed tenure on their rented land, was criticised by prominent Irish landowners, including Lord Lifford (the Deputy Lieutenant for Donegal and a member of the House of Lords), who called the proposal ‘communistic’ and an infringement on the rights of landowners. Butt defended his ideas the next year in his 300-page-long The Irish People and the Irish Land (1867), attacking the landlords’ power of eviction and accusing them of treating the Irish people as ‘belonging to a conquered race’ (Butt 1866; Butt 1867; Kerrigan 2020, 89). ↵

- The Rotunda, on Rutland Square (now Parnell Square) in central Dublin was a venue that hosted public meetings, balls, and concerts. ↵

- This was established in 1868 and lapsed in 1870 on the passage of the Land Act. ↵

- Andrew Joseph McKenna (1833-72) was appointed editor of the liberal Catholic newspaper the Ulster Observer in 1862. His acclaimed essays and powerful speaking ability brought him public attention, but his liberal outlook annoyed the newspaper’s owners. When he was fired in 1868 he launched a new paper, the Northern Star. He died prematurely at the age of 38 (DIB 2009, ‘McKenna, Andrew Joseph’). ↵

- The Fenian Thomas Bracken came to public attention towards the end of 1869 when he took a prominent part in the collection of money for the defence of Robert Kelly, who had been arrested for the shooting of accused Fenian spy Thomas Talbot. He became part of the finance committee of the Amnesty movement that had been established in 1868. A tailor by occupation, he became a central figure in the Dublin organisation throughout the 1870s and oversaw communication with England and America. He was listed by the Dublin Metropolitan Police as one of the ten most prominent Fenians in Dublin between 1876 and 1879 (Shin-ichi 1992). ↵

- Tristram Edward Kennedy (1805-85) was a lawyer, land agent, and politician. His early career was concentrated on the reform of law and legal education, but it was his reforming work as a land agent in Co. Monaghan during the Great Famine that won him the admiration of Catholics and the Tenant League. In his work as an independent politician, he came to represent the interests of poor Catholics in Parliament and his contributions were concerned largely with landlord and tenant matters and national and industrial education (DIB 2009, ‘Kennedy, Tristram Edward’). ↵

- First issued by the Tenant Right League in its campaign for land reform in the 1850s, the Three Fs were free sale, fixity of tenure, and fair rent. Fair rent was defined as ‘payment to the landlord of a just proportion of all profits which could possibly be made on the farm by an industrious tenant.’ Butt had favoured the introduction of leases of 60 years (Casey 2018, 140; Connaught Telegraph, 19 January 1878). ↵

- A reference to the failed Fenian Rising and the capture of the flag of the Fenians at Tallaght on 5 March 1867. ↵

- Sir John Gray (1816-75) was the owner of the Dublin Catholic newspaper the Freeman’s Journal. Despite being brought up a Protestant, he made a parliamentary career out of his association with the Catholic hierarchy and advocated for tenant rights. He was an active member of the National Association of Ireland, which had been formed in 1864 under the initiative of the Catholic archbishop of Dublin, Paul Cullen. Its role was to promote Catholic interests and, in particular, the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland and his arguments for Church disestablishment were seen as one of the main influences in persuading Gladstone to address this issue (DIB 2009, ‘Gray, Sir John’). ↵

- The census returns of 1861 had confirmed what had already been widely known, that is, that adherents of the Church of Ireland, the established church since the seventeenth century, comprised only 12 per cent of the population. Gladstone’s proposals for the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland were carried by the House of Commons (Irish Church Act of 1869), while opposition to it by the Conservative government led to a general election, which Gladstone won (APCK 2019). ↵

- The Mansion House on Dawson Street, in central Dublin, was the mayor’s residence as well as a popular meeting venue. ↵

- The 1870 Land Act was not seen as a settlement of Irish issues and so disturbances and agrarian crime continued to provoke much alarmed commentary. ↵

- This was the Home Government Association, which was founded on 1 September 1870. ↵

- The passing of the 1870 Land Act gave Irish tenant farmers the right to be compensated in the event of eviction for improvements they had made to the property during their tenancy. While the act was important and symbolic in that it breached the absolute rights of property holders that had existed, it was still possible for landlords to circumvent the provisions of the legislation by raising rents or introducing new leases with restrictive clauses. In this way landlords were entitled to contract out of the operation of the act, thereby depriving their tenants of its benefits. In addition, even though the act offered limited protection for small tenants from exorbitant rents by allowing them to sue their landlords, most small tenants lacked the resources to do this until the Land League began to provide them with support starting in 1879. ↵

- The Duke of Leinster was one of the first Irish landlords to attempt to deprive tenants of their entitlements under the 1870 Land Act. The ‘Leinster lease,’ as it came to be known, included restrictions that sidestepped the provisions of the Land Act by requiring tenants to forgo compensation for improvements they had made. Local opposition to this development led to the founding of the Tenants’ Defence Association in Athy (Casey 2018, 130). ↵

- William Joseph Walsh (1841-1921) was the Catholic archbishop of Dublin from 1885 until 1921. He had been president of St. Patrick’s College Maynooth and had achieved a high profile in the areas of land law and education. His desire to keep the Church in touch with the people led to his later identification with the Land League and radical nationalism (DIB 2009, ‘Walsh, William Joseph’). ↵

- Thomas Robertson was a grazier from near Athy, Co. Kildare (Casey 2011, 152). ↵

- The Athy Tenants’ Defence Association was the first in a new wave of tenants’ defence associations. It was set up in local opposition to the Leinster lease and held its first meeting on 19 November 1872 (Leinster Express, 23 November 1872; Kildare Nationalist, 29 January 2021). ↵

- The aim of the Central Tenants’ Defence Association was to link existing tenants’ defence and farmers’ associations across Ireland in order to bring collective pressure to bear on Home Rule MPs to achieve tenant rights and effective land reform. In a letter to the Wicklow Tenants’ Defence Association, dated 21 February 1873, Kettle writes: ‘I am in communication at present with fourteen clubs and associations and am about to open communication with an equal number in the South, for the purpose of getting a conference of deputies from all the tenant bodies in Ireland to meet in Dublin to decide upon what the platform cry of the agitation of all Ireland should be and to establish a Central Tenant League − this will be altogether apart from the County Dublin Association’ (Leinster Express, 1 March 1873). Newspaper coverage of communications, meetings, and national conferences relating to tenant right activism during the period 1873-79 attest to the constant presence and coordinating role of Kettle as honorary secretary of both the Dublin and central organisations. A mechanism by which tenant farmers could articulate their disappointment with the 1870 Land Act, the establishment of these associations also reflected increased participation in the democratic process following the Secret Ballot Act of 1872 (Casey 2018, 132). ↵

- Butt became a prominent supporter of the land reform cause stating in 1876: ‘The more I study and reflect on the Irish land question, the more I am convinced that it cannot be settled except by a measure that will provide fixity of tenure and an equitable adjustment of rents’ (Bew 2007, 297; Connaught Telegraph, 23 September 1876). ↵

- Joseph Allen Galbraith (1818-90) was a professor of experimental philosophy and a proponent of Home Rule. A friend of Butt, he was a founding member of the Home Government Association in 1870 and was supposed to have come up with the phrase ‘Home Rule’ for the emerging movement, which was strongly Protestant at that time (DIB 2009, ‘Galbraith, Joseph Allen’). ↵

- This seems to be a contemporary term for supporters of the union. ↵

- This could refer to Alfred John Webb (1834-1908), a radical reformer and nationalist who never joined the Land League but supported it strongly in his words and actions and served as treasurer of the National League (DIB 2009, ‘Webb, Alfred John’). ↵

- This is possibly a reference to John Gordon Swift MacNeill (1849-1926), an Irish Protestant nationalist politician and MP (1887-1918), law professor at the King’s Inns, Dublin, and the National University of Ireland, and a well-known author on law and nationalist issues (Wikipedia 2022, ‘J. G. Swift MacNeill’). ↵