Chapter 4: The 1880 Election – Parnell’s Election and My Defeat in County Cork

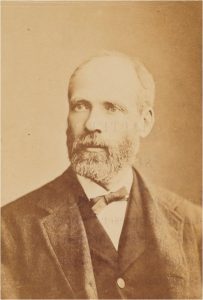

Parnell and Dillon, with Healy[1] as their secretary, were in America when the 1880 Election came on,[2] and Davitt, Biggar,[3] O’Kelly,[4] James F. Grehan[5] and I, with a good many others, went to Cork to meet Mr. Parnell on his return. Some arrangements had been made about contests and candidates, chiefly by Messrs. Davitt and Biggar. I made Biggar’s acquaintance in Cork. I had Cork County arranged and was in communication with leading Tenant Right men in other parts of the country. Parnell travelled part of the way to Dublin in different carriages in order to learn all about the state of affairs. A meeting was held next day in the League rooms, but there was no money to fight the Election. Mr. Davitt had absolute control of the League treasury,[6] and he contended that the money was not subscribed for Parliamentary uses. I thought at first that he was not serious, but he was more, he was determined not to spend the money of the League on Parliamentary contests. This was Davitt’s view, and Brennan and Egan concurred. “But,” I said, “you are surely not going to allow foes to take up all the high places just for the fun of pulling them down? You can make a revolutionary use of the Parliamentary machine as well as every other political weapon. Get your men elected and don’t let them go to England. Keep them at home and start legislation on your own account.” But it was no use. Mr. Davitt and the advanced men were firm and a week was lost which left very hurried and hot work afterwards. The following Sunday, Mr. Parnell and Mr. O’Kelly went to a League meeting at Enniscorthy where the platform was attacked by a powerful body of extreme men, inspired by Father Joe Murphy and O’Clery.[7] Among other casualties, Mr. Parnell got his trousers torn from the boot to the hip. He stitched it roughly and wore it during the Election campaign. O’Clerys bludgeon men were more convincing than my arguments, for Mr. Davitt lent Mr. Parnell £1,000 to fight the Elections. I stopped away at my farming during the drifting week, but when I got Monday’s paper I drove to Dublin in haste and met Mr. Davitt and Lysaght Finegan[8] in O’Connell Street. “Well,” I said to Mr. Davitt, “what now?” He rejoined: “I have advanced money on loan to fight the Elections. He is over in Morrison’s[9] and he wants to see you.” “All right,” I said. “Where is Finegan going?” “I am going to Ennis,” he says. I asked: “Are you going to win?” “Well,” he says, “if we don’t win we’ll burn the town.” Of course he did win. When I got to Morrison’s I found Parnell and Judge Little in conference. When the judge saw me he exclaimed: “Here is the man for Kildare!” “No,” says Parnell, “Kettle helped to get us into the trouble and now he seems not to care how we get out.” “Now,” I said, “you know that is not true. How much better would the position be if I had my way a week ago.” “Oh, I admit you were right then, but what are you going to do now?” “Anything you want me to do.” “Well, will you come to Kildare?” “Yes. Kildare or any other place you can order me until the Election is over.”

We went to Kildare on a midday train, and had a rare scene with Alderman Harris[10] in the carriage going down. The Alderman was one of the candidates for Kildare, and he begged and prayed Mr. Parnell to get him adopted with a fanatical fervour I shall never forget. When we got to Athy, which was the nomination place, we found that Father Farrelly and young Kavanagh had a candidate ready in the person of Mr. James Leahy[11] who represented it for years afterwards. Mr. Parnell turned to me and said: “This fat man will be no use. He will fall asleep in the house. I must propose you.” I never meant to go to Parliament if I could help it, and said: “He will do very well. You may want me somewhere else.” He was not half satisfied, and he cross-examined Mr. Leahy as to how he would be able to attend and sit up at night, but the candidate said “Yes” to everything. So, as his friends were insistent, he had to take him. Father Nolan of Kildare Town was holding a Harris Meldon meeting at the Market House when he came out, but Mike Boyton[12] moved somebody else to another chair and started a Leahy meeting on the same platform, so after a little Father Nolan said he would not play second fiddle to anyone, so he bid us good-bye and left. When the meeting in Athy was over there were three candidates from Carlow with cars waiting to get Mr. Parnell to go to Carlow and ask them to retire. There were four altogether, but as there was only one required they wanted to make a merit of necessity and retire at Mr. Parnell’s request. We drove to Carlow by a good road on a beautiful evening and there was an Election meeting held at night at the College, at which Mr. Charles Dawson[13] of Dublin and Limerick was adopted for the Borough seat. Father Kavanagh,[14] a great admirer of Parnell, presided. The two county seats were managed by the people of Carlow without reference to Parnell and E. Dwyer Gray[15] and McFarline[16] were returned as Independents. After dining with the retired candidates, of whom Count Plunkett[17] was one, Mr. Parnell and I started late at night for Co. Wicklow to be present in Rathdrum at the selection of candidates next day. We stopped at Tullow and got about three hours’ sleep, and started in the grey of the morning to Woodenbridge to catch the early train to Rathdrum. I learned on that occasion a good deal about Mr. Parnell’s experience as a farmer and cattleman. He had done a good deal in the stock line but not much in tillage. One of his comments was that anyone could sell cattle but that it takes a good judge to buy them right. On the run down to Rathdrum I got my first view of Avondale.[18] It looked from the railway carriage more remote and romantic, like something standing apart, than I ever thought it did afterwards viewed from any other point. We did not go near it that day, but visited Father Carberry and kept moving about Rathdrum (it was a Fair day) from Dr. O’Dwyer’s to, I think, a Mrs. Comerford’s.[19] We had a band and held two or more meetings. The meeting of the clergy was rather late and protracted, but Parnell hung around although I was tired and sick. But as usual he was right. Only he was about his men would not have been adopted. Corbett[20] and a stranger named McKoan[21] were his men, but they later had to fight a Mr. O’Mahony[22] I think and won only by four votes. We held a meeting in the evening in the town of Wicklow at which I first met Mr. Corbett. On our way to Dublin we travelled with Mr. Toomey, the chief Conservative Election agent for Wicklow and an old acquaintance of Mr. Parnell’s. He was the man whom Mr. Parnell had removed from the Court House when he was High Sheriff of Wicklow. I never listened to a more interesting discussion on politics between two men, Toomey bantering Parnell for leaving the landlord’s lines and ridiculing the new order and the new men, Parnell defending and striking back all round. On our way from the railway to Morrison’s Mr. Parnell pressed me to tell him seriously who had the best of the bout.

Parnell had to attend a meeting at Navan the next day where he got a great ovation from his own constituents, so I got a day off for my farming. When I got to Morrison’s the following morning, he was at breakfast with Arthur O’Connor[23] whom I met for the first time. He told us about the great meeting at Navan, but I was after reading about a meeting at Cork where the clergy, led by Dean Neville,[24] made a bad attack on the new Party. I asked him if he read the report. “No,” he said, “What did they do?” “Well,” I said, “they denounced you and all your works, and someone has nominated you for the City so you will have to go to Cork.” “I cannot go,” he says. I have to go to Maryborough[25] with O’Connor, and Wicklow will be lost unless I visit Baltinglass.” Well, I handed him the newspaper and he read a little of the report, when he exclaimed, “Those priests, will they never keep quiet!” This was the only positive reflection in words I ever heard him utter about the clergy.[26] After a little thinking he says, “Yes, I must go to Cork. I tell you what I’ll do. I will go and fight the City and you must fight the County.” I said, “The County is settled. Shaw[27] and Colthurst[28] have been adopted by the Farmers Club, and all the leading men are pledged to support them. Shaw was pledged to seek a commercial seat in the City if the farmers decided to start a man of their own. Last week they wanted £400 or a man, but they got neither. So the county is settled.”

We went to Maryborough and got Arthur O’Connor started for the Queen’s County.[29] During the lunch after the public meeting a wire was handed to Parnell, when he stood up sharply and waving the telegram called for a cheer for Ennis and Finegan. So Clare was still the Banner County.[30]

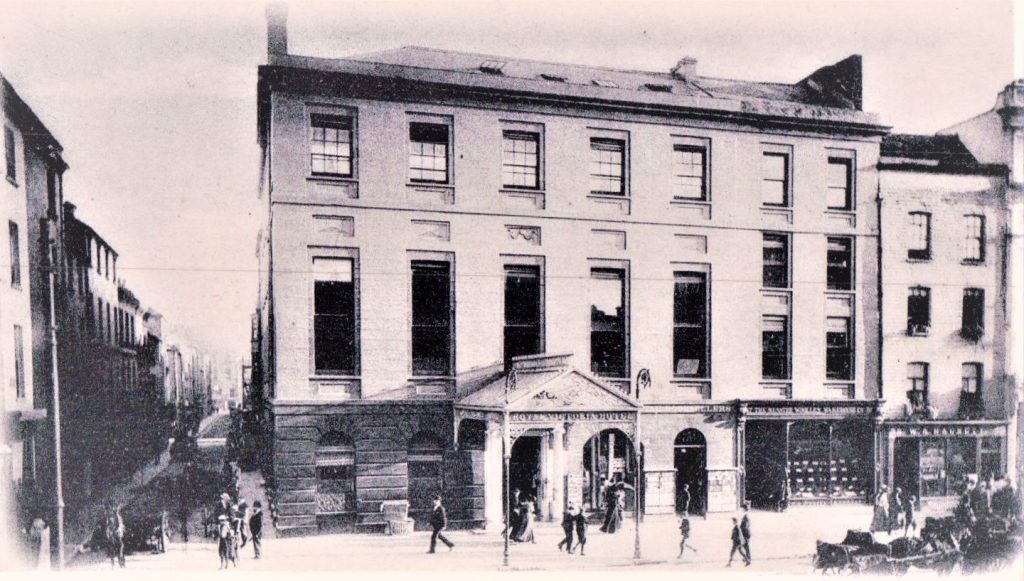

Mr. Parnell and I started for Cork by the night mail and got there very late, but late and all we were joined at Blarney, I think, by Mr. Riordan, President of the Cork Farmers Club, and some others. They were delighted that Parnell was going to fight the City, but they were shocked at the notion of upsetting the arrangements in the County. In fact they would not hear of it. They told him that if he had sent them a man or £300 the week before they could carry the County but now “we are all pledged to Shaw and Colthurst and we cannot go back on our promise.” He did not push the matter any further, but the very mention of a County contest had a very bad effect on the fight in the City. We arrived in Cork on Friday night and next morning some of the prominent City men called on Parnell, to explain how the matter stood. There were four nominations: Daly, Home Ruler[31]; Murphy, Clerical Whig[32]; Goulding, Conservative[33]; and Parnell. At the beginning there was complete mystery about Parnell’s nomination. The Cork men thought Parnell got himself nominated, and Parnell thought the Nationalists had him nominated, and would consequently have arrangements made for the fight. But instead of that we found all Cork at sixes and sevens about the whole business. We learned a little later in the day on Saturday that it was the Conservatives who advanced the nomination money to an enterprising nephew of Dan Riordan’s, to start Mr. Parnell to break the Whig Murphyite Party and give their man a chance.[34] They did not expect that Parnell would turn up in person. There was nothing but doubt and misgivings and distrust expressed by about six sets of deputationists who called on Parnell. No one seemed to have the least idea of what should be done, and no one volunteered to do anything until some time in the afternoon a little man with bright eyes, Alderman O’Dwyer, I believe it was, called by himself and said, “Mr. Parnell, you have got to fight this election. No one in Cork seems to be in a position to help you. Just take my advice and make your own arrangements and hold a meeting this evening in some prominent or populous place in the City, and another tonight here in the hotel, and a meeting in the Park tomorrow.” Monday was the polling day. This advice was at once put into operation by a very able solicitor, Mr. Horgan, who was appointed Parnell’s agent, and one only priest, Father O’Mahony, C.C., and I think Tim Healy came on the scene some time on Saturday. There was a small attendance at the evening meeting. There was a great crowd in the street opposite the Victoria Hotel[35] at night, but all the City seemed to be in the Park on Sunday. It was a beautiful, sunny, calm evening, and only on that and on one other occasion did I ever see Parnell put forth what appeared to be his full powers. He elected to speak from the driving seat of a very high brake where he stood alone. He spoke like a man inspired, and his measured and deliberate but passionate tones rang out to the most distant of the 15,000 or 20,000 people in Cork Park. That speech secured his return, but only to second place, as the public mind of Cork was in a terrible state of confusion as to what was right or wrong just then.[36]

For all the confusion in the City Mr. Parnell did not give up the notion of fighting in the County. He secured the services of one of the best men in Cork to get a nomination paper filled but so complicated was the case that it took John Heffernan of Blarney four hours going round the markets on Monday morning to get eight men who were not pledged to Shaw and Colthurst. When he got the paper which had to be lodged the same day I fought strongly against standing under the circumstances. Quite a scene took place at my resistance in the presence of Edmund Farrell of Queenstown[37] and Tim Healy. I asked and pressed Mr. Farrell to stand and Mr. Parnell said, “Yes, Mr. Farrell or any suitable man would do.” Farrell refused, and Mr. Parnell laid his hand on my arm with such force that I turned sharply round and met his gaze. His next words were spoken in a low tone and were, “Will you let me have my way this time.” “Yes,” I said, “and the responsibility.”[38] My name was put on the paper, but I was so dissatisfied that I turned up at the nomination place only at the very last moment. It was upstairs in a building that was being repaired and it was difficult to get to the stairs, but Mr. Parnell was there and he took me by the arm and literally carried me up just as the clock stood at the last minute of the time. He arranged about the fight in the County and I pretended I had to go to Dublin. So we both travelled in a sleeping saloon where I got such a cold as prevented me from speaking much during the contest. He went on to Leitrim or some place he was expected next day, Tuesday. The only man available to come with me to Cork was F. H. O’Donnell. He came to the Imperial Hotel[39] in Dublin and was to have joined me at Kingsbridge[40] on Thursday, but when he saw the joint manifesto of the four bishops who exercised spiritual jurisdiction over Cork County, denouncing my candidature, he declined to enter on such a contest. So I had to go alone and I went on to Queenstown, as Mr. Farrell was the only Tenant Right man in the County who was free to fight. I asked for an interview with the Bishop, but he declined to see me. I returned to Cork that night and met enthusiastic supporters of Parnell in the Wilson family who kept the hotel, and Bill Cahill the famous racing man and a lot of able free lances and Fenians. I was joined next day by that gloriously good dashing Irishman, Lysaght Finegan, who was after winning Ennis. I took no part in the arrangements, but I went by myself to a meeting that had been called in the Farmers’ Club headquarters, but when I got to the door I met a lot of leading farmers coming tumbling out, having been ejected by the free lance politicians and Fenians, and so the County contest was fought with the leading men out of action.[41] I visited a few towns with Finegan but did little of the work, but I fell into a position in Macroom where I had to strike out to save my own skin.

We were met at the railway station by four fine-looking clergymen who spoke out at once and called us Garibaldians. I was unlucky enough to have a rug with red stripes on it.[42] It was a fair day, and we decided to go along by the fair green which was in a valley with the road running on a narrow strip of high ground round it. There seemed to be a strong gathering of Colthurst men about as he was holding a meeting later on in the town. The priests and their party who were armed with good sticks followed us, and the crowd was augmented as we went along. When they got us in the narrowest part of the road they called on the people to attack and drive us out of the place. We were hustled off the road very sharply down the green a bit but we decided not to retreat. We got round a cart with a good lamb creel[43] on it, and this we mounted and Finegan shouted for fair play. We both commenced speaking at different sides of the cart round which a great crowd had gathered. The priest addressed the same crowd from the high ground at the road some perches[44] away. After about twenty minutes we got the crowd well under control, Finegan talking all the time, and I putting in an odd shot. We told the people not to assault the priests; not to insult them, but to stand together and to push the priests’ party on before them down the road to their chapels and their prayers. This the people did in jolly good humour, and thus ended what at one moment seemed to be an ugly fix.[45] There is only one other episode worth noting in the Cork election. Finegan and I slept at the New Railway Hotel at Mallow and were out early walking about before breakfast. The head porter came along and asked us did we see the Chief. “The Chief is away in such a place at present,” says Finegan. “Well, you’ll find him in No. 6,” said the porter, “he came in the night.” We bounced into No. 6 and found Parnell wide awake lying on his back and the sun shining on the bed. After the first greeting he says, “Do you know, Kettle, what I have been thinking about for the last few minutes?” “Well, I give it up, so you may as well tell us.” “Why, the land does not belong to the landlords at all.” I answered, “Is it only now you found that out?” “Yes, just within the last hour.” “Why,” I said, “I called them the head stewards of the National Property years before I heard of Davitt or Henry George. In addition, they are unjust stewards who want to confiscate what the people put in and on the land.” “Yes,” he says, “the Irish Land System seems to be bad all through.” A. M. Sullivan wrote a brilliant article on my startling pronouncement.

On the polling day the 250 priests in County Cork turned out and kept watch and ward at all the polling stations. I saw them at the places I visited, and a fine body of men they were, but of course they were politically wrong, and they were all round on my line in about twelve months afterwards. When T. M. Healy’s wire reached me in Dublin announcing that I was beaten by 154 I silently thanked Heaven that I was out of the Parliamentary groove for the time being.

One other matter occurred during the general election that gave Parnell some trouble in after years and threw out another man who had the ability to play many a useful part as a follower of Parnell, but who drifted by being thrown out of the current at this election. Philip Callan[46] was member for Dundalk and a great follower of Mr. Butt’s. He made enemies by his outspoken and aggressive advocacy of that great old man. Some of these enemies urged Parnell to favour Charles Russell’s candidature against Callan. I had great opportunities through the Tenant Right organisation of getting authentic information on many things throughout Ireland. I advised Mr. Parnell to let Callan alone. “You may put him out of Dundalk, but if you do, he will be returned for Louth in spite of you.” In the midst of the Cork election in a crowded room he held a telegram up the other side of the room announcing that Callan was returned for Louth.

- Timothy Michael Healy (1855-1931) was an agrarian nationalist politician, journalist, author, and barrister who was returned as MP for Wexford in 1881 and attained parliamentary prominence with a reputation as an extraordinary speaker. Although an accomplished publicist of Parnellism, there was some mistrust between Healy and Parnell and he sided against Parnell during the later split. He influenced the political direction of Irish nationalism to an agrarianism of the right and his political career continued into the 1920s, when he became the first Governor-General of the Irish Free State (DIB 2009, ‘Healy, Timothy Michael’). ↵

- Parnell had travelled to the United States in December 1879 in order to obtain financial support for the new movement. While there he spoke in 62 cities to largely Irish-American audiences, met with President Rutherford B. Hayes, and on 2 February 1880 he addressed the US House of Representatives. This trip ended abruptly when he was in Montreal with Dillon and Healy and they learned that Parliament had been dissolved and new elections were to be held in April 1880. Parnell and Healy hurried back, only reaching Ireland in mid-campaign and the party had to work vigorously to secure candidates allied to Parnell (Bew 2007, 316-17). ↵

- Joseph Gillis Biggar (1828-90) was an Irish nationalist politician from Belfast. Born into a Presbyterian family, he later converted to Catholicism. He served as an MP as a member of the Home Rule League and later the Irish Parliamentary Party from 1874 to 1890. He was a popular figure in Ireland and well-known for turning obstruction of Parliament into an art form by reading official documents for hours to delay business. Although a close friend of Healy, he was not an intimate of Parnell (DIB 2009, ‘Biggar, Joseph Gillis’). ↵

- James Joseph O’Kelly (1845-1916) was an Irish nationalist journalist, politician, and MP representing Roscommon as a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party from 1880 to 1916. When the party split in 1890 over Parnell’s leadership, O’Kelly supported Parnell (DIB 2009, ‘O’Kelly, James Joseph’). ↵

- James F. Grehan (1836-96) of Lehaunstown, Cabinteely, Co. Dublin, was a friend of Davitt, a member of the Land League committee, and a prominent farmer in Cabinteely (King 2009; WikiTree n.d.; Clancy 1889, 148). ↵

- The trip to the United States raised £70,000 for the cause. ↵

- Patrick Keyes O’Clery (1849-1913) was a barrister and Home Rule MP for Co. Wexford from 1874 to 1880. In the 1880 election, although backed by the Catholic clergy, he was defeated by the Parnellite candidate. The outbreak of violence at this meeting in Enniscorthy on Easter Sunday (28 March 1880) resulted in Parnell being attacked and injured. In 1903, he was created a count by Pope Leo XIII (Wikipedia 2023, ‘Keyes O'Clery’). ↵

- James Lysaght Finegan (1844-1900) was an Irish barrister, soldier, merchant, and politician who supported the nationalist cause. He served as an MP from 1879 to 1882. He was regarded as anti-clericalist due to his open acknowledgment of close contact with the French anti-clerical Henri Rochefort – a fact that would have contributed to clashes with bishops and clergy in Ireland (Lyons 1977). ↵

- Morrison’s Hotel on Dawson Street in central Dublin was a base for Parnell and his lieutenants and was where he conducted much of his political business in Ireland. ↵

- Matthew Harris (1825-90) was a self-educated agrarian activist. He had strongly supported the Repeal and Young Ireland movements and was known as an enthusiastic democrat and nationalist. He was a leading figure in the IRB as the representative for Connaught. He helped to establish the Mayo Land League in 1879 and played a leading role in establishing branches of the League across the west of Ireland. He was elected MP for Galway East from 1885 to 1890 (DIB 2009, ‘Harris, Matthew’). ↵

- James Leahy (1822-96) was a tenant farmer and nationalist politician who was a MP for constituencies in Co. Kildare from 1880 to 1892 (Wikipedia 2022, ‘James Leahy’). ↵

- Michael P. Boyton (1846-1906) was one of the official Land League organizers. Born in Kildare, he emigrated to the United States with his family as a child. Boyton returned to Ireland in 1879 and joined the Land League. He was arrested with the other organizers and sent to Kilmainham Jail in 1881, but was then released after claiming American citizenship. He subsequently spent time in England before moving to South Africa (Ancestry.com n.d., ‘Michael Peter Boyton, 1846-1906’; Kee 1993, pp. 268, 395). ↵

- Charles Dawson (1842-1917) was a Home Rule MP for Carlow from 1880 to 1884, and he often spoke at Land League and National League meetings around the country. He also became lord mayor of Dublin (1882-83), which reinforced his prominence within the Irish Parliamentary Party and allowed him to use that office as a platform for his nationalist politics (DIB 2009, ‘Dawson, Charles’). ↵

- James Blake Kavanagh (1822-86) was a priest, a nationalist, and a philosophical and scientific writer who, as a member of the Land League, acted as an intermediary between landlords and tenants. He died while saying mass in October 1886 in his parish church when a marble figure of an angel fell from the canopy above the altar (which he himself had designed) and struck him, causing him to fall and strike his head fatally on the alter steps (DIB 2009, ‘Kavanagh, James Blake’). ↵

- Edmund Dwyer Gray (1845-88) was born in Dublin. He was the son of the proprietor of the Freeman’s Journal, Sir John Gray, whom he succeeded in this role in 1875. A convert to Catholicism, Gray became a Dublin city councillor (1875-83), and a Home Rule MP for Tipperary (1877-80), Carlow (1880-85), and St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin (1885-88). A moderate, he was one of eighteen MPs who voted against Parnell’s leadership of the party but subsequently supported him. Under his management, the circulation of the Freeman’s Journal increased and it became highly profitable (DIB 2009, ‘Gray, Edmund William Dwyer’). ↵

- Donald Horne Macfarlane (1830-1904) was a Scottish merchant who served as a Home Rule Member of Parliament for Carlow from 1880 to 1885. He subsequently served several times as a Crofters Party MP for a constituency in Scotland between 1886 and 1895 (Wikipedia 2022, ‘Donald Horne Macfarlane’). ↵

- George Noble Plunkett (1851-1948) was a nationalist politician, scholar, and museum director. In 1884, he was created a Papal Count by the Pope. Despite his close assocation with the Church, he supported Parnell against the Catholic hierarchy in 1890. He was a Member of Parliment from 1917 to 1922 and a Teachta Dála (TD) from 1918 to 1927. He was the minister for fine arts and the minister for foreign affairs in the Irish government between 1919 and 1922 (DIB 2009, ‘Plunkett, Count George Noble’). ↵

- Avondale had been described as a ‘square, very ordinary-looking building’ but was placed in beautiful surroundings close to the Vale of Avoca (Bew 1980, 6). ↵

- Philip Carberry (1833-1902) was the parish priest of Rathdrum, Co. Wicklow, and a supporter of Parnell, whose home, Avondale, was in his parish (Ancestry.com n.d., ‘Fr. Philip Carberry’). Medical and professional directories of the time list a Dr. Michael C. Dwyer with an office in Rathdrum. Eva Mary Comerford (1860-1949) was the wife of James Charles Comerford (1842-1907) of Ardavon House, Rathdrum, Co. Wicklow, the owner of Rathdrum Mill and a friend of Charles Stewart Parnell (Comerford 2016). ↵

- William Joseph Corbet (1824-1909) was a civil servant and Home Rule MP for constituencies in County Wicklow from 1880 to 1892 and 1895 to 1900. He was a close political colleague of Parnell and he organized the care of Parnell’s farm at Avondale during his detention for Land League activities (DIB 2009, ‘Corbet, William Joseph’). ↵

- James Carlile McCoan (1829-1904) was barrister, journalist, and author who was elected as a Home Rule MP for Wicklow in 1880. He had a falling out with his colleagues in Parliament and served out the term as a Liberal independent (DIB 2009, ‘McCoan, James Carlile’). ↵

- David Mahony was the (unsuccessful) Liberal candidate in the 1880 general election for the Wicklow seat (Wikipedia 2023, ‘Wicklow (UK Parliament constituency)’). ↵

- Arthur O’Connor (1844-1923) was an Irish nationalist politician and Member of Parliament from 1880 to 1900. He was a member of the anti-Parnellite group from 1892 (Wikipedia 2022, ‘Arthur O’Connor (politician, born 1844)’). ↵

- Henry F. Neville (1822-89) was a Catholic parish priest and dean of the Cork diocese. He opposed Parnell when he stood (successfully) in the city constituency in the parliamentary elections in March-April 1880 (DIB 2009, ‘Neville, Henry F.’). ↵

- The name of Portlaoise, County Laois, from 1557 to 1929. ↵

- During this campaign the Church was to be one of the most formidable of Parnell’s opponents. If the clergy had been able to come to a consensus, this may have decided the outcome. However, the bishops could not always be sure of their own clergy and even within the Church hierarchy there were differences of opinion which made united action difficult. Some clergy believed that Parnell ‘raised hopes in the minds of his hearers that could never be realized’ and awoke ‘a spirit of discontent’ (Lyons 1977, 111). ↵

- William Shaw (1823-95) was an Irish Protestant nationalist politician and one of the founders of the Home Rule movement. He held his seat at the 1880 election but lost an election for the party chairmanship to Parnell (Falkiner & O’Day 2004). ↵

- David la Touche Colthurst (1828-1907) was a Home Rule League politician who was elected MP for Co. Cork between 1879 and 1885 (Wikipedia 2022, ‘David la Touche Colthurst’). ↵

- The name for Co. Laois until 1922. ↵

- The election lasted for most of April 1880, during which Parnell continued to campaign while vigorously ‘selecting candidates, speaking in their favour, defending his House of Commons record, propagating the doctrines of the League, and circulating dizzily between [the] three constituencies [of] Cork city, Meath and Mayo’ (Lyons 1977, 110). ↵

- John Daly (1834-88) was a moderate Home Ruler (Wikipedia 2021, ‘John Daly (Irish Member of Parliament)’). ↵

- Nicholas Daniel Murphy (1811-89) entered politics as a Liberal candidate for Cork city in 1865. Although his family had a tradition of nationalism, Murphy was an old-style Whig who favoured the union and insisted that Home Rule did not mean separation but federation within the empire (DIB 2009, ‘Murphy, Nicholas Daniel’). ↵

- William Goulding (1817-84) was a successful businessman and conservative Tory politician, winning a seat in 1876 as the first conservative elected in Cork city for 30 years until he lost to Parnell in the 1880 election (DIB 2009, ‘Goulding, William’). ↵

- It transpired that the Tory camp had paid him £250 to nominate an ‘extreme’ candidate, with the intent of splitting up the nationalist vote and getting the Tory William Goulding in. On discovery of this the remaining £200 was reluctantly handed over and used to cover Parnell’s election expenses (Lyons 1977, 110). ↵

- The Royal Victoria Hotel was located on the corner of St Patrick’s Street and Cook Street in the center of Cork (McCarthy n.d.). ↵

- Parnell was to hold his seat in Cork for the rest of his career. ↵

- Cobh, known from 1849 until 1920 as Queenstown, is located on the south coast of County Cork. ↵

- Kettle was acutely aware that the local Tenant Right movement had already prepared their own candidates for the election. In addition, his association with Parnell had antagonised the Catholic hierarchy in Munster and the election campaigning had created the persistent impression that Kettle was anti-clerical in politics, which resulted in the clergy issuing a condemnation of his candidacy (DIB 2009, ‘Kettle, Andrew Joseph’). ↵

- The Imperial Hotel was a hotel in Dublin’s principal thoroughfare, Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street). ↵

- Kingsbridge Station is the original name of Heuston Station, one of Dublin’s largest railway stations. ↵

- An ejection of the leading farmer class would have affected his potential support base and Kettle was eventually defeated by 151 votes (DIB 2009, ‘Kettle, Andrew Joseph’). ↵

- This was in reference to Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-82), the popular Italian revolutionary, who was intensely anti-Catholic and anti-papal. His followers, the garibaldini, wore grey woollen trousers with a red stripe (Parks 2021). ↵

- A large, strong wicker basket. ↵

- A perch is a distance of several metres. ↵

- Kettle’s recollections demonstrate how elections in this period could be bitterly fought and sometimes potentially violent, and that the mood of a crowd could be volatile and easily influenced by the personalities involved and their oratory skills. ↵

- Philip Callan (1837-1902) was a Liberal Home Rule politician and lawyer. He was an MP (for Dundalk and then Louth) from 1868 to 1885. He was a follower of and adviser to Isaac Butt and was prominent in Butt’s Home Government Association. He was not a supporter of the Land League and chafed under the leadership of Parnell, whose opposition led to Callan losing his seat in Parliament in 1885 (DIB 2009, ‘Callan, Philip’). ↵