Chapter 8: The Arrest of Parnell and the No Rent Manifesto

Mr. Parnell attended a League meeting the next day and announced the enlarged programme, taking in the labourers and almost threatening the farmers. Also he started the project of taking the largest house in Rutland Square[1] for the Industrial Bureau, and when he went to Cork a few days afterwards he let himself loose on the boycotting of British manufacturers. William O’Brien in his fascinating but surface view of this period attempts to glorify everyone about the Tyrone election. It was the exultation of the British press and people over his defeat in Tyrone that drove Mr. Parnell to exhibit his power over every other part of Ireland. It was his declared determination to test, and, if necessary of course, block the working of the Government rent-fixing Land Act, and his call on the people at Cork to boycott British manufacturers that moved every section of Gladstone’s Cabinet to agree upon his arrest, and upon the suppression of the Land League.[2] Mr. Parnell during those few weeks was leading the movement in Ireland on revolutionary lines, perhaps without being fully aware of it, to make up somewhat for the failure to do some months before, and the people simply went wild with delight.[3] The result was the same – imprisonment – but the sequel was very different. The February sacrifice, according to Gray and Parnell himself many times afterwards, would have settled the land question and have forced all classes together on the national question, but the October sacrifice led to the tragedies that followed and settled nothing.

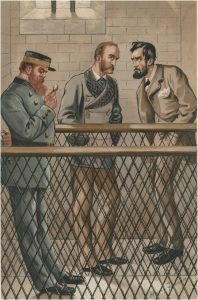

Brennan and I were talking in the yard when our attendant told us that Mr. Parnell was arrested. We asked him how did he know. “Why,” he says, “he is in Boyton’s room.” I walked in like a man in a dream. Strange how I never expected his arrest. I wanted everyone else arrested, but not him. He was sitting on the side of Boyton’s bed when we took a good look at each other. “Well, Kettle,” he says, “see where you have landed me now. If you left me at home at Avondale minding my own business I would have escaped this.” “Never mind,” I said, “it might be worse.” We got talking together soon afterwards and I said: “This is simply horrible. How are you going to get out unless you sneak out?” “I expect,” he says, “we will have plenty of time to discuss the going out. Tell me something about how you spend your time here.” I gave him a sketch of our easy, lazy prison procedure, and amongst other things he asked me had we devotions on Sunday. I said: “Yes. We have Mass at nine o’clock and a sermon.” “Well,” he says, “I will go to Mass next Sunday with you.” I said: “I am delighted to hear it although somehow I am not surprised. I had,” I said, “a very serious conversation with poor Butt a short time before he died, and he seemed to have a decided leaning towards the Catholic religion.” “Yes,” he says, “I believe the Catholic religion is the only spiritual religion in the world. It seems to connect the world and the next in a more positive way than the doctrines of any other Church.”[4] When I had to go to my own quarters I said: “Now don’t forget about Sunday.” But unfortunately before Sunday came the place was packed with all the leaders, and it was on the Sunday next that William O’Brien produced and we signed the No Rent Manifesto.[5] O’Kelly was the only one who at once realised like myself that Parnell was floored, for the present at least. O’Kelly said: “You may as well make terms and go out as soon as you can, as you can never get out any other way.” But O’Kelly was laughed at for his expression of cowardly common sense, as Parnell called O’Kelly’s way of looking at things many years after. Brennan and myself looked like dancing round the yard when he heard that O’Kelly and Sexton and the “Paris Paper” House of Commons men were caged.[6] I had a great opportunity of travelling over the minds of all sorts of men in Kilmainham, and I enjoyed it immensely. The only impossible men I met there with whom I could never compare notes were William O’Brien and a sombre Fenian from the West named Walsh. It was impossible to say anything that would please Walsh, and when O’Brien would be done rushing or gushing you would not have time to say anything. Dwyer Gray and Parnell were the two best listeners I met, and O’Brien is by long odds the worst. He never gives himself a chance to learn anything to change his first impressions. If they happen to be right he will drive them home with tremendous force, but if they are mistaken, his state is hopeless.

The No Rent Manifesto was, of course, my lever in February to lift landlordism off the necks of the people and to justify Gladstone in adopting the Land League purchase programme for the settlement of the Irish land question. Gray said that with the Parliamentary Party in prison Gladstone could propose any kind of settlement and that the proposal to bring in six years’ purchase of the rental to bridge the difference between what the tenant could pay and the landlords could sell at would induce the landlords to help on the settlement. Gray was to take charge of the question in the House in the absence of the Party. He was not a member of the Party and, as he said, was not going to jail. When the question came up in Kilmainham while O’Brien was labouring to persuade Dillon to sign the manifesto, I had a few earnest words with Parnell. I said: “This is a very serious thing to now ask the people to do what very many honest men cannot do. When I proposed this I had a definite object in view, namely a six months’ fight and a definite land settlement. Now when Parliament has dealt with the land question without settling it, and when the people have neither the leaders nor the organisation, they are called upon to start on an indefinite warfare which I know in many cases they can’t wage successfully, and this is to go on until they succeed in beating the British Government. I shall never taunt you, Mr. Parnell, even in private, but I must ask you not to blame the people if they fail to carry out this policy now to the extent that was feasible for the six months’ effort. But,” I said, “I suppose there is nothing else to be done and we must strike back.” I remember well that it took O’Brien all he knew to induce John Dillon to sign it, but he succeeded, perhaps for the same underlying reason that something had to be done. When Mr. Parnell had signed it, he left down the pen and straightened himself and looked at me. I signed it in silence, and never explained my real view of the matter until now.[7]

I was only about seven weeks in Kilmainham with Mr. Parnell, and while there we had no particular intercourse. He knew that I was perhaps the most disappointed man in Ireland, and we had nothing but failure to talk about. We settled the labourers’ question one day at exercise, or rather the lines upon which it could be settled with houses and land, and worked by the Boards of Guardians, the details to be left to circumstances. We dined together every day, and Mr. O’Brien in his recollections gives, I think, a very fair sketch of the prison life after he came there.[8] The old Kilmainham Party consisted of Dillon, Brennan, Boyton, Father Sheehy, and myself in the medical department, with many visits from John O’Connor, John Clancy, Paddy Murphy, and a few others, but we could and did visit all the exercise grounds, and on the whole, spent a very pleasant time as prisoners. Notwithstanding the unremitting attention and skill of the genial, manly, high-spirited, self-sacrificing Dr. Joe Kenny, I lost my health. Curious how all the sedentary city and towns fellows felt Kilmainham as a holiday, but the robust, open-air, country people generally went physically wrong. My wife’s health got even worse than my own with the worry of the business and anxiety of looking after a large family, and she was held to be in a bad way. Still she came every week to see me, and on one occasion she brought me a most pathetic account of poor Mrs. O’Brien, William’s dying mother.[9] Forster sent a couple of specialists to see me early in December, and before the end of the month I was examined by Dr. Carte,[10] the decent prison doctor, at the request of Dr. Kenny, and I was liberated on his report about Christmas. The order came late in the evening and the Party were assembled in Parnell’s room and when I was saying good-bye Parnell held my hand a little, saying: “I am very glad you are going out, Kettle. If you remained here much longer you would lose your health permanently. I shall always regret not having taken your advice last February. Had we done so the fight would have been over now, and over better than it ever can be.”[11] “No use,” I said, “crying over spilled milk. What am I to do when I go out? I know a friendly rate collector I could kick up a row with, and strike against taxes as well as rent.” “No,” he says, “do nothing until you hear from us. Go away and recruit your health somewhere, and if we want anything done we will let you know.” “Well,” I said, “anything in the way of extreme action outside will react on you here, so I shall let you make the running this time and wait for your orders absolutely.” I got no orders, and I took no part in the work outside. I went to London and to Paris to visit Egan and all our friends all over the place. We had a couple of sheriff’s sales about rent, but the landlords got their rent and the lawyers their costs, for unless we burned the place we could not prevent them as we always had rolling stock to double the value of the rent lying about that could not be dispensed with unless we threw a large number of people idle and allowed the landlords to punish everyone and to get their rent into the bargain. This was some of the difficulty I warned Mr. Parnell about before signing the No Rent agreement.

It was Mr. Chamberlain[12] who negotiated Mr. Parnell’s release from Kilmainham, and who got Gladstone to throw over Forster.[13] As the leader and mouthpiece of the English Radicals he seemed to contemplate a junction of Irish democracy under Parnell and his own Radical following in Great Britain to bring him to the Premiership. It was notorious that it was his association with the Irish Party of Action, Parnell and O’Donnell, that induced Gladstone to include him and the Republican preacher, Sir Charles Dilke,[14] in his Cabinet. I believe that the Page-Woods (Mrs. O’Shea) and the Chamberlains were on very intimate terms socially, and I expect that Mrs. O’Shea wanted Parnell liberated.[15] It seemed a likely enough consideration on Chamberlain’s part if he could have used Parnell and his great democratic forces for his own purposes that he would be willing to concede Ireland’s demands if it did not tend to break up the alliance. Of course, Parnell’s was purely and necessarily a democratic and not an Irish national movement, and his lieutenants and “items,” as Biggar called them, were all labour men of one kind or another. But Parnell was not a democrat. He generally held very different views from the men around him. Still he seemed never to forget the value of every man who joined him in the struggle.[16]

- This is now Parnell Square in Dublin. ↵

- Kettle was probably correct in his view of the contribution of the Tyrone defeat to the subsequent arrest of Parnell. However, to allay the fears of the left, Parnell had decided on the face-saving formula that the act was to be ‘tested’ and he attended several large Land League demonstrations in opposition to it. His failure or reluctance to wind down agitation and the resulting open confrontation with Gladstone finally led to his arrest on 13 October 1881. As Bew notes, although he probably did not deliberately seek arrest, it may have been welcome to him when it came. He wrote to Mrs. O’Shea that day: ‘Politically it is a fortunate thing for me that I have been arrested, as the movement is breaking fast, and all will be quiet in a few months, when I shall be released’ (Bew 2011, 82-86; Comerford 1996a, 48). ↵

- While some saw the 1881 Land Act as a substantial gain, up to 20 per cent of the smaller and poorer farmers (over 100,000 of them) remained too deeply in arrears to clear their debts and take advantage of the new system. They, along with many Land League activists, had supported continued agitation. Violence continued to increase (there were 22 agrarian murders recorded in 1881 alone) and the government held that Parnell and his associates supported these actions (Comerford 1996a, 47; O’Brien 1976, 19). ↵

- Bew explains this casual comment to Kettle as indicative of Parnell’s own lack of serious religiosity and also as an explanation for his lack of empathy with the religious element that existed in Ulster unionism (Bew 2011, 195-96). ↵

- During his imprisonment, O’Brien drafted the famous No Rent Manifesto. It outlined a scheme for the withholding of rent until the government abandoned its policy of coercion, which resulted in an escalation of the conflict between the Land League and Gladstone’s government. After the land bill had become law the tenants, urged on by their clergy, had flocked to the courts to have their rents fixed. It was perhaps unrealistic to expect hard-pressed tenants to turn their backs on legislation which went a long way towards conceding to their basic demands. The No Rent Manifesto further weakened clerical support for the League and was also repudiated by the Freeman’s Journal and The Nation (Bew 2007, 329; Comerford 1996a, 48; O’Brien 1976, 19). ↵

- Kettle had previously had wrangles with the querulous Sexton during the meeting of the Land League executive in Paris in 1880, when he had accused Sexton’s oration in the House of Commons as being one of the greatest obstacles to Irish freedom. ↵

- Kettle’s disappointment in signing the manifesto was well founded. As Bew notes, ‘the apparent radicalisation of the “no rent” manifesto was, in effect, an organised retreat from an unsustainable policy. “No rent” was never designed to succeed, it was designed to create a context in which Land League failures could be blamed on government repression; not bad leadership or flawed tactics, still less the nature of the Irish agrarian movement itself’ (Bew 2011, 90). The movement was on the verge of collapse and as Parnell’s sister Anna Parnell claimed, the No Rent Manifesto was the ‘only cover under which they could withdraw from the impossible position they had created for themselves, and at the same time keep up some semblance of a continuous policy’ (Hearne 1986, 104). ↵

- Among William O’Brien’s writings are his autobiographical volumes Recollections (1905) and Evening Memories (1920). He also published An Olive Branch in Ireland (1910). ↵

- After O’Brien’s father died, he had, at the age of sixteen, become the sole supporter of his mother and three of his siblings. Ten years later (in 1878) he suffered deep personal tragedy when, within a few hours of each other, both of his brothers died from tuberculosis. Three weeks later his only sister also died from the same disease. He later stated in his Recollections how ‘this tragic episode coloured my whole life and character, and explains the recklessness (for it was not calm courage) with which I was afterwards accustomed to encounter personal danger, and which perhaps, alone made me in any degree a formidable element in a semi-revolutionary movement.’ After serving six months of his imprisonment in Kilmainham, he was released on compassionate grounds when, in April 1882, tragedy again struck the family and his mother also died from tuberculosis soon after he reached her side (O’Brien 1976, 2-22). ↵

- Dr. William Carte (1829-99) became the staff surgeon of the Royal Hospital at Kilmainham in 1858 and worked there until his death (WikiTree n.d., ‘William Carte (1829-1899)’). ↵

- Kettle’s recollections here are important as they indicate Parnell’s regret at not following through with the initial rent strike contemplated by the Land League, and pushed for by Kettle, after coercion was introduced in 1881. It seems to confirm his belief that cohesive and prompt action at that time could have forced the hand of the British government to settle the Irish land question more comprehensively. ↵

- Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914) was a businessman, a social reformer, and a radical politician who entered Parliament in 1876. He was a leader of the left wing of the Liberal Party. Chamberlain favoured Irish reform and rejected the use of excessive force in suppressing Irish agitation, but he later opposed Gladstone’s attempts to introduce Home Rule for Ireland (Poole 2022). ↵

- Members of the Liberal Cabinet – in particular, Joseph Chamberlain – had doubts about the effectiveness of continued coercion and internment in Ireland and there had been growing isolation of Chief Secretary Forster and his policy of repression. There was a realisation that the No Rent Manifesto had failed and that the continuing rise in agrarian violence during 1882 was more revolutionary in character and were being committed as a response to coercion (Bew 2007, 331-32). ↵

- Charles Wentworth Dilke (1843-1911) was an English Liberal and Radical politician. A republican in the early 1870s, he later became a leader in the radical challenge to Whig control of the Liberal Party (Jenkins 2008). ↵

- Katharine O’Shea (1846-1921) was the daughter of Sir John Page-Wood. During Parnell’s incarceration in Kilmainham, she gave birth to his child Claude Sophie, but the condition of mother and child was poor. On being released on temporary parole in April 1882, Parnell visited Katharine, who placed the dying infant in his arms (Bew 2011, 92). ↵

- Parnell’s months of incarceration had added an aura of martyrdom to his great popularity, but had also led him to a more moderate path. Meanwhile, the policy of coercion in Ireland was not working and was becoming increasingly distasteful to the Liberal Party. In April 1882, Parnell had indicated to Gladstone that he was eager to make peace with the government. Using Captain O’Shea as an intermediary, a mutual understanding was reached whereby Parnell and his lieutenants would be released, additional relief measures were to be introduced for small tenants in arrears, and Parnell would use his influence to end the disorder in the country and cooperate with the Liberal Party. This so-called ‘Kilmainham Treaty’ led to the resignation of Chief Secretary Forster, who understood that it recognised the Parnellites as the ‘representatives of Ireland’ (Comerford 1996a, 49; Bew 2007, 334). ↵