Unit 2: Understanding How Children Learn

Section 2.1: Introduction

This unit explores the notion of knowledge or knowledges. It discusses the various sources of knowledge, and the varied knowledge ‘holders’, including young children, parents and family as well as ourselves, as informed and reflective early years practitioners. The unit draws on three national frameworks – Síolta, Aistear and the Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Charter and Guidelines, to support your developing ‘image of the child’ as an active, competent learner. Finally, the unit explores the value of shared reflections within communities of practice or learning circles.

Module Learning Outcomes Addressed in this Unit

- Discuss the sociology of childhood as it relates to children’s early learning, constructing the child as an agent and catalyst in their own learning

- Outline the emerging Irish approach to pedagogy and curriculum development, situating this within a contemporary international context

- Discuss the concept of co-constructed knowledge, the role of collaboration with stakeholders and the place and various modes of reflection within this approach

Section 2.2 Learning Outcomes

Upon successful completion of this unit, and the associated activities and readings, you should demonstrate the following unit-level learning outcomes:

- Describe the various sources and forms of knowledge

- Clarify the concept of the child as knowledge producer

- Explain the concept of ‘co-construction of knowledge’

- Discuss the notion of communities of practice and learning circles

Section 2.3 Types of Knowledge

2.3.1 Professional Knowledge

As you come to your practice in the early childhood field, you bring with you a ‘bag of tools’, as it were, that assists you to effectively work with children, families, your colleagues and communities. As a student-practitioner, you will have an array of experiences, working in various early childhood contexts, possibly with children of differing ages and circumstances, from a range of backgrounds, with their own unique stories. Those experiences and the learning that you have engaged with through them, as well as your learning in this programme of study and through other training, have enabled you to develop a set of skills and practices, such as working in a participatory manner, developing anti-bias practice, and reflecting on your practice (Urban et al., 2017). Underpinning your practices and skills, and developed through reflection on your practices, a set of values is at the heart of how and why you work the way that you do. These values may include empathy, privileging children’s rights and respecting diversity, among others (Urban et al., 2017).

The experiences, practices, skills and values that fill this ‘bag of tools’ work in a cyclical way with the knowledge that you hold. Your knowledge has developed through formal learning opportunities, through your experiences, through the trial and error of practice, through the honing of your skills, through reflection. Equally, your knowledge impacts on how you approach your practice, the way you test out your skills, and what concepts and theories underpin your values.

Note: Recall Kolb’s cycle and the notion of transformation through:

- engaging with an experience as a learning opportunity

- reflecting on that experience, drawing on past experiences, knowledge, contexts, culture

- analysing the experience and the reflection, drawing on all of the emerging ideas, underpinned by theory and knowledge, leading to transformation of insight, practice, and perspectives and

- testing the transformed understanding in practice

Urban et al. (2017) focus on knowledge(s), practices and values as the three aspects or dimensions of the professional profile in early childhood professionals. We are encouraged to consider these in the plural – knowledges, rather than singular, limiting perspectives; practices rather than practice, suggesting that due to the varied and diverse contexts in which we work, and roles that we hold, there is ‘always more than one way of understanding (knowing) or acting (professional practice)’ (p. 6). While the kinds of knowledges that inform our practice vary, this knowledge should be related to:

- working with children

- working with families

- working with other professionals and

- understanding our work is situated locally, nationally and globally

![]() Learning Activity 2.1

Learning Activity 2.1

Refer to the following document: Review of Occupational Role Profiles in Ireland in Early Childhood Education and Care (2017) written by Mathias Urban, Sue Robson & Valerie Scacchi. See pages 5-8.

This section sets out the concept of knowledge(s), practices and values as fundamental aspects of your professional early childhood profile. Refer to the table entitled ‘What Kind of Knowledge?’ which lists six knowledge areas. For each of the four related ways of working – working with children, with families, with professionals, working in the local/wider context – link one of these knowledge areas. Consider how each of the knowledge areas informs or supports your work with the linked group or context. Write 100-200 words to outline each.

The report is available at:

Reflective Point 2.1

Considering this notion of knowledges, recall that in Unit 1 we explored how our understanding of the child has evolved over time, how thinking and developments in other areas impacted on the construction of childhood; ideas such as children as rights holders, childhood outside of western contexts, children with agency. Reflect on a perspective that you may have previously held about children or a child or your practice, one that has evolved over time, perhaps as a result of your learning on this course. What new knowledges have you connected with in your development as a practitioner?

2.3.2 Sources of Knowledge(s)

We have outlined how your knowledge develops through a range of experiences, training, reflection, etc. Let’s look further at the sources of the knowledge(s) with which we work. Hordern (2016) suggests the following as some possible sources:

- Tacit knowledge: the inherent sense of what works and what feels right

- Propositional knowledge: certainties or statements of facts

- Knowledge that is contextualised, relating to the social, cultural, or political context in which it is produced

- Research-based knowledge: knowledge that emerges from formal exploration and interrogation, in the lived world of early childhood

- Practice-based knowledge, evolving over time from engagement in early childhood settings

- Traditional knowledge; while this needs to be seen as ‘fallible’ and open to scrutiny, it may still hold valuable ideas and perspectives

It is worthwhile to identify all of these sources of knowledge and many more, and to recognise that we gather knowledge from many sources and in many ways – experientially, through study, or through immersive exposure, through sharing and discussions. However, we must rigorously interrogate the knowledges we are exposed to, in order to ensure their validity. According to Hordern (2016), the validity of the knowledge that is relied upon to inform and make sense of our practices must withstand scrutiny. It must demonstrate value in order to ultimately contribute to a coherent professional knowledge base.

2.3.3 Children as Knowledge Producers

In Unit 1, we explored how our understanding of children has progressed. It is important to ground our discussion of professional knowledge in our practice with young children and their families. Recall that we have moved away from our construction of the child as a blank slate, waiting to be ‘taught’. Nowadays we see the child as having agency and being active in their own learning, truly from birth.

Key Learning Point

The Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Guidelines for Early Childhood Care and Education (DEIG) (DCYA, 2016) present two meaningful concepts that support our appreciation of the young child as a knowledge bearer and creator – ‘funds of knowledge’ and ‘multiple identities’. Aistear (NCCA, 2009; 2015) highlights two other concepts related to children’s learning process: ‘capabilities’ and ‘dispositions’.

Funds of Knowledge

This concept highlights the perspective that the young child is always learning, exploring and experimenting in their own world so that they can make meaning and bring order to that world. Their world includes all the contexts in which they are present and reflects the processes they engage in – the relationships and interactions, the experiences, informed by the unique culture within those contexts. From this perspective, the knowledge young children create does not come about through traditional ‘teaching’ by adults; but rather, is created by the child, for the child, through their experiences (DCYA, 2016). Just as we proposed that practitioners have a ‘bag of tools’ on which to rely, young children create their own ‘funds’ from which the knowledge they have created can be drawn, to support their engagement in new experiences and contexts – the working theories they have developed. It is through this intangible transmission of family practices, values and beliefs, although situated in the wider society, that a culture is reproduced for later generations, adapting to new contexts and ways of living.

Multiple Identities

Just as children are experimenting in their environments and making meaning and knowledge from those experiences, they are also developing a sense of their own identity through these processes. The concept of ‘multiple identities’ highlights to us the complexity and richness of a child’s world and their experiences in it; it supports our understanding of how this variety informs their ‘identity formation’ and how that is based on the many contexts and experiences they have, and the varied capacities they are developing. As the child connects to each context in a dynamic way, to those they have relationships with, building on their experiences, they construct an everevolving image of their self, based on expressed messages and meanings they are exposed to – these can be positive affirming messages that build their esteem; or they can be critical dismissive messages that undermine their sense of self.

Capabilities and Dispositions

Hayes (2013) suggests that cognitive function in young children has two dimensions: capabilities and dispositions. The concept of capabilities is fairly straightforward to understand as it involves the skills and strategies a child demonstrates or employs to support their individual learning. Dispositions, on the other hand, are less easy to define; they have been described as ‘slippery concepts’ (Carr, 2001, in Hayes, 2013), as ‘genuinely hard to pin down’ (Perkins 1993, in Hayes, 2013, p. 43), as they represent intangible abstractions, such as curiosity, motivation, persistence, independence and collaboration, which influence the essence of a child’s engagement with learning and/or their behaviours when involved in learning.

Hayes (2013, p. 50) further discusses two opposing learning characteristics in young children:

Learning Orientation – in which a child is motivated to ‘increase their competence, to understand or master something, to attempt hard tasks and persist despite failure or setback’

and

Performance Orientation – in which a child will avoid challenging tasks for fear of failure and a desire to appear proficient, and will ‘strive to gain favourable judgements from others and avoid negative judgements of their competence’.

To come back to learning dispositions, or ‘habits of mind’ that are developed and demonstrated by children, adults working with young children need to recognise their crucial role in supporting a particular orientation towards learning and the associated ‘positive or generative dispositions’ that will underpin that orientation. Hayes (2013) suggests that the following activities support positive learning dispositions, or a learning orientation, in early childhood settings:

- Encouraging mastery or a learning orientation

- Promoting metacognitive skills

- Developing cognitive and social self-regulation

- Providing for multiple intelligences

- Fostering engaged involvement and emotional well-being

Reflective Point 2.2

Sarah is three years old. She lives with her mother, who is a nurse, and two older brothers in a family home on the farm of her grandparents. Her brother Patrick says he is going to be the farmer when he grows up. Her grandparents have their own smaller cottage. Her father is working abroad so is home one long weekend every month. Sarah’s grandfather is a farmer and she likes to go out with him to the barn to feed the animals. She collects eggs for her granny and likes to cook with her. She chops apples for the Sunday tart. Her daddy’s favourite is apple tart. She and her brother like to climb on the hay bales in the shed but her mother worries about them doing that and can tell them off sometimes. On Monday at preschool, Sarah was excited to tell about the new lambs. It is lambing season and she was up late with her grandfather and brother last night. She explained to her friends that the mother sheep are called ewes and one had three lambs which is too many, so they need to feed it from a bottle. A very small lamb is in the kitchen and Sarah is minding it with her Granny’s help.

Phillip is also three years old. He was born in Ireland but his parents are from the

Philippines. They live together with his aunt and her husband; Phillip has two older sisters but they live back home with his grandmother. They talk on Skype on Sundays after mass and share stories. Going to church is an important part of Phillip’s family’s life. They pray at home before meals and sometimes go to church during the week if there is a special day. Phillip knows about some saints and why they are special; he shares these stories at crèche sometimes. Phillip’s uncle is a good football player. He plays on a local team; Phillip and his dad go to watch him play in games, when his dad isn’t working; his dad has two jobs. Philip likes to play football with his uncle on the green at their house. Lots of the boys in the estate join in and his uncle teaches them tricks with the football. Phillip shows the football tricks to his friends when they are outside at crèche. At bedtime Phillip’s mom tells him stories of her childhood at home and of his sisters and their grandmother. She says they will move back one day but Phillip likes Ireland best and his friends at crèche, and he wishes his sisters and grandmother were living with them too.

Mark is our final three-year-old to meet. Mark and his mam Donna have just moved homes. They are in an apartment near a big park and only one bus ride from his crèche. Mark has his own bedroom now. He used to sleep with his mam but now their apartment is bigger so he has his own bed. His favourite part of the day is bedtime stories in his mam’s bed; Mark isn’t sure if they will do that in his new bed or still his mam’s. His mam said on Sunday they will get some shelves and organise all his favourite toys and books. Uncle Eoin will come over with some of their boxes of things that have been at his uncle’s house for the past while. Mark and his mom have moved three times since he can remember. He thinks this will be the best home. They also live closer to his Granny now. Mark spends Saturdays with Granny as mam has two jobs – one during the week and one on Saturdays. Mark wishes he had more time with mam on his own but he loves being with Granny. He keeps his bike there and they go to the park where he practices going fast. Uncle Eoin says it’s nearly time to take off the stabilisers but Mark isn’t sure. Granny makes yummy dinners and they cuddle on the couch to watch their favourite shows together. She keeps a garden and Mark likes to eat the cherry tomatoes right off the plant. He likes to dig up vegetables too. Sometimes the carrots are funny-looking – all twisty, not like the ones he and mam buy in the shop. On Monday he’ll take the bus to crèche for the first time from his new house. Before, he took two buses and liked to chat with the drivers; he knew three of them. They would say ‘Good Morning Mark’ or ‘Good evening Mark – did you have a good day at creche?’ He hopes the new bus will be a double-decker so he can go up and watch out the windows and the driver will be friendly too. He wants to drive a bus or a big truck when he grows up and have his own house that is big enough for mam and Granny and him to live all together.

![]() Learning Activity 2.2

Learning Activity 2.2

Consider the three scenarios presented here. These are three children with rich lives, showing many relationships and experiences. Consider the ‘multiple identities’ of each child; consider the capacities, expressed dispositions, the experiences and culture within which they are developing their sense of self. Consider too the ‘funds of knowledge’ they have developed through these daily processes in their lives – what rich and varied knowledges do these children hold about their worlds?

Select one child from above. Create a table with four columns. Based on the scenario for the child, list out characteristics of this child under the headings set out below.

- Multiple identities – what are the various identities that this short scenario revealed for the child?

- Funds of Knowledge – what knowledges and areas of expertise are being developed due to their rich life experiences?

- Capabilities – list the various skills and strategies exemplified by the child.

- Dispositions – list out the various dispositions on display in the short scenario.

![]() Learning Activity 2.3

Learning Activity 2.3

Siolta (DES, 2010) outlines the importance of ‘empower[ing] every child and adult to develop a confident self – and group – identity’ (p. 95) and that the early years setting ‘promotes a positive understanding and regard for the identity and rights of others’ (p. 99) through the manner in which it develops all aspects of the setting. Reflecting back on the child you chose for Activity 2.2, and the table you created, develop a plan to support the development of this child’s sense of self within their early years setting, building on this child’s funds of knowledges and capabilities, and reflecting the child’s dispositions and multiple identities.

Following guidance from Siolta (DES, 2010), consider the environment, experiences and interactions within the setting in your plan. Write 150 words to outline each plan.

2.3.4 Co-construction of Knowledge and Key Stakeholders

Most Early Years settings would pride themselves on having positive relationships with families. They greet children each day and send them home again at the end of the programme, sharing brief episodes of the day’s activities, meals eaten and creative work made, with the collecting parent. Siolta (DES, 2010) promotes the idea of parents as holding ‘expert knowledge’ about their child, from their development and wellbeing, to their likes and dislikes, dispositions and interests.

How often do we, as practitioners, reflect on that expert knowledge? What processes do we have in place to facilitate meaningful interactions with parents to open up the child’s world to us? Think about the three children presented to you in the scenarios above and their complex home lives and relationships – how would we find out about their lives if not through partnership working with families?

![]() Learning Activity 2.4

Learning Activity 2.4

Look back to the plan you created to support the developing ‘self-image’ of the child you chose for the previous activities. Was there any consideration to engage with parents or other family members in developing that plan? Did they feature in any way? If not, go back to your plan and add in ways in which you feel family members could potentially be involved. If you did, go back and see how you might strengthen family involvement and proactive partnerships. Add another 100 words to the child’s plan.

Note: Standard 3: Parents and Families in Síolta (DES, 2010) could support you developing this addendum to your previous plans. Available at: http://siolta.ie/media/pdfs/siolta-manual-2017.pdf

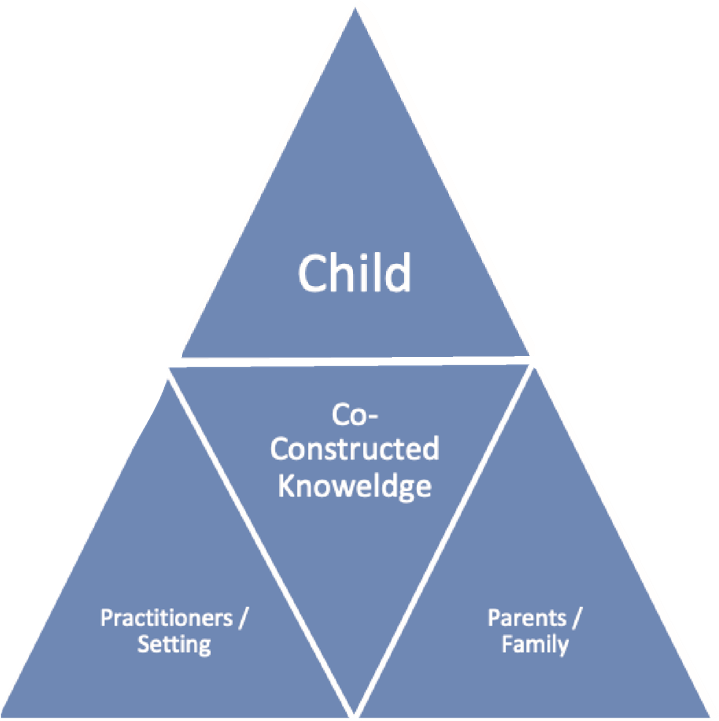

We have discussed the wide range of professional knowledges that we bring to our practice, we have acknowledged the ‘funds of knowledge’ young children develop within their many contexts and experiences, and we have noted that parents hold expert knowledge in relation to their children and have a significant role to play in extending our understanding of their child and our awareness of the richness of their lives beyond the early childhood setting. Childcare professionals, parents and the children themselves (see Figure 2.1) are the key stakeholders to be considered when we are constructing, or co-constructing, the working theories which will inform our daily curriculum plans.

Section 2.4 Siolta, Aistear, and the Image of the Child

As this unit and Unit 1 of this module have emphasised, there is a major shift underway in how we understand childhood, and in how we construct childhood, which impacts on our image of the child, and further, informs how we work with that child and their family. This new construction and understanding, this new image, has been captured and used to underpin our two national practice frameworks: Síolta (CECDE, 2006; DES, 2010) and Aistear (NCCA, 2009; 2015). Aistear clearly and repeatedly highlights that the child should be at the centre of the learning experiences that are occurring in rich early childhood settings, presenting the child as a ‘confident and competent learner’, as an active agent and as a catalyst in their own learning, in the relationships they engage in, and the interactions they drive. This notion is visually captured as well in Aistear’s thematic description of children’s learning and development.

Aistear is informed by a set of 12 principles that resonate strongly with our initial practice framework, Siolta. Aistear sees the child as unique, as a citizen in their own right, and is concerned with ensuring that equality and diversity in childhood are respected and promoted. Siolta promotes the value of early childhood as a significant and unique time. It promotes the centrality of each ‘child’s individuality, strengths, rights and needs’ (DES, 2010, p. 6) in settings, and highlights equality and diversity as core principles. Parents, relationships and the role of the adult are three of the 16 principles that underpin Siolta and equally, are grouped to form the second set of Aistear’s principles, concerned with children’s connections to others. Aistear’s third group of principles, related to children’s learning and development, cross cut throughout Siolta, and reflect the theoretical understanding of childhood as set out in Unit 1 including the theories of Vygotsky, Bronfenbrenner and Dewey (see Section 1.4).

Reflective Point 2.3

It is the premise of this module that the image that we hold of the young child will inform the manner in which we approach our practice in early childhood settings. Do we see the child as an active agent and a co-constructor of knowledge? If so, what does that mean for our daily, our weekly and annual planning? How do we understand our own role if it is not to set out the goals for the group of children, based on tried and true past plans? If we are basing our ‘plans’ or the learning experiences within our settings, on what is meaningful to each child, how do we document and exemplify the learning? What type of oversight are we working under, and how can we justify our pedagogical approach to those who require reassurance, from managers, to inspectors, to mentors?

![]() Learning Activity 2.5

Learning Activity 2.5

Access and read the following document from UNESCO: What is your image of the Child? (Author: Peter Moss)

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001871/187140e.pdf

As you read the policy brief, pay particular attention to the section that describes the early childhood educator and the shift in identity from a ‘technician’ to a ‘reflective, democratic and rich professional’. Does this description resonate with your own shifting identity? Write out 200 words of reflection on the manner in which this professional is constructed and your views in terms of your own self-identity.

Section 2.5 Co-construction within Professional Communities

Through these three years of your degree you have explored reflection on practice and used this to evidence your application of course-based knowledge to your daily work and ongoing thinking in and about Early Years settings. You have engaged with individual reflection on practice, drawing on the theories of Schon, Dewey, and Kolb, in particular. We have looked at extending our reflections through Smith’s Domains of Reflection and shifted away from structured cycles of reflection, as we looked at Moon’s method of reflective ‘unsent’ letters. (See module manuals for ECS106, ECS205 and ECS305 to review these approaches).

Building on the ideas presented through those earlier modules, through these first two units, and the ideas to follow in the next units, this module proposes that there are multiple sources of knowledge, that knowledge should be thought of in the plural (knowledges), and that these knowledges can be co-constructed with key stakeholders. These ideas are opening up our view of what knowledge is and what our role is in creating knowledge. It is ultimately freeing us up as having to be the source of all knowledge, in our work with young children and families, to the acceptance that knowledges have many forms, many origins and can be informed and shaped by context, experiences, reflection, interactions and culture, among other factors.

2.5.1 Communities of Practice

Based on the work of Lave & Wenger (1991) the concept of Communities of Practice reflects the view that professional knowledge can be created through socially situated experiences, amongst peers or colleagues. We can construct and learn new skills and knowledge through working alongside one another, engaging in professional dialogue, through work-based relationships and informed by the culture of a given setting. This activity is described by Aubrey & Riley (2016) as a ‘multifaceted’ process of learning by doing. Lave & Wenger developed their theories partly through their efforts to capture the experiences of the novice practitioner. They proposed the notion of legitimate peripheral participation for this. As the novice becomes more involved in the particular practice community, their skills and knowledge become more refined and proficient, and they develop an increasing sense of belonging and mastery. Following in the tradition of other theories on reflection in practice, legitimate peripheral participation and the Communities of Practice in which it is found, are said to be a ‘transformational process’ as members ‘learn how to fit in, how to contribute and how to change their community’ (p. 173). Wenger’s later work to further develop the Communities of Practice concept proposed the following as ‘essential characteristics’:

- Mutual engagement – as participants work and support each other

- Joint enterprise – a mediated and collective understanding of their activities

- A shared repertoire – members employ a range of related manners, tools, artefacts, ways of behaving and communicating

(Aubrey & Riley, 2016, p. 174).

The foundation of any community of practice is said to be a shared desire, by the members, to bring about change; the intention to be reflective in peer groups, to seek transformation, must be present. This is achieved through ‘regular opportunities for collaborative reflection and inquiry through dialogue’ (Wesley & Buysse, 2001, p. 118). Drawing on the work of various theorists, Wesley & Buysse (2001, p. 119) offer the following goal of a community of practice:

‘To engage in systematic collaborative discourse, reflection and inquiry, for the purpose of improving professional practice and contributing to the field at large.’

2.5.2 Learning Circles

In Year 2 of this course of study we explored the notion of Co-reflection in the module ECS201 Work Based Project, and included Learning Circles in the discussion. Circles offer a useful metaphor for collective shared learning, or knowledge coconstruction, as a circle suggests a shared space, a non-hierarchal structure, and a flow or movement of ideas and reflections, where members continue to build on earlier ideas to transform them.

Note: To refresh your thinking on this topic, you can revisit this module, and in particular, Unit 2, Section 2.5.

For those who want to explore the notion of Learning Circles in greater depth, in their own time, you can visit the following website, developed by Prof Margaret Riel, as an online forum and training space to progress the notion of learning circles. https://sites.google.com/site/onlinelearningcircles/Home/learning-circles-defined

![]() Learning Activity 2.6

Learning Activity 2.6

Dr Sheila Garrity delivered a lecture on reflection in practice at a seminar hosted by the Galway Childcare Committee in March of 2018. You can view her full lecture here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=io4zNZoB_9M

At 34:00 minutes she begins to speak about reflective communities and learning circles. For this activity, you are asked to view the video from that point to 40:00 minutes.

Garrity outlines three characteristics of learning circles; list these three points.

Think back over the past few months in your work setting. Search for times when you and colleagues engaged in practice-related dialogue. Recall these conversations as best you can, and the atmosphere around them.

Reflect on the following questions: Do you feel one or all of the three characteristics of learning circles characterised your exchange? Or were none present? Consider how those characteristics might be achieved in your work-based dialogues. Did that dialogue lead to shared knowledge creation?

Write out 200 words related to your thoughts on these questions; aim to link to each characteristic.

Section 2.6 Unit Review

This unit explores and examines our understanding of knowledge, of knowledges, the types of knowledges we hold to be valid and the source of such knowledges. The unit presents the child as a knowledge producer, derived from a sociological understanding of the child with agency. The unit outlined the concepts of funds of knowledge, multiple identities, capabilities and dispositions, particularly in relation to supporting your understanding of children’s early learning. The unit presented the concept of ‘co-constructed knowledge,’ encouraging you to consider the child, parents, others in your setting and in the community as valid contributors to a shared learning experience, within proposed learning communities or learning circles.

Section 2.7 Self-Assessment Questions

Section 2.7 Self-Assessment Questions

- Why is it important to consider the various sources and forms of knowledge or knowledges?

- Explain the concept of the child as knowledge producer.

- What does the concept of ‘co-construction of knowledge’ mean?

- How does the notion of communities of practice and learning circles relate to early years settings?

Section 2.8 Answers to Self-Assessment Questions

Section 2.8 Answers to Self-Assessment Questions

- We develop our knowledge by drawing on a range of factors – our experiences, our training, formal and informal learning, and through reflection, among other sources. Equally, young children develop their knowledge from a range of sources and experiences. If we only consider one source of knowledge, one type of knowledge, it limits the potential of our work. When we consider many sources of knowledge and many forms of knowledge, and respect the various ‘actors’ involved in our settings as knowledge holders, we expand our opportunities for meaning making, when we come to understand, support and extend children’s learning and development within our early years settings.

- Following on from the answer to Question 1, the concept of the child as knowledge producer is about respecting the varied experiences a child has had in their life, their unique home culture, the relationships therein, the ‘funds of knowledge’ that they have developed as active experiential learners. If you construct the child as a knowledge producer you are then in a position to draw on their knowledge, to expand your understanding of the child and to inform the development of the early learning curriculum in your setting. Developing your pedagogy from this perspective ensures that the curriculum is meaningful to the child, enhancing their engagement.

- Co-constructed knowledge is knowledge that is produced in collaborative, participatory and respectful processes when various stakeholders are encouraged to bring their views and perspectives to a situation in order to make meaning. In settings where children are viewed as knowledge producers, and where family members are also seen as holding unique understandings of their children, and where practitioner work to bring these varied knowledges together to understand and make sense of children’s learning moments, this is a strong example of co-constructed knowledge in action.

- According to Lave & Wenger (1991) the concept of Communities of Practice reflects the view that professional knowledge can be created through socially situated experiences, amongst peers or colleagues. We can construct and learn new skills and knowledge through working alongside one another, engaging in professional dialogue, through work-based relationships and informed by the culture of a given setting. Similar in nature, learning circles are reflective spaces in which hierarchies are pushed aside to ensure that all members feel valued and respected to share their views, knowledges and thoughts on their shared practice experiences.

Section 2.12 References

Aubrey, K. & Riley, A. (2016) Understanding and using educational theories. London: Sage.

Carr, M. (2001) Assessment in early childhood settings: Learning stories. London:

Sage. In Hayes, N. (2013) Early years practice: getting it right from the start. Dublin: Gill Macmillan.

CECDE/Centre for Early Childhood Development and Education (2006) Síolta:

National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Development and Education. Available at: http://www.siolta.ie/about.php

DCYA/Department for Children and Youth Affairs (2016) Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Charter and Guidelines for Early Childhood Education and Care. Dublin: Government Publications.

DES/Department of Education and Skills (2010) Síolta, the National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education. Dublin: Government Publications.

Garrity, S. (2018) ‘Developing early years practice through reflection’. Lecture delivered at Time & Space – Galway Childcare Committee. Institute for Life Course and Society, NUI Galway. March 24. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=io4zNZoB_9M

Hayes, N. (2013) Early years practice: getting it right from the start. Dublin: Gill Macmillan.

Hordern, J. (2016) ‘Knowledge, practice, and the shaping of early childhood professionalism’, European early childhood education research journal, 24(4), pp. 508-520.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moss, P. (2010) What is your image of the Child? Unesco Policy Brief on Early Childhood, 47, January – March. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001871/187140e.pdf

NCCA/National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (2009) Aistear: The Early Childhood Curriculum Framework. NCCA: Dublin.

NCCA/National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (2015) Aistear-Síolta Practice Guide. Available at: http://www.ncca.ie/en/Practice-Guide

Perkins, D. N., Jay, E. & Tishman, S. (1993) ‘Beyond abilities: a dispositional theory of thinking’, Merrill-Palmer quarterly, 39(1) Invitational issue: The development of rationality and critical thinking (January), pp. 1-21. In Hayes, N. (2013) Early years practice: getting it right from the start. Dublin: Gill Macmillan.

Riel, M. (2014) Online Learning Circles. Available at: https://sites.google.com/site/onlinelearningcircles/Home/learning-circles-defined

Urban, M., Robson, S. & Scacchi, V. (2017) Review of occupational role profiles in Ireland in early childhood education and care. London: University of Roehampton Early Childhood Research Centre. Available at: https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Education-Reports/Final-Review-ofOccupational-Role-Profiles-in-Early-Childhood-Education-and-Care.pdf

Wesley, P. W. & Buysse, V. (2001) ‘Communities of practice: Expanding professional roles to promote reflection and shared inquiry’, Topics in early childhood special education, 21(2), pp. 106-115.