Unit 6: Extending How We Understand and Support Children’s Early Learning

Section 6.1 Introduction

As you worked through the preceding units of this module, you were encouraged to consider a range of factors which impact on your approach to, your understanding of, support for and identification of, children’s early learning. The module began by exploring the theoretical underpinnings to the current prevailing approach to early learning, in the Irish context. You have been encouraged to develop and draw on your own deep thinking – your theorising – about what informs your own approach to early learning, and the underpinning philosophy you are developing. We say ‘developing’, because your philosophy of early education should be an ongoing process of thinking, reflecting, articulating and re-thinking.

This concluding unit of the module focuses on some underdeveloped aspects of practice that are linked to the ideas presented across the module. To that end, this unit has three main elements:

- encouraging you to consider how you could extend the curriculum to apply your emerging approach to particular topic areas and themes;

- supporting you to reflect on the learning environment and to consider this environment in its broadest sense;

- introducing you briefly to what is occurring in other contexts in regards to approaches to children’s early learning. The aim is to encourage you to consider other ways of knowing, other ways of doing, and to bring this back to critically reflect on your own approach.

Module Learning Outcomes Addressed in this Unit

- Outline the emerging Irish approach to pedagogy and curriculum development, situating this within a contemporary international context

- Apply the concept of co-constructed knowledge to recognise new ways of knowing and doing in ECEC as it concerns planning, implementing, assessing and extending the curriculum

- Assess and demonstrate how to appropriately structure the learning environment to challenge and enhance/enrich children’s thinking.

Section 6.2 Learning Outcomes

Upon successful completion of this module, and the associated activities and readings, you should be able to demonstrate the ability to:

- Explain how to link children’s working theories to literacy and STEM concepts in real terms: Scenarios Mark, Philip and Sarah.

- Analyse the role of digital technology in offering new ways/opportunities to observe and document children’s interests and play

- Identify areas where you could benefit from further professional development, for example in the use of digital technologies to support pedagogy, and in developing your subject-knowledge expertise in early mathematical concepts & language, and creative teaching methodologies

- Demonstrate the ‘teacher-led’ element of an emergent inquiry-based pedagogy, extending children’s interests to support learning in particular curricular areas

- Discuss how various elements of children’s learning environments afford different opportunities for children’s learning experiences

- Identify similarities and differences between Aistear, the Irish early learning framework, and approaches to early learning as developed in other international contexts

- Contextualise the concepts of other ways of knowing, other ways of doing, and your understanding of multiple knowledges and practices within early years approaches

Section 6.3 Extending the Curriculum

In this section, you will explore how you might work with your knowledge of a child’s dispositions and capabilities, funds of knowledge and multiple identities (see Unit 2) to create learning opportunities that build on their emerging interests. To illustrate this approach, we will re-visit our three young friends from Unit 2, Phillip, Sarah and Mark. We will use their personal stories and what we have learned about them, as the basis of our planning.

6.3.1 Engaging with Early Mathematical Concepts

Reflect back to Unit 2, Section 2.3.3 when we met Mark. In units 3, 4 and 5, Mark’s interest and lived experiences resulted in a group research project that unfolded over time. This was facilitated by the process of multiple listening and collaborative inquiry.

The practitioners decided to set time aside to interpret and reflect on the research project and to discuss the connections the children and Mark were making as they mapped out the routes and the important landmarks they saw on their way to crèche each morning. An important aspect of this discussion was the opportunities for the children to link their everyday encounters, observations and questions to key mathematical concepts.

The practitioners revisited their pedagogy for learning, with the important aim of supporting children’s learning dispositions and capacities to actively explore and to be curious and persevere. This discussion focused the practitioners to become more intentional in their teaching practices, and to consider their subject knowledge and pedagogical knowledge of mathematical learning in the early years. The practitioners agreed that it was their role to scaffold the children’s learning by sustaining the children’s motivation and providing resources to support mathematical thinking (French, 2013). They reflected on their teaching methodologies, which included modelling using mathematical language, open-ended questions and planning learning opportunities for trial-and-error and exploration in a meaningful context. Mathematical concepts such as sequencing, classifying, comparing, shape, sorting, locating, measuring, grouping, awareness of time and counting were identified, all of which were relatable to the mapping activity.

The practitioners also devised a list of mathematical language that could be intentionally used for pre-planned activities, and for the moments of spontaneous learning. As the children mapped out and described their journeys, their conversations about the environment encouraged the use of positional language such as: in front of, behind, on and under.

Learning Activity 6.1

Reflect on the daily routines and transitions in your setting. Think about how these routines can be used to support and extend the children’s mathematical thinking and learning. Consider the important mathematical concepts such as one-to-one correspondence, conservation, number sequencing, time, and using mathematical language in a meaningful context. One-to-one correspondence is the ability to match an object to the corresponding number and recognise that numbers are symbols to represent a quantity. It is very common for children to learn to count without understanding the concept of one-to-one correspondence. To help you with this activity, copy and paste the following link.

Early Childhood Literacy and Numeracy by Marilyn Fleer and Bridie Raban: https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2015/ed13-0077_ec_literacy_and_numeracy_building_good_practice_resources_booklet_acc.pdf

Reflective Point 6.1

Early math is not about the rote learning of discrete facts like how much 5 + 7 equals. Rather, it’s about children actively making sense of the world around them. Unlike worksheets with one correct answer, open-ended, playful exploration encourages children to be divergent thinkers and solve problems in real situations (McLennan, 2014).

6.3.2 Introducing STEM Subjects in the Early Childhood Setting

Reflect back to Unit 2, Section 2.3.3 when we met Philip. The practitioners recognise that Philip brings with him multiple identities and funds of knowledge. Philip’s religious and cultural background is integral to his sense of self, and so is his love for football. The practitioners are passionate about designing a curriculum that applies the funds of knowledge approach, where they connect the curriculum with the home and community.

The practitioners had noticed that in recent weeks, Philip and his friend Sophie had started collecting football cards. In their conversations together, Philip and Sophie discussed their favourite teams. At circle time, the practitioner asked Philip and Sophie to talk about their favourite football team. Philip had drawn a picture of himself wearing a favourite football jersey. The practitioner asked Philip and Sophie if they would like to have their own football team with their own football jersey. Philip and Sophie were excited about this prospect. This initiated a STEM-themed activity that led to Philip and Sophie and all the children designing football jerseys.

First the children conducted research online, looking at various teams, what their jerseys looked like, the colours, emblems or logos. Philip found a team based in the city his sisters lived in, which was very exciting for everyone involved.

Next, a software programme was used and the children were able to type their names, and numbers, select colours and create graphic images for their t-shirts. They were able to print off these images and display them around the room. Using a borrowed vinyl cutter and heat press, the children produced their own unique football jersey. The children were delighted with how professional their jerseys looked. They decided to put on an exhibit of their designs, and invite their families and friends to attend. They created booklets with all the images of the designed jerseys included.

This project allowed the children to see the many uses of technology. Up until now, the children had used the computer to research their questions and ideas. However, in this project the children were able to combine technology and real materials to help them visualise and engineer a concept, and bring it to the next stage of construction and completion.

Reflective Point 6.2

According to Roberts (2016), considering STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) in the early years context refers to the interconnection of at least two curricular areas. The following presentations demonstrate how our understanding of how children learn has evolved, with the child seen at the centre of the active learning experience. An informed, reflective practitioner will use their expertise to create connections across many of the curricular areas, and plan a curriculum that facilitates children to think in a more connected and holistic way.

- Look at the following presentation: Roberts, P. (2016) STEM in early childhood: how to keep it simple and fun. Early Childhood Australia National Conference. Available at: http://www.ecaconference.com.au/wpcontent/uploads/2016/11/Roberts_P_STEM.pdf

- In your own words, choose the key points that resonate with you as both a learner and an Early Years Practitioner.

- To find out more about early STEM for the under 3’s, review the following document: Joslin, L. & Boyd, S.(n.d.) Infant and toddler STEM: science, technology, engineering and mathematics Powerpoint presentation. Childcare quality and early learning: Center for Research and Professional Development University of Washington. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/cqel/PDFs/Presentations/Infant%20&%20Toddler%20STEM%20NW%20Institute%202014%20Powerpoint.pdf

Learning Activity 6.2

Reflecting on Philip’s story, consider and demonstrate how you as the practitioner would document what Philip learned in this project, and how this learning would be shared between the home and the setting.

6.3.3 Supporting Children’s Emerging Language and Literacy

Reflect back to Unit 2, Section 2.3.3 when we met Sarah. The key person in the setting has observed how Sarah often takes on a nurturing role with her peers and takes on roles of responsibility with ease. At a reflective meeting, Sarah’s key person highlights all of her strengths but also identifies the need for Sarah to focus on herself and for her to see her capacities and knowledge represented in a meaningful way. The key person is also aware that Sarah’s dad returns home one weekend a month, and this is a very special time for Sarah. When her dad goes back to work, Sarah is very able to move on with daily life. However, she stays closes to her key person and will use her favourite story as a way to have one-to-one time with her key person.

Sarah enjoys free writing and mark making, and it was from this observation that the idea of Sarah’s diary was born. The diary became a very important part of Sarah’s routine: she would sit with her key person and together they would write her stories. Some of the stories included facts about the farm, and what happens in the hospital where her mother works, as well as Sarah’s free drawings. This diary was also shared between the home and setting, and Sarah’s dad would write about their weekends together. Sarah enjoyed reading these stories with her key person.

The diary was beautifully decorated by Sarah, and she took pride in seeing her name written down as the author and illustrator of her own book. It was interesting to see Sarah read from memory as she shared her stories with her friends. This gave Sarah’s key person the idea to record Sarah telling her story using digital technology. This provided a new medium for Sarah to see her stories represented.

French (2013) cites Sylva et al. (2004) stating that it is what parents, carers and educators do with children (reading with children, talking to them, sharing stories), which makes the difference to children’s literacy learning outcomes.

Learning Activity 6.3

Copy and paste the following links to read more about Early Literacy development in the early years setting.

• Early literacy and numeracy matters by Geraldine French: https://arrow.dit.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1065&context=aaschsslarts

• Mark Making Matters, Young children making meaning in all areas of learning and development: Department of children, schools and families. Available at: https://www.foundationyears.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2011/10/mark_marking_matters.pdf

Reflective Point 6.3

According to Purpura & Napoli (2015) the critical connection between early literacy and early numeracy occurs between language and print knowledge, and informal numeracy (what is learned in everyday situations) and numeral knowledge.

Learning Activity 6.4

Refer back to Unit 4, Section 4.3, related to the Early Years Education

Focused Inspections. In particular refer to the inspection tool, the Quality Framework, Area 2 – Quality Processes that Support Children’s Learning and Development. Beginning on page 19 of the Quality Framework document, Area 2 is set out in a table format, with eight relevant Outcomes and a subset of Signposts for Practice.

Access the Framework document here: https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Inspection-Reports-Publications/Evaluation-Reports-Guidelines/guide-to-early-yearseducation-inspections.pdf

Consider the processes you engaged with, as you planned for Philip, Sarah and Mark’s learning experiences, above. Read through the Signposts listed under these eight Outcomes. Tick off those that underpinned your thinking. Highlight those that you did not consider.

These are areas that potentially need further attention and support in your ongoing professional development.

Learning Activity 6.5

Create a professional development strategy, to address the issues emerging out of L.A. 6.5 Your strategy may consider small steps such as posting the Signpost list in your work area, or bringing the list to team meetings for discussion and support. Note some plans for yourself, up to 200 words.

Section 6.4 Reflecting on the Resources and the Learning Environment in its Broadest Sense

Schematic play is when children repeatedly practise different ideas or concepts (Brodie, 2016). Emma, aged 2, has been repeatedly exploring rotation. This interest of hers is particularly evident in the outdoor environment, where practitioners have observed Emma’s deep involvement and thinking when playing with the water wheel, and when she is spinning around or twisting, and wrapping the hand ribbons around the tree branches.

This observation stimulated a conversation between the practitioners about the affordances of the outdoor environment and indoor environment, and how they support or inhibit the children’s schematic learning. Their reflections encouraged the practitioners to look at how the indoor and outdoor learning environment was structured to support children’s emotional wellbeing, decision-making and schematic thinking, and the availability of open-ended materials (also called loose parts) for children of all ages.

Learning Activity 6.6

To read more about how to create enabling environments for infants and toddlers, copy and paste the following links:

- Using open-ended materials: http://www.aistearsiolta.ie/en/CreatingAnd-Using-The-Learning-Environment/Resources-for-Sharing/Openended-materials.pdf

- My Space: Creating enabling environments for young children. Oxford: Oxfordshire County Council. This document is related to the Early Years Foundation Stage for Ofsted-registered settings.

https://www2.oxfordshire.gov.uk/cms/sites/default/files/folders/documents/childreneducationandfamilies/informationforchildcareproviders/Toolkit/My_Space_Creating_enabling_environments_for_young_children.pdf - Government of Saskatchewan. Early Learning and Child Care Branch Ministry of Education (2010) Play and exploration for infants and toddlers. Available at: http://publications.gov.sk.ca/documents/11/82949-Final%20Infant%20Toddler%20Companion%20Booklet.pdf

For more information about resources, access the folder titled Enabling Environments available on Blackboard under the section Learning Materials.

Reflective Point 6.4

Consider what materials could be added to the outdoor and indoor learning environment to support Emma’s rotation schema.

6.4.1 Documenting Children’s Learning Experiences in the Digital Age

Young children today are growing up in a new cultural context in which the emergence of the digital age (beginning with the invention of the transistor) has created new opportunities for play. They are considered ‘digital natives’, as their world has always contained and been influenced by digital technologies.

The term ‘natives’ signals a comfort with technology older people don’t always have. A significant problem is how parents and practitioners conceptualise the use of technology in the early years, and how they view, understand and value the idea of ‘digital play’.

Edwards (2016) discusses the concept of ‘converged play’ as a new form of play. He proposes the notion of web-mapping as a means of understanding and combining digital and traditional play materials in creative, fluid and flexible ways. Just as in the processes involved in pedagogical documentation, ‘web-mapping’ is a tool for assessing children’s learning and interrogating the implications of digital play for early years practice and provision. In a research study conducted by Edwards (2016, p.524) ‘web-mapping was also seen as a useful tool for understanding and focusing on the children’s home interests rather than relying only on the interests teachers might observe in the classroom’.

Reflective Point 6.5

Building on Edwards’ (2016) research, consider how digital tools can be used to bridge two of the key ‘micro-systems’ in a young child’s life – the home and the early years setting. Think about how technology provides evidence of children’s ‘raw materials’ that accompany them between settings. Look back at Section 5.5, on the hidden curriculum. How might digital technologies support young children to share their contextual knowledge and meaningful experiences with you, their peers, and their families?

Learning Activity 6.7

Download the following article and refer to the five main influences of webmapping on pages 524 – 527. Reflecting on your own practice, would some of these influences enhance your own engagement with an emergent curriculum, possibly address ‘gaps’ in your own practice? Select one ‘influence’ and write out 200 words on your perceived ‘gap’ outlining how this new perspective might enhance your practice.

- Edwards, S. (2016) ‘New concepts of play and the problem of technology, digital media and popular-culture integration with play-based learning in early childhood education’, Technology, pedagogy and education. Available at: https://www-tandfonline-com.libgate.library.nuigalway.ie/doi/pdf/10.1080/1475939X.2015.1108929?needAccess=true

6.4.2 The Emotional Environment

We often think of the physical environment when planning our early years curriculum. We consider the space, in and out of doors, the equipment and furnishings, the layout and even the routine in terms of how we organise the environment. This section briefly considers the ‘emotional environment’, or the atmosphere that we create, within our settings, and its impact on the child who attends. Hayes & Kernan (2008) promote the concept of a ‘nurturing pedagogy’ which foregrounds the relational element of practice in early childhood contexts. While the term ‘care’ features within a widely-accepted title for our sector – early childhood education and care – a focus on the educational elements of early years practice has sought to elevate and professionalise the sector. This has resulted in the care element often being sidelined (Hayes, 2008).

In an attempt to reclaim the ‘care’ element of our work, Hayes (2007, in Hayes & Filipovic, 2018) suggests the alignment of care with the concept of nurture; to consider how we nurture children’s development, nurture relationships with families, nurture a welcoming and inclusive environment within our settings. This creates a more dynamic and thoughtful understanding of our work with young children and families, though still within the caring realm.

Hayes & Filipovic (2018) further relate a notion of nurturing pedagogy to the proximal processes within the bioecological model (see Unit 1, Section 1.4.2) of human development. Discussing proximal processes, and referencing Bronfenbrenner & Morris (2006) Hayes & Filipovic suggest these ‘form the basis of day-to-day experiences and can facilitate the development of positive, generative dispositions of curiosity, persistence, responsiveness and engaged activity while inhibiting the more disruptive dispositions of impulsiveness, explosiveness, distractibility or apathy, inattentiveness, unresponsiveness and feelings of insecurity’ (2018, p. 222).

Building on these ideas, we are encouraged then to consider the atmosphere that we create within our settings, how we nurture relationships, as a means of supporting children’s early learning capacities and dispositions, as well as a means to nurturing their wellbeing and identity.

Section 6.5 Approaches to Children’s Early Learning in Other Contexts

Early units in this module encouraged you to consider other ways of knowing and other ways of doing, to be reflective, open-minded and thoughtful in your approach to your practice in early childhood settings. This module has focused on the emerging inquiry-based approach to early childhood education that is promoted in Irish policy and practice frameworks. In this section, you will look briefly at practices in other contexts. You are encouraged to reflect on how these practices could inspire your own approach.

Reflective Point 6.6

Recall in the Year 2 module, Implementing the Early Learning Curriculum, you were introduced to the Reggio Emilia approach. Recall this was described as an approach to early learning, rather than a ‘curriculum model’; that it was grounded in a particular community and culture. The Reggio approach has a unique history that led to this particular approach to ECE, as it developed in response to the context in which it was based. While you may find ideas, theories and practices that resonate with you within this approach, you are encouraged to reflect on whether these elements ‘fit’ with the context you work in, for the children in your setting, and with the families you collaborate with. If you feel certain aspects do resonate, you were encouraged to adapt them so that they resonate with the work that you do in your own unique context.

Please keep this advice in mind as you consider the following approaches.

6.5.1 Te Whariki

Just as Ireland has Aistear as our early childhood curriculum framework, Te Whariki – Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa – is the early childhood framework in place in New Zealand (Ministry of Education, 1996). Developed in 1996, it was designed to support children’s early learning in ECEC settings and to ‘take account of and promote the particular cultural influences that arise through cultural diversity and biculturalism’ (Soler & Miller, 2003, p.60) unique to the New Zealand context. Through the development of the early learning framework, creators sought to promote bi-culturalism and diversity in the community. They took on board progressive contemporary approaches to early learning, including socio-cultural theories and sociological perspectives of children and childhood.

It is no surprise then that Te Whariki presents the following vision for children within their early childhood curriculum framework:

‘Competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society’ (Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 5).

Reflective Point 6.7

In what ways does this vision reflect similar ideas promoted in Aistear?

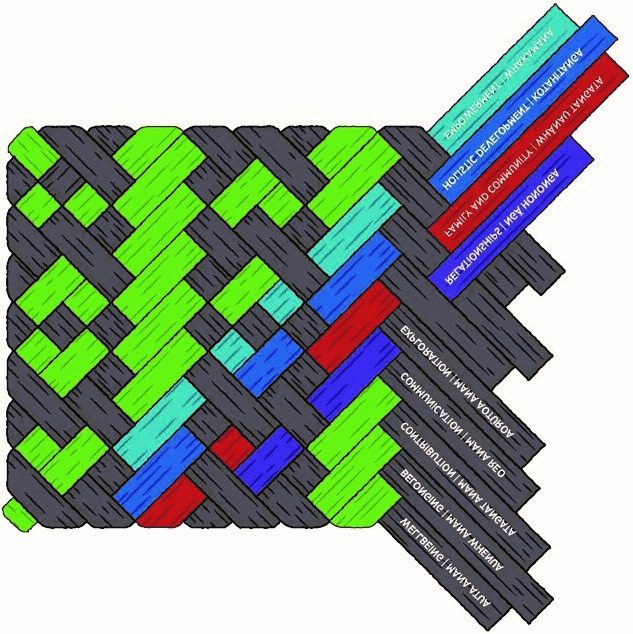

The term ‘Te Whariki’ holds many meanings within Maori tradition. It is used as a metaphor for the coming together of cultures, traditions and values with contemporary ideas and knowledges concerning early learning and childhood. Whariki refers to the traditional woven mat ‘on which everyone can stand’ (Soler & Miller, 2003, p. 62). Te Whariki refers to the practice of mat weaving. The mat represents the weaving of traditional understandings and values with contemporary knowledge. It also represents the weaving of various cultures and peoples within the diverse communities in New Zealand, to offer practical and metaphorical support.

(From Ministry for Education, 2017)

‘The kōwhiti whakapae whāriki depicted below symbolises the start of a journey that will take the traveller beyond the horizon. The dark grey represents Te Kore and te pō, the realm of potential and the start of enlightenment. The green represents new life and growth. The purple, red, blue and teal have many differing cultural connotations and are used here to highlight the importance of the principles as the foundations of the curriculum’ (p. 11). (See Figure 6.1).

The image above illustrates the weaving together of the principles and strands of the curriculum framework, including the goals, learning outcomes and pathways to school. The framework is strongly focused on the following throughout the ECEC setting, including the local community in which a setting is based:

- supporting educational transitions

- creating inclusive environments where barriers to participation are removed

- recognising and valuing respectful, responsive and reciprocal relationships

Children’s identities are privileged through the framework, and in practice. The home languages and cultures of children attending settings are valued. The curriculum approach recognises children in New Zealand are often exposed to and are therefore learning through more than one language. Some 200 languages are used in the region, including New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL). Children are seen as multilingual and multi-literate (Ministry of Education, 2017). Settings are encouraged to promote the use of NZSL, as it is an official language of the country, and to provide opportunities for all young children to learn the language.

While Te Whariki is an overarching curriculum framework, and early childhood settings are expected to engage with the framework, it was designed to be adaptable and flexible for use in unique contexts and communities. In particular, the unique identity, language, and culture of each child should be linked to learning experiences, to reflect local values and experiences, what is ‘known’ and therefore what is meaningful to children, in their own contexts.

Reflective Point 6.8

According to Soler & Miller (2003) ‘Te Wha¨riki views the curriculum as a complex and rich experiential process arising out of the child’s interactions with the physical and social environment’ (p. 63). Refer back to Units 1 and 2 of this module. What theories, and which theorists who discuss early learning are captured in this statement?

Learning Activity 6.8

You can access the revised Te Whariki Early Childhood framework here: https://education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Early-Childhood/ELS-TeWhariki-Early-Childhood-Curriculum-ENG-Web.pdf

Similar to the Aistear Síolta Practice Guide, Te Whariki online offers resources to support engagement with Te Whariki in practice. It can be accessed here: https://tewhariki.tki.org.nz/

With Aistear in mind, scroll through both these sites, and look for areas of divergence and areas of convergence between the Irish and the New Zealand early childhood frameworks. What stands out to you as surprising, inspiring or challenging?

What valuable learning is there in Te Whariki that might be useful in the Irish context? What adaptations might be needed to make this meaningful to Irish children?

Write 250 words to capture your thoughts.

6.5.2 Indigenous Learning Frameworks in the Canadian Context

The New Zealand approach to early learning resulted in a single all-embrasive framework that reflected the ‘bi-cultural’ traditions of the nation. It was set within a diverse and multicultural context. In Canada, however, a distinct Indigenous Early Learning and Childcare Framework was developed through extensive collaboration with indigenous peoples. Its aim was to reflect the ‘unique cultures, aspirations and needs of the First Nation, Inuit and Métis children across Canada’ (Government of Canada, 2018, n.p.).

A set of nine principles underpins this overarching framework. The framework includes respect for indigenous knowledges, languages and cultures. It recognises the right of determination of these three distinct peoples. It takes a child- and familycentred approach. It also includes familiar principles, such as quality in service provision, inclusion, access, flexibility and adaptability, transparency and accountability. Finally, the Canadian framework promotes respect, collaboration and partnerships. This national framework includes three Distinction-based Frameworks. These reflect the three indigenous groupings in Canada – First Nation, Inuit and Métis peoples, with their unique cultures, knowledges and languages.

The frameworks recognise that ‘Children hold a sacred place in the cultures of indigenous peoples’ (Government of Canada, 2018, n.p.). The aim is to support the long-term development of children, nestled within their communities and cultures. Working closely with families, elders and others in the communities, the frameworks also aim to address long- term disadvantage, social exclusion, and cultural disruption for many extended members of the communities. It is a sensitive approach which recognises the systemic structures, powers and policy regimes that have contributed to historic disenfranchisement of the indigenous peoples.

The Framework references the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, held by the Canadian Government from 1991 to 1996, as well as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Royal Commission recommended that ‘all Aboriginal children, regardless of status or location, have access to dynamic, culture-based early childhood education’. The UN Declaration highlights ‘the right of indigenous families and communities to retain shared responsibility for the upbringing, training, education and well-being of their children, consistent with the rights of the child’.

6.5.3 Indigenous Knowledges

Ball (2012) highlights the various knowledges children are exposed to within indigenous communities that support their development as individuals. Their individual identity develops within this rich community. These children are holders of their unique heritage, customs and cultures. These include:

Communal Knowledge: Passed on to children through their involvement with, observation of and participation in their local cultural practices, including languages, values, traditions and daily activities.

Ancient and Modern Traditional Knowledges: Referring to Emery (2000, in Ball, 2012) there is a distinction between ancient traditional knowledges, that have been passed down through generations, and contemporary cultural knowledge, developed through the adaption of traditions to presentday circumstances and contexts. These new ‘knowledges’ reflect the dynamic cultures that are alive today, rather than simply being considered a hold-over from the past. These newer knowledges will also be passed down, and in time come to represent traditional knowledges.

Development of Identity: A child’s individual identity formation is grounded in their understanding of their group identity. Through daily practices and activities, children develop a sense of who they are, their role and place, their relationships with others, and their own capacities and strengths. This sense of self is linked to their present-day family members, but also to their heritage and ancestors.

Heritage Language Acquisition: Language acquisition within indigenous communities ideally develops experientially, through engagement with daily life. Individual dialects reflect each people’s unique heritage, experiences, traditions and cultures. There is a strong spiritual dimension to language acquisition. It is based on the belief that the Creator provided them with their unique language. Its use supports a deeper individual connection to the Creator.

Literacy of the Land: Building on the heritage language acquisition, there is recognition of the deep connection of their languages to the land, to wildlife,

to natural plant life and the use of these in daily life. Children learn not only to appreciate and value their land, but to respect and protect the land as their birthright.

Nurturing the Child’s Spirit: According to Ball (2012, p. 289) many parents feel it is important to support children to develop a ‘sense of one’s own spirit and one’s relationship with one’s ancestors and with the benevolent Creator’. It is believed that a child who has a strong sense of their spiritual identity will be better prepared to overcome adversity in life.

The Right Time: Traditional child-rearing practices within indigenous communities allow for children to develop at their own pace. The children are supported through their daily activities, with increasing challenges and responsibilities offered when the time is right for each child. Ball (2012, p289) talks about how children become ‘attuned’ to the various temporal elements in their world. They are encouraged to notice the changing seasons, ‘life cycles of plants and the migratory patterns of animals, fish and birds. They participate in cultural events with this temporal element to their own development and learning is easily aligned to their wider culture and context.

(Adapted from Ball, 2012)

This discussion of the increasing awareness of traditional knowledges, particularly as this relates to work within early learning contexts, brings this module full circle. Look back to the earlier opening units. Recall the discussion in Unit 1 of how the discourses concerning ‘childhood’ as a cultural subgroup in society informs how we think about children. This impacts on how we work in early learning settings. In Unit 2, Urban highlighted the need for us to think about various knowledges, as opposed to one agreed knowledge. We need to consider various practices and values in early years work, to truly develop inclusive, respectful approaches to practice.

Ball (2012, p. 286) refers to the ‘culturally dissonant learning environments’ that young indigenous children can be exposed to in early learning settings. This happens if the setting contradicts, devalues or is ignorant of the cultural and traditional experiences children have had in their homes and local communities. This occurs when particular skills and knowledges are privileged over others. Urban (2019) criticises the lack of appreciation for cultural difference in the OECD International Learning and Child Well-Being Study (OECD, 2016). Urban (2019) refers to ‘diverse and culturally embedded local practices of education’ which tend to be devalued in such studies. Often, such practices are not even considered in national or even international assessments of children’s learning achievements.

Urban (2019) is concerned with the increasingly globalised reach of ‘homogenising’ curriculum and assessment regimes. These promote western or minority world values at the expense of locally-developed knowledges, practices and values. In these ‘neocolonial’ practices ‘physical colonialization has been replaced by political, economic and cultural dominance’ (p. 11). This approach threatens to erase the types of locallydeveloped knowledges that have been highlighted through this section of this final unit.

Learning Activity 6.9

Review the suggested ‘indigenous knowledges’ outlined above, as adapted from Ball (2012). Think about the children you work with now or have in the past, both children from minority cultures and those from the majority culture. Try to recall any unique knowledge, customs, or practices that you learned about, perhaps from the family of this child, or from the child, that you were unaware of previously. How might these elements of the child’s identity be supported in your early years setting? What ways could you explore these areas with the child and their peers? Set out your thoughts on this topic in 250 words.

Section 6.6 Unit Review

This last unit the module Understanding Children’s Early Learning focused on three main areas.

- First, the unit outlined how practitioners might extend their support of children’s learning experiences. You were encouraged to engage with particular curriculum areas, such as STEM, language and literacy development, and foundational mathematical concepts.

- Next, the unit looked at areas of the environment, and linkages between these that may be otherwise under-considered. This included the indoor/outdoor areas, the home/setting link and the emotional environment in our settings.

- Finally, the unit included examples of approaches to practice in other contexts: Te Whariki, and the Canadian ‘multiple framework’ approach.

These examples from other countries contextualise the concepts of other ways of knowing and other ways of doing. They encourage a broader understanding of multiple knowledges and practices within early years settings.

The unit ended with Urban’s (2019) criticism of the global imposition of western early learning models, and the approaches and assessments based on them. These global approaches prioritise western contexts, at the expense of locally-developed approaches and the privileging of local knowledges, practices and values. The examples from New Zealand and Canada, as well as the stories of Philip, Sarah and Mark, reveal the richness of children’s lives, backgrounds, families and communities. It is the important role of early years practitioners to seek out and appreciate children’s unique identities. Practitioners can build on these and celebrate them in their early learning settings. It is important to recognise and respect the deep, rich learning that occurs in all the contexts a child inhabits: home, community, and early years setting.

Section 6.7 Self-Assessment Questions

- In developing an intentional approach to supporting children’s engagement with mathematical concepts, what teaching methodologies did the practitioners make use of, in Section 6.3.1?

- Based on the example in Section 6.3.3, involving Sarah and her emergent language and literacy, outline how the guidance set out through this section promotes the development of an emergent inquiry-based curriculum, and illustrates the concept of ‘co-construction of knowledge’.

- Section 6.4 explored the environment of early learning, and considered three areas practitioners should be aware of as they seek to understand and support children’s early learning. What were the areas outlined, and why are these important?

- What are some of the differences and similarities between Te Whariki and Aistear?

- What are the indigenous knowledges, as highlighted by Ball (2012). How might these inform practice in early years settings that are attended by children in these contexts? What do they reveal about how childhood is ‘constructed’ within indigenous cultures in Canada?

Section 6.8 Answers to Self-Assessment Questions

- Initially, the practitioners set time aside to interpret and reflect on the ongoing research project and to discuss the connections the children were making. From this point, the teaching methodologies they adopted included modelling using mathematical language, open-ended questions and planning learning opportunities for trial-and-error and exploration in a meaningful context. They identified mathematical concepts and mathematical language that could be intentionally used across the daily curriculum, in support of children’s engagement with mathematical concepts and the expansion of their mathematical knowledge.

- An emergent and inquiry-based curriculum develops from the close observation and awareness of children’s interest by practitioners, potentially in partnership with parents and through conversations with the children. Identified areas of interests can become the ‘vehicle’ by which children’s knowledges, concepts, vocabulary and skills can be extended. This may be achieved through careful documenting, reflection and effective planning by responsive practitioners. Engaging with a range of stakeholders, including parents and children, offers multiple perspectives of the emerging interest areas. The different stakeholders provide varying meanings. These clarify and expand how the situation is interpreted or ‘constructed’ by each stakeholder. They offer different insights about what interests the child, and how this area is meaningful for her/him.

Section 6.4 encouraged practitioners to consider both the outdoors and indoors environments when planning for, supporting and extending children’s emerging interests, as each context affords different, yet valuable, learning opportunities. Next, the section highlighted the links between the home learning environment and the early years setting. It introduced Edwards’ (2016) web-mapping as a tool to enhance partnerships between these key micro-systems. Finally, the section briefly touched on the emotional environment, highlighting the importance of care, re-constructed as nurture. This supports proximal processes and the development of positive generative dispositions in young children. In other words, children’s emotional security provides a secure base on which to develop relationships and interactions with others in their microsystems, be that adults or peers. Further, such a context facilitates exploration, trial-and-error, and inquirybased learning, as the children feel a sense of trust in those around them.- Te Whariki is uniquely situated in the New Zealand context, embracing the diversity of the country, in particular the bi-cultural traditions. The approach is strongly situated in local communities and promotes learning through multi-lingual opportunities, supporting children’s potential multi-literacy. This includes encouragement to learn one of the national languages: New Zealand Sign Language. Both Aistear and Te Whariki were developed from a sociological perspective of early childhood, underpinned by socio-cultural theories. This approach recognises children as being competent and confident, with effective learning experiences being both contextual and relational. That is, learning occurring through social interactions, in relationships with others, situated in rich learning environments.

- Ball (2012) suggests the following as examples of indigenous knowledges: communal knowledge; ancient and modern traditional knowledges; development of identity; heritage language acquisition; literacy of the land; nurturing the child’s spirit; acknowledging the right time for each child to have a particular learning experience. Within the First Nations, Métis and Inuit culture, childhood appears to be constructed as deeply enmeshed with the culture, heritage and traditions of the child’s community. Children are seen as guardians of their culture and land as both a right and a responsibility. Equally, they are seen as capable individuals with the potential to develop skills and knowledges through contextual and experiential learning opportunities. This construction includes respect for each child’s individual journey, and an awareness that the time needed for that journey will be different for each child.

Section 6.9 Reference List

Ball, J. (2012) ‘Identity and knowledge in indigenous young children’s experiences in Canada’, Childhood education, 88(5), pp. 286-291.

Emery, A. (2000) Integrating indigenous knowledge in project planning and implementation. Washington, DC: CIDA, ILO,KIVU Nature, & World Bank. Retrieved 26 July 2012, from http://www.worldbank.org/afr/ik/guidelines/index.htm

Brodie, K. (2016) ‘Schematic play in early years, and what it can reveal about deep-level learning’. Available at: https://www.teachwire.net/news/schematic-playin-early-years-and-what-it-can-reveal-about-deep-level-learn

Bronfenbrenner, U. & Morris, P.A. (2006) ‘The bioecological model of human development’, in Lerner, R.M. & Damon, W. (eds.) Handbook of child psychology: theoretical models of human development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, pp. 793828.

Department for Children, Schools and Families (UK) (2008) The National Strategies Early Years: Mark Making Matters, Young children making meaning in all areas of learning and development. DCSF. Available at:

https://www.foundationyears.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ mark_marking_matters.pdf

Department of Education and Skills (DES) (2018) A Guide to Early Years Education Inspection. Dublin: DES. Available at:

https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Inspection-Reports-Publications/ Evaluation-Reports-Guidelines/guide-to-early-years-education-inspections.pdf

Edwards, S. (2016) ‘New concepts of play and the problem of technology, digital media and popular-culture integration with play-based learning in early childhood education’, Technology, pedagogy and education, 25(4), pp.513-532.

Fleer, M. & Raban, B. (2007) Early childhood literacy and numeracy: building good practice. Australian Government. Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

Fleet, A., Patterson, C. & Robertson, J. (2017) Pedagogical documentation in early years practice: seeing through multiple perspectives. London: Sage.

French, G. (2013) ‘Early literacy and numeracy matters’, Journal of early childhood studies, OMEP, Vol. 7, pp. 1- 20.

Government of Canada (2018) Indigenous Early Learning and Childcare Framework, Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-socialdevelopment/programs/indigenous-early-learning/2018-framework.html#h2.0

Government of Saskatchewan (2010) Play and Exploration for Infants and Toddlers, A companion booklet to Play and Exploration: Early Learning Program Guide. Saskatchewan Ministry of Education.

Hayes, N. (2008) ‘Teaching matters in early educational practice: the case for a nurturing pedagogy’, Early education and development, 19(3), pp., 430-440.

Hayes, N. & Kernan, M. (2008) Engaging young children: a nurturing pedagogy. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

Hayes, N. & Filipović, K. (2018) ‘Nurturing “buds of development”: from outcomes to opportunities in early childhood practice’, International journal of early years education, 26(3), pp. 220-232.

Joslin, L. & Boyd, S.(n.d.) Infant and toddler STEM: science, technology, engineering and mathematics Powerpoint presentation. Childcare quality and early learning: Center for Research and Professional Development University of Washington. Available at:

https://depts.washington.edu/cqel/PDFs/Presentations/Infant%20&%20Toddler% 20STEM%20NW%20Institute%202014%20Powerpoint.pdf

McLennan, D. P. (2014) ‘Making math meaningful for young children’, Teaching young children, 8(1), pp. 20-22. Available at: http://www.naeyc.org/tyc/article/making-math-meaningful

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) (n.d.) Aistear/Siolta practice guide: Using open-ended materials Available at: http://www.aistearsiolta.ie/en/Creating-And-Using-The-LearningEnvironment/Resources-for-Sharing/Open-ended-materials.pdf

New Zealand Ministry of Education (1996) Te Wha¨riki. He Wha¨riki Ma¨tauranga mo¨ nga¨ Mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early Childhood Curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

New Zealand Ministry of Education (2017) āTe Whāriki He whāriki mātauranga mō ngmokopuna o Aotearoa. Early Childhood Curriculum (Revised/Updated). Available at: https://education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Early-Childhood/ELS-Te-Whariki-Early-Childhood-Curriculum-ENG-Web.pdf

New Zealand Ministry of Education. Te Whariki Online. Available at: https://tewhariki.tki.org.nz/

Oxfordshire County Council (2008) My Space: Creating enabling environments for young children. Oxford: Oxfordshire County Council, pp.1-36.

OECD (2016) The International Early Learning and Child Well-Being Study, Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/education/school/the-international-early-learning-and-childwell-being-study-the-study.htm

Purpura, D.J. & Napoli, A.R. (2015) ‘Early numeracy and literacy: untangling the relation between specific components’, Mathematical thinking and learning, 17(23), pp.197-218 .

Roberts, P. (2016) STEM in early childhood: how to keep it simple and fun. Early Childhood Australia National Conference. Available at: http://www.ecaconference.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Roberts_P_STEM.pdf

Soler, J. & Miller, L. (2003) ‘The struggle for early childhood curricula: a comparison of the English Foundation Stage Curriculum, Te Wha¨riki and Reggio Emilia’, International journal of early years education, 11(1), pp. 57-67.

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I. &Taggart, B. (2004) Effective provision of pre-school education (EPPE) project: final report. London: DfES.

Urban, M. (2019) ‘The shape of things to come and what to do about Tom and

Mia: interrogating the OECD’s International Early Learning and Child Well-Being Study from an anti-colonialist perspective’, Policy futures in education, January.