Unit 3: Curriculum Planning: An Integrated Approach

Section 3.1 Introduction

Units 1 and 2 focused on philosophical and theoretical conceptualising of early learning. This unit shifts from the abstract to the concrete. You focus on applying the ideas from earlier units to a process of curriculum development. Underpinned by your vision for learning, you will consider how to apply that vision to develop long-term and short-term plans, supported by the active process of pedagogical documentation. The unit ends by focusing on ethical matters such as respecting a child’s role in the development of their curriculum, engagement with parents, and the co-construction of meaning among stakeholders.

Module Learning Outcomes Addressed in this Unit

- Outline the emerging Irish approach to pedagogy and curriculum development, situating this within a contemporary international context

- Discuss the concept of co-constructed knowledge, the role of collaboration with stakeholders and the place of various modes of reflection within this approach

- Apply this concept to recognise new ways of knowing and doing in ECEC as it concerns planning, implementing, assessing and extending the curriculum

- Examine the emerging approaches and purposes to documenting children’s learning for various audiences, including colleagues, families, relevant agencies and children themselves

Section 3.2 Learning Outcomes

Upon successful completion of this unit, and the associated activities and readings, you should demonstrate the following unit-level learning outcomes:

- Develop a vision for learning, underpinned by relevant theories, as the starting point of the curriculum development process

- Outline different stages of an early years curriculum development process

- Distinguish the essential elements of pedagogical documentation

- Identify opportunities for children to inform curriculum development with their unique knowledge, experiences and perspectives

- Situate the co-construction of knowledge, underpinning the curriculum development process, from a rights perspective

Section 3.3 The Curriculum Development Process

‘Every approach to learning presupposes a set of underlying, unquestioned assumptions about how we come to know the world’ (Elkind, 2003, p. 26). In this section of Unit 3, you will begin to pose key questions that must be considered when planning a curriculum that will scaffold children’s learning. For example, ask yourself:

- What is my image of the child as a learner?

- What is my approach to teaching and learning?

- Is this approach evident in my everyday practice?

- What evidence supports my approach?

- And therefore, is this approach evident in my curriculum planning, the processes involved in documentation, and the individual and collective reflection on practice?

3.3.1 Curriculum Development Stage 1: Creating a Vision for Learning

As an Early Years practitioner, your ability to articulate your values and vision for children’s learning will start with your knowledge of how children develop and learn. This becomes your Pedagogy for Learning, which is ‘the understanding of how learning takes place and the philosophy and practice that support that understanding of learning (Ontario Public Service, 2014). The curriculum is the content of learning. This is the information that is gathered about the children’s learning experiences (Donegal Childcare Committee Limited, 2012).

The first step in the curriculum planning process is to develop your Pedagogy for Learning. To do this, you will need to draw on the knowledges, skills and values that underpin your ability to apply theory into practice. In this module, we are framing children’s early learning from a social constructivist perspective. Therefore, we are supporting you to consider your understanding of how children learn best from this social constructive perspective. When a practitioner achieves this, it gives them focus and purpose. They can ensure that their approach to teaching and learning has a strong theoretical foundation. Their underlying philosophy, which guides their approach, is transparent, and becomes instinctively threaded through the cycle of planning, documenting and reviewing.

3.3.2 Connecting across the Educational Philosophies to Inform our

Curriculum

First you need to understand the terms constructivist, social constructivist and sociocultural theory. Once you understand these key terms, this will help you to clarify your approach to early learning. It will help you also to understand what underpins well-known curriculum models, theories, and frameworks.

Note: Refer back to Learning Activity 1.8

In terms of learning and teaching, constructivists are of the view that children learn through active engagement with their environment and material, through trial and error, the testing of theories and the development of their own ‘constructions’ or meaning from these activities. The theories of Piaget and Montessori fall under this paradigm, and so do curriculum models informed by their work (i.e. Montessori and High/Scope approaches).

Social constructivists extend this constructivist thinking to consider relationships and interactions, the social world of the child, as part of their learning processes. They view the child’s creation of knowledge as occurring through interactions, as well as the environment and materials in their world. Equally, meaning-making is personally subjective for the child and reflects their unique contexts of learning, be that the family, the home, education settings, or their community spaces, which all hold important meaning in the child’s life.

Within this socio-constructivist paradigm, we situate socio-cultural learning theories, with Vygotsky by far the best-known theorist in this area. Vygotsky viewed the culture of the child’s environment as a crucial influence in their development, alongside social relations.

Note: See Section 1.7 for more on socio-cultural theories.

Children learn and develop through relationships within their family, community and social environment. The socio-cultural understanding of learning and development is the consistent principle that connects the Aistear curriculum framework with the various educational philosophies, such as Froebel, Malaguzzi, Te Whariki and some play-based philosophies.

While the above descriptions offer a way of differentiating these ideas, ‘lived practice’ in early years settings often crosses abstract boundaries between theories. Many Montessori settings include, for example, dramatic play corners where children collectively make meaning through role-play and social interactions. A core aspect of High/Scope routine is the ‘work time’ in which children meet in activity areas in small groups, and develop repertoires, drawing on their cultural tools to interact and communicate. While the original theorists may have had a clearly-defined philosophy of learning, as our understandings advance around ‘best practice’ so too does the live application and evolution of theories in early years settings.

In the section below, you will find various aspects of early years practice that should be considered as you develop your approach to curriculum. As you work through these, aim to connect back to the perspectives outlined above.

The Active & Inquiry-based Learner

Elkind (2003) explains that both Montessori and constructivists put the child at the centre of the educational programme. These approaches emphasise the opportunity to explore, manipulate, and operate upon materials at the child’s own pace and rhythm.

Discovery learning, as used in the Steiner education approach, is an inquiry-based, constructivist learning theory. Learning takes place in problem-solving situations. Here, the learner draws on his or her own past experience and existing knowledge to discover facts and relationships and new truths to be learned (Oberski, 2011).

Reflective Point 3.1

The main activity of a constructivist approach to learning is actively solving problems. This involves exploring topics of interest, drawing conclusions, revisiting conclusions and exploring new concepts and questions.

Play

Froebel viewed self-initiated activity and play as integral to children’s learning. This is a model of thinking that reflects the social constructivist theory, where play is valued as too important to be left to chance (Curtis & O’Hagan, 2003). Therefore the relationships with the adult, environment and materials are essential to supporting children’s early learning and development.

The Te Whāriki curriculum also adopts a specific socio-cultural perspective on learning. It focuses on the social and interactive process of knowledge creation, which is integral to the inquiry approach to practice and underpins an emergent curriculum. This curriculum approach focuses on children’s widening interests and problem-solving capacities. It values play as a process of meaningful learning and recognises the importance of spontaneous play.

The Role of the Practitioner

The High/Scope approach views the child as an active participant in their own learning, learning through curiosity and active problem-solving. More contemporary approaches value the child’s involvement with people, materials, events, and ideas in a social context. The teaching strategies used require the practitioner to be responsive and in tune with children’s ideas, questions and thinking.

The Environment

From a socio-cultural perspective, children learn in context: the belief is that the environment should offer children the opportunity to actively explore, make choices and decisions and engage in meaningful experiences. Dowling (2009) discusses how effective learning requires an ‘informational environment’, which supports children’s ability to make and learn from mistakes, discover the best way of doing, and learn how to make decisions. In the Reggio approach, the environment is described as the ‘third teacher’, stressing its crucial role in children’s learning opportunities.

Reflective Point 3.2

Review the 12 Principles of Aistear in the context of the Social Constructive approach to learning.

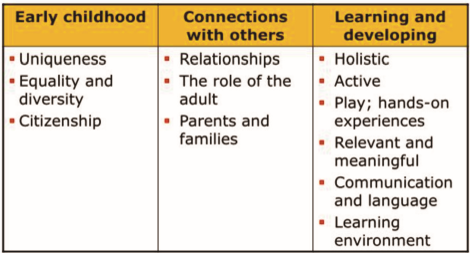

Aistear is based on 12 principles of early learning and development (NCCA, 2009). These are presented in three groups:

Aistear’s 12 principles

Learning Activity 3.1

Refer to the 12 Principles of Aistear listed above. From each group, select one Principle that you feel resonates with constructivist, social constructivist and socio-cultural perspectives on children’s early learning. Write 100 – 150 words outlining the connections between the Aistear principles you have chosen and these three perspectives on early learning. The following link may assist you in your reflections and writing.

3.3.3 From Abstract to Concrete – from Vision to Planned

The curriculum development process can often be misinterpreted as separate to our daily ongoing practice, for example it may be viewed as the large folder that contains templates or plans sitting on top of the shelf with its sole purpose of demonstrating compliance to inspectors, parents or others. From the socio-constructivist perspective, the curriculum development process should be seen as dynamic and informed by your vision for learning. It is also developed through:

- your observations of children

- your knowledge of them as active learners

- the supportive and collaborative relationships you have with the children, their families, your team

- the early years environment

- the wider community

The importance of curriculum is evident throughout the Síolta Quality Framework. Standard 7 states that planning for the child’s holistic development and learning requires the implementation of a verifiable, broad-based, documented and flexible curriculum or programme. A flexible, broad-based programme refers to all children’s learning experiences, whether they are formal, informal, planned or unplanned, which contribute to a child’s development and progression (NCCA, 2009).

Standard 8 is aligned to planning and evaluation, and states that this process requires cycles of observation, planning, action and evaluation, undertaken on a regular basis, which enriches and informs all aspects of practice (DES, 2010).

Understanding the purpose of Standards 7 and 8 will support the practitioner to understand the key components that encompass their own curriculum planning process. In other words, a flexible, broad-based programme is constructed from your observations and evaluations of planned or spontaneous activities or events that will arise from the children’s experiences, their questions and their understanding of the world.

Reflective Point 3.3

Before moving on the next stage of the curriculum development process, it is important to reflect on the key points in Stage 1 and why this stage is paramount when planning an effective curriculum.

Key points:

- Pedagogy is the philosophy or the vision for learning. It is concerned with the ‘how’. In the case of this module, we are interested in how learning happens from a social constructivist perspective.

- Pedagogy must be evidence-based and supported by a theoretical knowledge of how children learn.

- The pedagogy informs our standards and principles for practice.

- The standards and principles frame the content of a curriculum.

- Effective practice is achieved in a carefully structured and framed curriculum that has a clear Pedagogy for Learning.

Section 3.4: From Abstract to Planned to Practice

3.4.1: Curriculum Development Stage 2: Pedagogical Framing – ‘Turning Vision into Practice’

According to French (2013), pedagogical framing may be interpreted as curriculum management and organisation. It builds on your vision for learning, and involves the creation of the conditions in which children’s learning and development is enhanced. In other words, it is the ‘behind the scenes work’. It involves how you work as a practitioner:

- your approach and knowledge of how to support children’s learning,

- how you observe and assess to better understand the child and support progression,

- how you plan and resource the environment.

Pedagogical framing will include the long-, medium-, and short-term plans as well as the spontaneous plans. In other words, it is the method in which you plan, document and reflect on your curriculum.

Learning Activity 3.2

Watch this video: ‘Planning, documenting and assessing an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum’ with Dr. John Nimmo, from the Aistear Síolta Practice Guide. To access the video, use the web-link below:

http://aistearsiolta.ie/en/Planning-and-Assessing-using-Aistears-Themes/

This brings you to the Pillar: Planning and Assessing. Select the option ‘Example and Ideas for Practice’, where you will find the video as your first option.

Reflective Point 3.4

Dr. John Nimmo talks about ‘intentional planning and teaching’ and ‘interventions by the teacher’. He explains that interventions are the actions taken by the teacher/practitioner to organise what will happen next in the curriculum. These interventions may involve planning an activity, offering an intentional or particular question to the children, or perhaps adding something new to the environment. The voice of the child is depicted in the interventions which originate from the documentation of what children are saying and what they are interested in.

Learning Activity 3.3

Listen carefully to the scenario that Dr. John Nimmo describes in this video. Using the diagram below (Figure 3.1), draw out the cyclical process of planning, documenting and reflecting; now name the interventions made by the teacher/practitioner and place them in the diagram.

3.4.2 Documenting your Long-term Plan

According to NCCA (2009) the long-term plan provides a sense of purpose and direction in the curriculum being offered to children, and shows progression over time. Working within the social constructive approach underpins this clear sense of purpose by dictating that successful planning must start with the child. Working in this way, the practitioner ensures that the curriculum and environment are framed by what children know already and what is personal to them. The child is encouraged to actively pursue their questions and ideas, their early theories that lead to deeper understanding and more complex thinking where further questions can be investigated.

Learning Activity 3.4

Return to your planning cycle, developed for Learning Activity 3.3. In order to ensure that your plans are ‘framed’ by the children’s knowledge and interests, note where the child is relied on to inform the curriculum and in what ways. Some examples may include observations of children, consultations with children, reflective notes following these actions, etc. Ask yourself: how is this plan framed by what I know of the child, their interests, ideas, dispositions, and identity?

A long-term plan should be framed by

- A clearly articulated pedagogy for learning underpinned by the standards of Síolta.

- A shared understanding of how children learn in the early years and what we want for the children. This should include the children and families’ own ambitions and aspirations.

- The four themes of Aistear and the types of learning: Dispositions, Values and Attitudes, Skills, Knowledge and Understanding.

- The important celebrations that represent children’s identity, background and community.

Reflective Point 3.5

Consider how your setting documents their long-term plan. How does the long-term plan involve the children and families? Does this approach justly reflect their own goals and aspirations? What are the strategies you use to ensure it is achievable?

Learning Activity 3.5

Consult with the children and families in your setting about their goals and aspirations regarding the child’s learning and experiences in the setting. Using their words, put together a vision board that demonstrates the setting’s long-term plan.

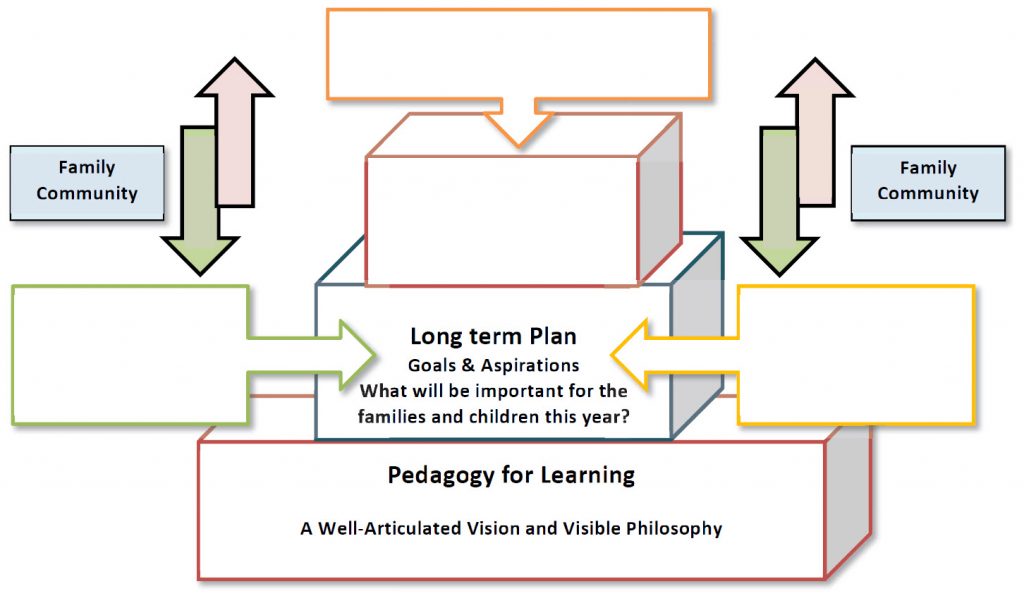

The first stage of your process of turning vision into practice is captured in Figure 3.2, depicting the Long-Term Planning process.

3.4.3 Medium- and Short-term plans

At this point in the unit, you should be able to clearly articulate your pedagogy for learning and demonstrate how this is transferred into your long-term plan. You now need to break this down into medium- and short-term planning to support children’s learning. A common barrier identified in this process is the misinterpretation and perhaps the pressure to document everything or perhaps not understanding what should be included in the medium- and short- term plans.

The medium- and short-term planning process focuses on the language, environment and activities, organised over different time-scales. Both plans should reflect the long-term plan, and should link to and follow on from each other.

Reflective Point 3.6

Refer back to the three children you met in Unit 2. In particular, let’s think about Mark. When Mark arrived at crèche today he was excited to tell about the double-decker bus he travelled on that morning. You are aware that Mark recently moved house and, reflecting on the challenges that can be posed by transitions, you want to build on Mark’s excitement and the positive aspects of the change. You add the following resources to the learning environment to support Mark’s interests:

- Provide a number of vehicles in the block area

- Add a driver’s hat and the ‘steering wheel’ frame to the dramatic play centre

- Take out some of the stories related to home, family, vehicles

- In the morning, create a few ramps and slopes in the block area

You want to accurately reflect what Mark’s interests are and what he is really excited about. You listen carefully to what Mark is saying. Together with Mark and the children, you discuss what Mark sees when he is sitting on the top deck, what are the landmarks he sees every day when he travels to crèche. You start collecting the documentation of Mark’s questions, stories and drawings.

Medium-term Plan: Using a spider diagram, you set out a broad plan for the next month/term. Your plan will focus on what Mark sees every day on his way to crèche, and together you plan to carry out a research project with Mark and all the children, focusing on chosen landmarks.

Short-term Plan: Using the Medium-term plan and your documentation with the children, you set out the first step in the plan, which will be carried out over the next week or fortnight. Together you and children decide to map, draw and cut out images of the important places they see on their way to crèche every day. To help connect the learning, you will share your plans with the families and relevant members of the community.

To help you document your medium- and short-term planning, use prompts to reflect the four themes of Aistear. These prompts include: possible questions to ask the children, relevant key words (expanding language), outings, activities, open-ended resources and upcoming events in the children’s lives and community.

Reflective Point 3.7

Review the medium- & short-term planning templates available in the Aistear Síolta Practice Guide under the Planning and Assessing Pillar – Examples for Practice http://aistearsiolta.ie/en/Planning-and-Assessing-using-Aistears-Themes/

Learning Activity 3.6

Drawing on knowledge from this and previous units/modules, create a list of key benefits for children who attend early years services before the age of 5 years. Then identify which of these benefits are likely to have a more longterm effect at ages 10, 15 and then 20 years.

3.4.4 Unplanned, Spontaneous Learning

Many of the learning activities that occur in early years settings are adult-led, or come about through adult-child collaboration, as part of the curriculum planning process. However, many learning opportunities are also the result of children’s active self-led learning. When something happens in an educational environment that is inspirational or exciting for both children and practitioners, it becomes a teachable moment, and according to Fleet et al. (2017) everyone needs to devise effective ways of working with children, to capture and build on these moments. Fleet et al. (2017) recommend that practitioners develop an accessible system that will enable you to foster the children’s ideas, theories and questions and help you intentionally plan for deeper, more complex thinking.

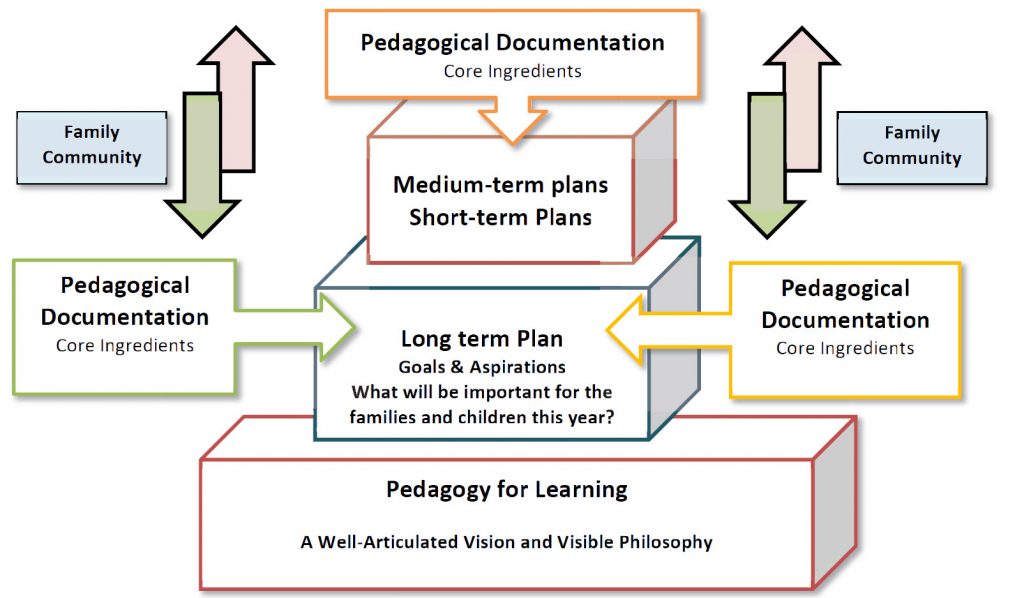

Pedagogical documentation is the tool that is used to create opportunities for collaborative learning and shared reflections, and the valuable information recorded during the pedagogical documentation process will inform the planning for future learning. Figure 3.3 depicts the full curriculum development process.

Section 3.5 Essential Elements of the Pedagogical Documentation Process

3.5.1 Stage 3: Pedagogical Documentation within the Curriculum Planning Cycle

In this section, you will examine the essential elements of the process of pedagogical documentation. These elements are skill-based and reflect your values as an Early Years Practitioner. You should regard them as integral and instinctive to your everyday practice and work with children. Therefore it is important to distinguish each element and outline their merits within the context of pedagogical documentation.

An in-depth knowledge of the core ingredients that are crucial to the pedagogical documentation process will further enrich your own philosophy for learning. Fleet et al. (2017) state that when teachers believe that pedagogical documentation is something in addition to what they do each day, rather than an opportunity to reframe their pedagogy and instead embed it, then documentation loses a certain dimension. In other words do you view writing up your notes as simply an added burden which you have to complete, instead of viewing it as a professional strategy for thinking about pedagogy? (Fleet et al., 2017, p.3).

3.5.2 Pedagogical Documentation: The Core Ingredients

Observation

The first cornerstone of documentation is observation. In the modules Psychology of the Developing Child 1 and 2, you examined in detail the different types of observations and their individual purpose.

Rather than thinking of documentation as the end of a process – the final tangible document – Pelo (2006) describes documentation as an action and activity and encourages us to construct it as a verb (documenting), rather than a noun – the document – an end product. Pelo’s view is that taking this perspective focuses the practitioners’ attention as a way of being in a relationship, and the rhythm of observation, reflection and planning in this relationship. Documentation therefore becomes an action in which you as the practitioner are drawing on your observations skills to also make children’s learning visible. Pelo (2006) discusses the cyclical nature of the pedagogical documentation process by explaining how the exploration grew step by step, through observation, reflection and study, planning and telling the story. These observations were then used to guide the planning day by day, week by week.

Pelo emphasises the importance of staying grounded in specific observations, in other words using strategies to support the practice of observation and documentation. In the examples cited, the practitioners focused their observations on the children’s play and informal conversations. In a collaborative way, the practitioners then reflect and study the observations and documentation and ask questions about what the children were curious about, or trying to figure out? What were the children’s understandings or misunderstandings, or what experience were they drawing on? These observations also draw upon the teachers’ understandings of the children’s particular lives, world views and experiences (Pelo, 2006). Subsequently, all of the information gathered gives rise to unfolding possibilities where new observations are documented, studied and incorporated into the curriculum plan, and the cycle begins again.

Let’s recap the steps recommended by Pelo (2 –6)

- Stay grounded and focused on observing particular activities.

- In collaboration, reflect on the observations; study the documentation.

- Ask probing questions to extend your knowledge of what is occurring and what is driving the children’s actions.

- Inform these deliberations with your knowledge of the children and their rich lives.

- Develop plans to extend the children’s actions, interests, emerging skills and abilities.

And the cycle continues…

Working Theories

Te Whariki defines working theories as a combination of knowledge, skills, dispositions and attitudes that contribute to children’s development of learning dispositions (Ministry of Education, 2017). Te Whariki also recognises the important role of the social constructivist approach, where children’s working theories develop in environments where they have opportunities to engage in complex thinking with others, observe, listen, participate and discuss within the context of topics and activities (Ministry of Education, 1996). Working in this way, the practitioner seeks out opportunities for children’s thoughts and ideas to plan the direction of the curriculum. This does not mean taking on a laissez faire approach. It requires skilled and flexible adults who can move between scaffolding and co-construction with learners (Jordan, 2004).

Working theories are a key outcome in Te Whariki. Their approach uses documentation to make meaning of children’s learning, and creates a shared language between the home and setting, encouraging a culture of reflective discussion. The emergent, inquiry-based curriculum recognises children’s interests as central in their dynamic learning processes. As a practitioner, you will have observed that sometimes children’s interests can be fleeting, while other interests are more considered and revisited by the children. The Te Whariki curriculum uses Claxton’s (1990) Island analogy to create a metaphor for working theories to reflect children’s sustained interest, and call these ‘islands of interest’. When the islands grow and when the learning becomes deeper and more connected, the island of interest becomes an island of expertise.

Reflective Point 3.8

Return to Mark’s story. Consider how his island of interest will grow and develop as new concepts and questions are explored and studied within a participative process.

A Participative Process

Pedagogical Documentation supports the dynamic processes and interactions related to children’s learning. Vecchi (1993) explains that documentation allows the practitioners to serve as children’s partners, sustaining children’s efforts and offering assistance, resources and strategies to get unstuck when encountering difficulties. Dewey (1934) emphasised the point that pedagogical documentation is not a direct representation of children’s ideas and understanding. Rather it is an interpretation based on close, keen observation and attentive listening to children whose thinking, saying and acting practitioners are trying to document. Pedagogical documentation can also be considered as a form of listening, and listening carries the meaning of ‘intersubjectivity’. This relates to the shared experience that emerges through a search for knowledge where practitioner and child are moving together in mutual curiosity and interest.

Possibility thinking

According to Cremin (2006), possibility thinking is a co-participative process. It is considered implicit to problem-finding and problem-solving, and therefore central to creative thinking and learning. This is considered to be an inclusive approach to pedagogy, where the practitioner passes the control back to the learner. It is learner focused. The practitioner acts as a co-researcher, using documentation that values and tracks the children’s quest as they imagine, hypothesise and persevere to solve and think through a problem. All of which supports children’s positive dispositions for learning.

Making Learning Visible

Pedagogical documentation is more than just displaying children’s work. It is part of the dynamic curriculum development process. When the practitioner devises creative ways to make the children’s learning visible, it supports the cyclical process of meaning-making, recall and reflections that influence the direction of future learning and teaching. The pedagogical documentation methods can include children’s work, drawings, photographs, powerpoint presentations, graphs, mind maps, talking books, plans and drafts of work in progress, audio / video tape recordings of children and practitioners in action or conversation, written transcripts of children’s conversations, comments, debates, questions, illustrations, child observations, portfolios and journals.

3.5.3 Ethical Documentation

The pedagogical documentation process is a method of enquiry that requires a great deal of sensitivity for children’s ideas and feelings. Therefore it is essential that practitioners are respectful of the rights of children and their families when documenting children’s learning. This includes respecting the agency and privacy of children and families, including their right not to participate and not to have documentation made public. To be ethical in your documentation means having informed consent from families and children and treating the product of documentation confidentially. This also means respecting children’s and families’ culture and language.

Janssen & Vandenbroeck (2018) reviewed parental engagement, as it is represented in various curriculum frameworks, and what this means for practice in a range of states. They question whether meaningful consultation occurs, noting the ‘subordinate’ role that can be constructed for family members in some of the contexts explored. From an ethical, democratic and rights-based perspective, Janssen & Vandenbroeck (2018) challenge practice settings to seek opportunities to coconstruct knowledge with families in meaningful ways; to shift from merely seeking parents to reinforce previously-set learning goals. They refer to the importance of ‘reciprocal negotiations with families’ (ibid, p. 16) as being more than sharing information, involving being open to collaboratively planning with families as part of the curriculum development process.

From an ethical perspective, it is important to recognise that subjective decisions are taken by practitioners in terms of what to capture and how to capture it in the documentation process. In pedagogical documentation, the practitioners are researching with children with the goal of developing and transforming curriculum, not standing at an objective distance. This ‘with’ is important: according to Fleet et al. (2017), it is an empathetic and pedagogical approach. Research conducted by Walsh (2017) examined the pedagogical documentation process, and specifically examined children’s perspectives on their experiences. Findings highlighted the importance of the child’s voice, of meaningful listening, and the impact of respectful processes on children’s sense of wellbeing.

Learning Activity 3.7

In the Learning Materials Folder on Blackboard, download the following document: Walsh (2017) Research Brief. Note the key findings and relate these to developing an ethical approach to pedagogical documentation in your practice. Develop three key recommendations.

Reflective Point 3.9

Review Figure 3.3 above to help you visualise how the process of planning and documentation are interrelated.

Consider the following questions:

a) How do you currently document children’s learning?

b) Does your pedagogical documentation inform the short-, medium- and long-term plans?

c) Does your pedagogical documentation capture spontaneous learning moments?

d) How do you reflect on and study the documentation?

e) How do you plan for the next steps in children’s learning?

f) At what points are children involved in the pedagogical documentation process?

g) At what points are family members involved?

h) How does the (children, family) involvement impact on the process?

Section 3.6 Unit Review

In Unit 3 you moved from the abstract and conceptual to the concrete and applied, particularly in regards to the curriculum planning process. Creating a vision for learning is proposed as the first crucial step in the process, which reflects the knowledges, skills and values that underpin your philosophy of early learning, or your pedagogy. Through the unit you revisited the constructivist and socio-constructivist paradigms, linking these to common curriculum approaches and frameworks in the Early Childhood Education and Care field. You explored how to apply your vision to practice, in terms of pedagogical framing, and developing long-, medium- and shortterm plans. The unit emphasised the importance of accommodating spontaneous learning opportunities. These are often child led, emerging from children’s own interests and investigations.

Section 3.7 Self-Assessment Questions

- Name key theories, any related theorists whose ideas underpin the vision for learning promoted through this unit, and any curriculum approaches they inform.

- Outline the different stages of an early years curriculum development process as outlined in this unit.

- What are the essential elements of pedagogical documentation?

- Identify ways in which children inform curriculum development process.

- How is a children’s rights perspective related to the concept of children being involved in the ‘co-construction of knowledge’?

Section 3.8 Answers to Self-Assessment Questions

- Constructivist ideas have strong connections to early childhood education and early learning approaches, and are based on the idea that knowledge creation is a dynamic process of active learning, that is influenced by the many contexts in which the child exists and the varied experiences a child has. These ideas are found in Montessori settings, High/Scope programmes, and are influenced by the ideas of Montessori and Piaget.

- Extending these ideas to place greater emphasis on the social and cultural elements of learning situates us within the ‘socio-constructivist’ paradigm. This approach includes the child and others in their social world as coconstructors of knowledge. Theorists who promote this view include Vygotsky, Froebel, Malaguzzi and Dewey. Central to this perspective is the view that children learn and develop through relationships within their family, community and social environment. The socio-cultural understanding of learning and development is the consistent principle that connects the Aistear curriculum framework with the various educational philosophies, such as Froebel, Malaguzzi, Te Whariki and some play-based philosophies.

- The different stages of the curriculum development process include establishing your ‘vision for learning’ and the follow-on pedagogical framing. Your vision is the philosophy or perspective you hold about children’s early learning and what this means for your role in that approach. Pedagogical Framing is the ‘behind the scenes work’ involving your work as a practitioner, your approach and knowledge of how to support children’s learning, how you observe and assess to better understand the child and support progression, and how you plan and resource the environment. It includes long-term, medium- and short-term planning. It also includes your approach to observing, documenting and reflecting on your curriculum, as well as ways you work with other key actors in the planning and reflection.

- The essential elements of pedagogical documentation include observation, identification of ‘working theories’, ensuring the process is participative, engaging in possibility thinking and providing documents that will give evidence to these processes, and finally, reflecting on these documents with key stakeholders.

- Children should inform the curriculum development process, in order to ensure their learning moments are meaningful to them and reflect their interests. Consulting with children at the start of the year can assist in developing long-term plans, as can consultations throughout the year, revisiting these plans, to inform medium- and short-term plans. Children should also be involved in all elements outlined above for SAQ3. In particular, reflecting on documentation with children ensures you hear from their own perspective what was meaningful, relevant and important in the moments you capture, so that you can build on those interests in your emergent planning. From a children’s rights perspective, we believe children should have a voice in matters that affect them, that their opinions are valid and should be given due weighting. From a sociological understanding of childhood, we position the child as an active agent, as a catalyst for their own learning, and as someone with will, with their own learning goals and intentions. Therefore, involving children, as set out in our response to SAQ4, above, facilitates the position that the child’s views and perspectives should inform the ongoing curriculum development process. A children’s rights perspective ensures learning activities are meaningful for the child as they reflect their genuine interests, their working theories, and extend their possibility thinking.

Section 3.9 References

Claxton, G. (1990) Teaching to learn a direction for education. London: Cassell.

Cremin, T., Burnard, P. & Craft, A. (2006) ‘Pedagogy and possibility thinking in the early years’, Thinking skills and creativity, 1(2), pp. 108-119.

Curtin, A. & O’ Hagan, C. (2003) Care and education in early education. A student’s guide to theory and practice. London: Routledge Falmer.

Department of Educational and Skills (DES)(2010) Síolta, the National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education. Dublin: Stationery Office.

Dewey, J. (1934) Art as experience. New York, NY: Minton.

Donegal Childcare Committee Limited (2012) Professional pedagogy for early childhood education. Donegal: Donegal Childcare Committee Publishing.

Dowling, M. (2009) Young children personal social & emotional development. London: Sage Publishing.

Elkind, D. (2003) ‘Montessori and constructivism’, Montessori life, 15 (1), pp. 26-29. Available at: https://search.proquest.com/openview/37d8e02701c23b63458221435790cc09/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=33245

Fleet, A., Patterson, C. & Robertson, J. (2017) Pedagogical documentation in early years Practice: seeing through multiple perspectives. London: Sage.

French, G. (2013) The place of the arts in early childhood learning and development. Commissioned paper from the Arts Council, Ireland.

Janssen, J. & Vandenbroeck, M. (2018) ‘(De)constructing parental involvement in early childhood curricular frameworks’, European early childhood education research journal. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1533703

Jordan, B. (2004) ‘Scaffolding learning and co-constructing understandings’. In Anning, A., Cullen, J. & Fleer, M. (eds.) Early childhood education: society and culture, pp.31-42. London: Sage.

Ministry of Education (2017) Te whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum. Wellington, New Zealand.

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (2009) Aistear Síolta Practice Guide. NCCA: Dublin.

Oberski, I. (2011) ‘Rudolf Steiner’s philosophy of freedom as a basis for spiritual education?’, International journal of children’s spirituality, 16(1), pp.5-17.

Ontario Public Service (2014) How does learning happen? Ontario’s pedagogy for the early years. A resource about learning through relationships for those who work with young children and their families. Ontario: Queens Printer for Ontario.

Pelo, A. (2006) ‘At the crossroads: pedagogical documentation and social justice’, Insights, Chapter 10, pp. 173-190.

Vecchi, V. (1993) ‘The role of the atelierista’, in Edwards, C., Gandini, L. & Forman, G. (eds.) The hundred languages of children: the Reggio approach to early childhood education, pp. 119-127. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

Walsh, A. (2017) Young children’s perspectives of child-teacher interactions when compiling Learning Portfolios: A case study to inform pedagogical assessment practice. Research Brief. Galway: NUI Galway.