Unit 5: Interpreting, Reflecting and Designing the Curriculum

Section 5.1 Introduction

At this point in the module, you have pieced together the essential ingredients to start the process of interpretation to help you design a curriculum that supports the children’s interests, deep inquiries and working theories. In Unit 4 you were introduced to the process of pedagogical narrations where you were asked to document a series of natural moments observed with a child or group of children in your setting. In the next stage of the cycle, you will deepen your understanding of children’s learning by studying and reflecting on the pedagogical narrations and documented moments, using multiple perspectives. Fleet et al. (2017) describe this stage as an opportunity to pose bigger questions and ideas that will enrich and progress the children’s learning. In Unit 4, pedagogical documentation was described as a verb, an active and participatory process that helps children recall and think about their thinking; however, it is also an experience that encourages the practitioner to think, reflect, review and theorise. This stage in the cycle is not about finding answers but generating questions through collaborative inquiry and dialogue, and it is this approach that is at the heart of an emergent curriculum.

Module Learning Outcomes Addressed in this Unit

- Discuss the concept of co-constructed knowledge, the role of collaboration with stakeholders and the place and various modes of reflection within this approach

- Apply this concept to recognise new ways of knowing and doing in ECEC as it concerns planning, implementing, assessing and extending the curriculum

- Outline the place of assessment of, for and as learning in Early Years contexts, and the related terminology, from theoretical and applied perspectives

- Assess and demonstrate how to appropriately structure the learning environment to challenge and enhance/enrich children’s thinking

Section 5.2 Learning Outcomes

Upon successful completion of this unit, and the associated activities and readings, you should demonstrate the following learning outcomes:

- Use pedagogical narrations as a tool for interpretation and reflection using multiple perspectives

- Interrogate the pedagogical intentions underpinning daily rituals and routines

- Explore the concepts of assessment of, assessment for and assessment as learning

- Apply the principles and practices of pedagogical documentation to plan and create an integrated early years curriculum

Section 5.3 Pedagogical Approaches in the Emergent and Inquiry-Based Curriculum

Pedagogical documentation is an integral element in the cyclical process which informs the development of an emergent curriculum. Carr (2001, p.44) suggests ‘it is about the interrelated phases of noticing, recognising, responding, recording and revisiting’. This is pedagogical framing in action. It involves a skilled approach, drawing on knowledge, reflection and understanding, but more importantly, the delicate balance of attention given to children’s learning and the practitioner’s teaching (Fleet et al., 2017).

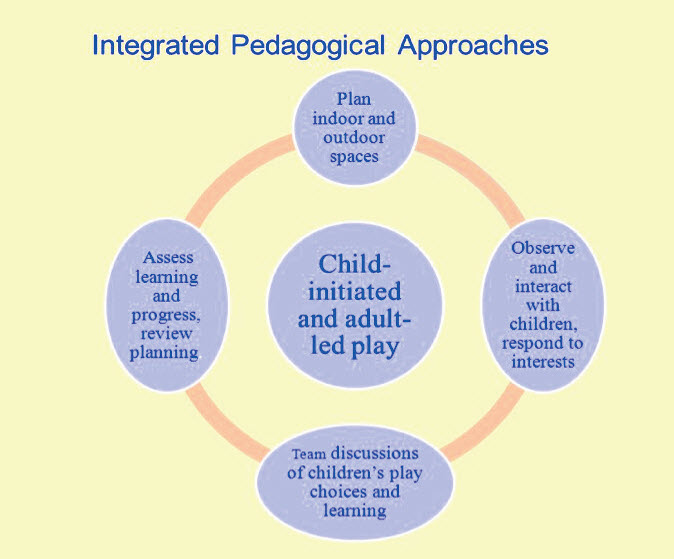

As discussed in previous units, the need to find a balance between adult-initiated activities and child-initiated activities, and to be aware of the meaning of both, is central to developing an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum. This awareness focuses the practitioner on what role they play in children’s learning; it means understanding the difference between adult- and child-initiated learning. Walsh et al. (2010) discuss the idea of play as the characteristic of child-initiated and adultinitiated activities. In adult-initiated activities, the practitioner takes a focused approach through playful and experiential activities. In a child-initiated activity, the child chooses what to do, how to do it and with whom to do it. Both require the practitioner to be flexible and to look for opportunities to support emerging ‘working theories’ and skills in the child, or to scaffold their learning. Providing the time and opportunity to respond to and allow for children to discover and explore is crucial in this approach. Wood (2007) explains that pre-planned intentional activities can have a playful orientation, where the practitioner can respond to children’s play activities by extending their interests. In other instances, the children are given the opportunity to choose and engage in ‘pure play’ where the children are able to practise intrinsic motivation, internal control and autonomy. Before the processes of interpreting, reflecting and planning occur, consideration must be given to the intentional teaching strategies adopted and how these strategies influence the important data – the results of the documentation process – that you hold in your hands.

5.3.1 Stages of a Practitioner’s Development in Pedagogical Documentation

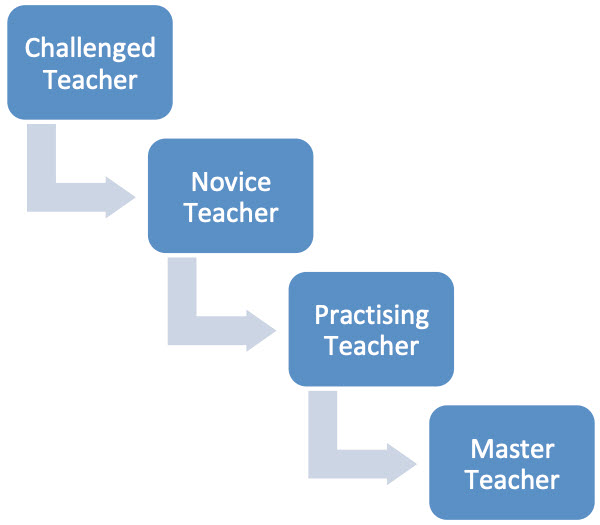

Wien (2008, in Lim, 2016) suggests four stages (see Figure 5.1) of a practitioner’s development, as they become more adept at the processes involved in pedagogical documentation in an emergent curriculum:

- The challenged teacher likes the idea of emergent curriculum but they don’t know how to do this.

- The novice teacher of emergent curriculum can collect artefacts, take pictures, and observe/record some excited moments, but they struggle withhow to discuss with children for learning, and how to connect children’s ideas to meaningful learning. The novice teacher feels documentation is extra work they have to do. However, they know documentation is a powerful tool to communicate with parents and that children love looking at themselves through documentation.

- The practising teacher knows how to have a conversation with children that reveals their ideas and theories, making these visible through documentation. They are unsure about how documentation and the everyday classroom activities are connected. They feel that practical collaborative meetings are needed to share their classroom episodes or documentation and their thinking, instead of limited staff meetings. Also they observe their environment to assess how it shapes the children’s behaviour and they can correct something that isn’t functioning well, however they just focus on physical environment such as materials, and quantity of choices available.

- The master teacher brings their own thinking and inquiry into children’s learning; they re-organise and interpret what they observe, and reflect on this. Working collaboratively, they enjoy different interpretations that widen their thinking and working together by dividing roles systemically. Their classrooms are open at all times, to actively facilitate communication with parents and the wider community. They don’t document everything in the classroom. They can decide really carefully what to document, and it’s connected to what they’re studying. They plan multiple layers into the day for giving possibilities to children and themselves (Wien, 2008).

(as they become more confident in their own engagement with an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum)

Reflective Point 5.1

Reflect on the four stages of practitioner development and consider what stage you are presently at in the development of your skills and knowledge in the documentation process. This is a strengths-based activity to help you identify your present capacities, your knowledge and understanding, of the key principles involved in this approach. It is important that you perceive the habit of documenting and visual literacy as a gradual process which develops over time.

5.3.2 Daily Routines and Rituals as Part of the Curriculum

Aistear defines curriculum as ‘the whole programme offered to children’ …. as ‘All experiences – formal, informal, planned and unplanned in the indoor and outdoor environment, which contribute to children’s learning and development’ (NCCA, 2009). Therefore, when thinking about how we engage with an emergent and inquirybased curriculum, we need to also consider the routines and rituals, including transition periods, within our programme, from this pedagogical perspective.

For some of these events, such as circle-time, small-group activities, an outing, for example, you may come to them from an adult-initiated position, where you have goals for the activity, linked to your planning cycle (long-, medium-, short-term). Other activities may present opportunities for spontaneous learning moments, that are more likely to be child-initiated, potentially providing a rich ground for you to observe, and make quick notes you may come back to later in the day, to build plans around. These times may be snack or other meal times, transitions such as getting ready for outdoor play, hand-washing before or after snacks, messy play or time in the outdoors.

These periods of ritual are ideal times for listening, observing, documentation and thinking about the child, learning about their interests, their ideas and working theories, seeing how they express themselves and possibly bring their funds of knowledge to their story telling, in a different context than amid other busier times in the day.

Learning Activity 5.1

Reflect on the circle-time routine in your setting. Define the pedagogical approach during this routine. Think about how circle-time is planned and the learning intention? Are the activities directed by the practitioner? What role do the children have at circle-time? Does the circle-time routine reflect your vision for learning?

5.3.3 Interactions as Part of the Curriculum

Speaking at an international policy event in Dublin in 2015, Prof Melhuish, of the University of London, who was involved in the initial EPPE study, as well as the followon studies, asked the question ‘What matters in the quality of early childhood education and care?’ His clear and direct response: Interactions drive development.

Building on our thinking about routines and rituals as part of the emergent and inquirybased curriculum, we need also to think about the intentionality underpinning our ongoing interactions and how we may, or may not, harness these to underpin our curriculum.

Note: You can view Melhuish’s lecture here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2U1zoC6EUbw

Learning Activity 5.2

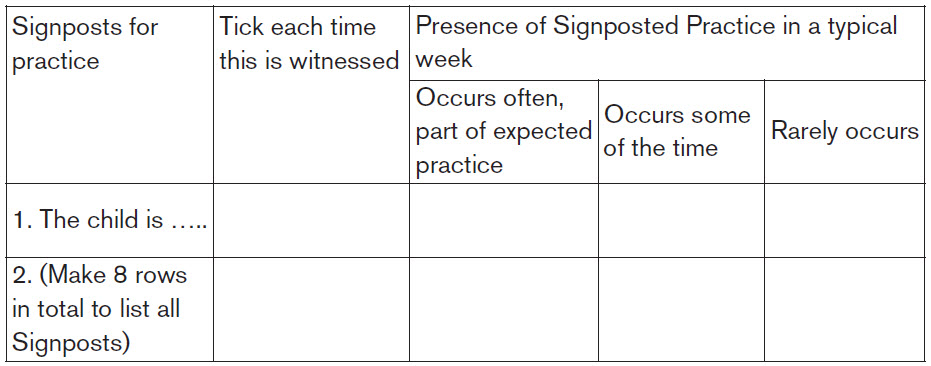

Assess the quality and frequency of interactions with children in your setting, in support of developing an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum.

Refer back to Learning Activity 4.1, where you accessed the Department of Education’s Guide to Early Years Focused Inspections.

Refer to Appendix 1: Quality Framework for EYEI incorporating Signposts for Practice. Go to Area 2, Quality of processes to support children’s learning and development; Outcome Six, High quality interactions with children are facilitated.

Create a table using the eight Signposts for Practice, listed under Outcome Six, to organise your rows; label your columns with the following headings:

If possible, recruit a supportive colleague that you work with, to engage with you in this peer-learning activity. Together, look over the eight ‘signposts’ and predict how common you believe these behaviours are in your practice; are these new ideas or behaviours you are familiar with and expect of yourself?

Over the course of a week, simply use check marks to indicate each time the behaviour described under each of the eight signposted practices occurs (second column); you observe and track your peer, your peer observes/tracks you. It will work best to do this on a daily basis, throughout the week. At the end of the week, meet up to review, discuss and evaluate your practices: use the following three columns to assess the presence of the promoted practices in a typical week.

Think about adult-initiated activities, child-initiated activities and spontaneous activities. Be sure to consider your daily routines and rituals, including regular transitions and other parts of your day.

Was the outcome surprising? Validating? Challenging to you?

Section 5.4 The Relationship between Pedagogical Documentation and Assessment

Pedagogical documentation provides the important evidence of children’s learning – your ‘data’. Fleet et al. (2017) describe the process of pedagogical documentation as an ethical and subjective means of assessing what children know and understand, in contrast to a process of measuring and judging in line with an acceptable standard. Moss et al. (2008) explain how ‘pedagogical documentation plays a role in seeing and understanding children as individuals rather than normalising children against standardised measures’. In the Irish context, the practitioner uses the aims and learning goals in the four themes of Aistear to interpret and build on children’s experiences. Pedagogical documentation is particularly helpful in showing and understanding the children’s interests, dispositions, abilities, knowledge and strengths.

Wood and Hedges (2016) discuss how specifying outcomes and related assessment approaches in curricular documents runs the risk of creating the default pedagogical position of formal/didactic approaches. In contrast, building a curriculum around working theories allows for content to be addressed in more creative and responsive ways.

There are three main types of assessment approaches

Assessment of learning and development historically has been the most common form of assessment and is normally associated with standardised testing. It is the assessment of a child’s learning at a particular point in time (Flottman, 2011).

Assessment for learning: early childhood professionals gather evidence of children’s learning and development, based on what they write, draw, make, say and do. They analyse this evidence and make inferences from it by applying their knowledge of child development theory, the child’s social and cultural background and their knowledge. According to Navarrete (2015) documentation adds to formative assessment by creating the opportunity for practitioners to have a richer understanding of children’s holistic development.

Assessment as learning and development occurs when the child is involved in the assessment process. Through this process, the child has the opportunity to monitor what they are learning and use feedback to make adjustments to their understandings (Earl, 2003).

Reflective Point 5.2

A fourth understanding of assessment is ‘dynamic assessment’. This approach to assessment is derived from Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and the zone of proximal development concept. Dynamic assessment requires practitioners to observe the things that children can do and to respond to these to help children progress to their next level of development. Ozgur & Kantar (n.d.) state that the aim of dynamic assessment is to assess the potential for learning, rather than a static level of achievement. It does this by prompting, cueing or mediating within the assessment, and evaluating the enhanced performance, for example ‘is there another way to do this?’ This is a reflective question that practitioners use in this context to establish and scaffold the children’s understanding and problem-solving to help develop new thinking.

Reflective Point 5.3

Think about a time in your life when you learned a new skill. How did you learn this skill and who supported you in the learning process? How were you supported and what made the difference to you as the learner?

When you are using pedagogical documentation as a means for assessment, it acknowledges the socio-cultural context in the assessment process and recognises that children’s learning and development is dynamic and ongoing. It is also dependent on your skills and understandings as a knowledgeable practitioner and therefore it is expected that you take account of the following:

- What is known about child development and learning (e.g., knowledge of age-related characteristics, the stages of play, schematic learning and appropriate teaching strategies)

- What is known about each child as an individual (e.g., knowledge based on observation and assessment that enables the teacher to adapt and be responsive to that individual variation). Reflect back to Unit 2 and what you know and understand about a child’s Multiple Identities.

- What is known about the social and cultural contexts in which children live (i.e. the values and conventions of each child’s family and community). Reflect back to Unit 2 and what you know and understand about the Funds of Knowledge.

(Adapted from NAEYC, 2009)

Dunphy (2010) discusses how the practitioner must have an extensive understanding of early learning and knowledge of the important areas of learning, such as literacy and mathematical concepts, and knowledge of how to make these accessible to even the youngest children. Integrated early literacy and mathematical thinking will be discussed in more detail in Unit 6.

One of the primary goals of early childhood education is to foster a love for learning through nurturing children’s positive dispositions, skills, attitudes, knowledge and understanding. In Unit 3, you looked at what you will include in your long-term plan. Together with the families and the children, you will set out goals and aspirations for the year ahead using these key areas to inform the discussion.

Reflective Point 5.4

Let’s think about these concepts – dispositions, capacities and skills, positive attitudes, knowledge and understanding – in terms of assisting us to come to know the children in our settings. How do these concepts help us in understanding where the children are, their strengths and areas that may need support to develop. The following examples are not a tick-box approach when assessing children’s achievements, rather they are areas you might consider in thinking about how you might best work with each child. When thinking about these concepts, base your perceptions on what is known and what is important to each child and their lived experiences.

| Dispositions

Confidence, Initiative, Purposefulness, Perseverance, Concentration, Resourcefulness, Curiosity, Self-control, Imagination, Determination, Resilience, Motivated, Independence, Having fun |

| Capacities & Skills

Social abilities, Communication skills, Listening skills, Using language, Problem solving,Negotiating skills, Technical, Manipulating objects, Balancing, Climbing, Mixing/pouring, Crawling, Running, Hopping , Throwing , Holding, Cutting |

| Positive Attitude

Copes with frustration – Responsible for self-care and respect towards others; Shows initiative – Takes risks, Tries out new things, Investigates; Demonstrates empathy and responsibility – Explores and learns to care for the natural environment; Embraces challenge and change, Is Motivated and Purposeful |

Note: Edwards and Gandini (2001) describe how pedagogical documentation is instrumental in promoting the learner’s self-confidence and self-awareness. When children are involved in reflecting and interpreting documentation, you are creating an opportunity in which they are able to recognise themselves as a learner and develop a positive self-image.

|

Knowledge and Understanding Expressing feelings, Sharing information with others, Expressing creatively/imaginatively, Asking questions, predicting and justifying, Understanding pictures and symbols Responding to music, stories and drama, Counting, classifying, Ordering, and Sizing, Showing awareness of space, size, pattern. Understanding rules, Showing an understanding of who they are and understanding the world around them |

Note: According to Grissmer et al. (2010), understanding the world around them is one of the strongest predictors of young children’s later science learning and reading, and a significant predictor of mathematics.

Adapted from NCCA (2009) Aistear Siolta Practice Guide: Helping Young Children Develop Positive Dispositions for Learning: Tip Sheet and Donegal Childcare Committee Ltd (2012).

When we think of ‘assessment’, there is a tendency to think of pass or fail, of scoring, of seeing what is lacking. Through this unit, you are asked to ‘de-construct’ that notion of assessment and think instead about the concept of ‘understanding’. In an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum, assessment is merely a process of coming to understand where the child is at, what are their strengths, what areas need our support, when to step up and when to stand back when working with the child, and basing our assessment on each child’s unique individuality.

Learning Activity 5.3

Watch the video available on Blackboard: Pedagogical Documentation – Making Children’s Learning and Thinking Visible, by Professor Carol Wien. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZfLUBDInAg

In the video, Professor Carol Wien speaks about children’s capacities. She gives an example of a child exploring and learning about informal physics in his play. This living moment was captured by a sequence of photographs taken over two days. Try this approach out in your own practice. Take a series of photographs that tell a story of a child’s investigation.

Make notes on the process, the outcome, and what you learned about the child’s capacities.

Section 5.5 Engaging Multiple Perspectives: Coming Together to Interpret and Reflect

Pedagogical documentation is an avenue for meaning-making and informing the development and direction of the curriculum. According to Wien et al. (2011, p.2), in this stage of curriculum design, practitioners can use pedagogical documentation to:

- imagine or theorise understanding

- present evidence of what they think they see

- check [this] against others’ analysis and interpretations

- [use these reflections, theories and interpretations to] inform their decisions about what to offer children

(Wien et al., 2011, p. 3)

Good pedagogical practice involves collecting multiple perspectives through open dialogue and inviting questions from children, colleagues, parents and members of the community, exploring different interpretations and ways of seeing. These processes also inform our assessment, of, for and as learning, through the emergent and inquiry approach. Atkinson (2012, drawing from Government of British Columbia, 2008) suggests that in these shared reflections, you challenge yourself as the educator to ‘think differently about what might be possible.’ Clark (2005) uses the term ‘multiple listening’ to describe this important process of shared reflection and interpretation; this is about creating space for the ‘other’ and recognising multiple listening as an ethical issue. The Mosaic Approach uses the purposeful strategy of multiple listening, that allows time and space for children to reflect on their experience and ideas with their peers and adults.

Learning Activity 5.4

Read the chapter by Alison Clark (2005) Ways of seeing: using the Mosaic approach to listen to young children’s perspectives: http://learningaway.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/RL56-Extract-the-Mosaic-Approach-EARLY-YEARS.pdf

It is important to develop strategies and allow for time that will support collaborative reflection. Using provoking questions about what you are seeing in the documentation evokes possibilities for new pathways of learning across the different curricular areas.

Creating a Collaborative Dialogue: Questions to Consider

- What do I want to find out about who this child is?

- What is the inquiry? What is the child questioning? What is the child’s working theory/ Island of interest?

- What does the child know already?

- What is the stage of play?

- What have we noticed about how the child is using the environment?

- How have our conversations with families helped us learn more about the child?

- How will I extend on what I’ve discovered and know about this child?

- How will we build on the child’s resourcefulness within our environment?

- How have my ‘everyday’ conversations with families given me inspiration to plan and respond to children?

- How have I used the standards and principles of Síolta and Aistear to support this child’s learning?

The following questions are useful prompts to ensure we intentionally come to our practice, that our vision for learning is present, and that we interrogate our actions to reflect that vision. Inspired by Rolfe et al. (2001) Kashin (2017) explains how the questions in the framework serve as a guide for reflection; the second and third questions are reflective and interpretative and together support the process of meaning-making.

What? This is an objective question that asks you to describe what you saw or heard.

What about the What? This is a reflective question that asks you to consider why you choose to record and document a particular situation. How did it make you feel? As you examine the documentation what makes you smile or what tugs at your heartstrings?

So What? This is an interpretative question. What are you learning about the child’s learning processes and what are you learning about your own teaching? How does this situation connect to the child’s prior experience or knowledge? How does it connect to your prior experience or knowledge?

Now What? This is a decision question. Where will you go next? How will this inform your practice? How will you use your knowledge/experience to plan for the children’s indoor and outdoor play experiences or to plan for a long-term project investigation?

Reflective Point 5.5

When attention is given to the thoughtful display of your pedagogical narrations, it creates the opportunity for multiple perspectives and interpretations from parents, siblings, children and members of the community.

Learning Activity 5.5

Watch the webinar: Pedagogical Documentation – Standards Matter, available on Blackboard. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y-iygDR49d0

Write 150 words that summarise the key learning points from this presentation.

Before moving on from this section, it is important to reflect on the interrelationship between interpretation, reflection and assessment. Assessment is about your knowledge, your understanding of how children learn and develop. However, to ensure that you do not underestimate the complexity and depth of children’s learning and what they are processing, you must reflect a disposition of not presuming to know. This requires asking how the learning is occurring and not making assumptions. This is the delicate balance of bringing together your knowledge of how children learn and a pedagogical approach that involves collective interpretations, reflection and questions which will enable you to look deeper and unfold the hidden curriculum.

The Hidden Curriculum: Looking Deeper

In the sections above, you were asked to consider daily routines and rituals, your ongoing interactions with children, as aspects of the curriculum. Further, you examined the ways in which you collaborate with others and the reflective processes you engage with, as processes that underpin your ongoing curriculum development. The notion of the hidden curriculum is another aspect to consider. It is a powerful way to think about the richness of what is occurring in your setting, on a daily basis, that you may otherwise overlook.

Fleet et al. (2017) describe a case example of two children playing together in the sandpit, in a scenario that was named Philosophy in the sandpit. In their play, the two children explore the subject of death and going to heaven. The practitioner reflects on this scenario and speaks about how frequently children’s meaning-making is invisible, and that so much of what children learn is never formally taught. Recall children’s funds of knowledge, the information they ‘collect’ in their daily lived experiences (Unit 2) or the ‘raw material’ of their experiences and interests (see Dewey, Unit 1), simply waiting for opportunities to be expressed. This is why looking deeper, questioning and listening is paramount. The way in which you use pedagogical documentation can support this all-important process. Children’s working theories and inquires will sometimes challenge the boundaries of what may be considered acceptable to talk about and to explore in the curriculum. This is a responsibility that requires a pedagogical approach where personal and professional values are examined, where multiple perspectives are considered, where sharing and learning from each other is an inherent aspect of practice, and where confident, respectful relationships with families allow for the exploration of possibly challenging topics.

Learning Activity 5.6

Watch the video available on Blackboard: Pedagogical documentation: looking deeper, an ongoing practice of making connections with children’s learning, an interview with Professor Carol Wien. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyLpxMNbd-8

Collaborative Dialogue and Reflection: Engaging Multiple Perspectives

- Set time aside to reflect with the relevant practitioners in your setting to interpret the pedagogical narrations and documented moments you recorded in Unit 4.

- Create opportunities in the routine and the environment for children and parents to contribute their ideas, questions and understandings of these documented moments.

Negotiation in the Playroom

In recent weeks, the practitioners have noticed that the construction area has become an important space in the children’s play. A group of children aged between 3.5 and 4 years have started lining up the blocks to represent a road. The children have further extended their play to building garages, houses and shops beside the road. Two of the younger children aged 2 ½ years are also enjoying this space. The practitioners have noticed that their play agenda is more focused on crashing and driving the cars into and off the roads. The different play agendas have been a source of conflict between the two groups of children.

Learning Activity 5.7

Reflect on the scenario and write a response based on the queries below:

- Who should be involved in the collaborative dialogue and inquiry?

- Deepening your thinking: How can the practitioner use this observation as a teachable moment to support the children’s feelings and understandings around the concept of fairness and personal space?

Reflective Point 5.6

Revisit Mark’s story in Unit 3. Looking deeper into Mark’s story, we know that Mark has recently moved house. The key person recognises that routine and knowing what happens next is very important to Mark at this time in his life. Reflect on how the medium- and short-term planning in Unit 3 supports Mark and his family during this time of transition.

Section 5.6 From Inquiry to Planning: Building the Pathways for Future Learning

In this section of the unit, you will examine how children’s inquiries are acknowledged through the process of pedagogical documentation, and used to plan for children’s learning and progression. As you read through these two scenarios, aim to make connections to the concepts, processes and theories you explored through this module.

Exploring Textiles

Fleet et al. (2017) describe the process of pedagogical narrations within a textile inquiry that took place over one year. The project started with children’s curiosity about textiles, it was a journey of the unknown, where the practitioner did not have an outcome and did not know how the project would unfold. Out of this inquiry, stories were documented which involved mounted photographs of the inquirymoments on the walls and tables where the project was taking place. The children’s creations were also put on display and single words were printed out, for example ‘entanglement’, ‘knots’, ‘connection’, written beside the photographs and textilebased creations. Quotes were also included as the project developed. Video clips of project moments were also documented. The indoor and outdoor environment was used to enable the children to experiment in big ways; draping and stretching the textiles where children could climb under and over. The children also experimented in smaller, more detailed ways, by sewing and stitching. This exploration led to deeper investigation and questions about where the materials came from and how they were produced. It resulted in a collaborative journey of research and reading about cotton growth and production. The project also explored the history of a traditionally feminine and undervalued ‘craft’ as well as the subject of beauty and fashion which were debated and discussed amongst the children and practitioners.

Reflective Point 5.7

What were some of the concepts that you connected with through this story? Perhaps some of the following:

- Child-initiated learning

- Participatory activity – children’s ideas and interests were valued and respected

- ‘Whole of the curriculum’ in how the textile activities ‘infiltrated’ all areas of the setting

- Possibility Thinking

- Making Children’s Thinking Visible: Pedagogical Documentation & Visual Literacy

- The use of space: Planning across the indoor and outdoor learning environment

- The integrated use of Digital Technology, Traditional Materials and Textures

- Expanding children’s language and learning new skills

- Collaborative Inquiry, Research, Reflection and Planning for ‘What happens if we do this’

- The Hidden Curriculum

Reflective Point 5.8

Thinking about assessing children’s learning, reflect on this scenario. In what ways might you draw on what is happening to make assessments of learning, for learning and to consider assessment as learning?

Aimee’s Working Theory

Aimee is three years old and she attends preschool. In recent weeks she has been learning about what makes everyone special in an ‘All About Me’ project. In the project, the children have been exploring and talking about what they have in common with each other and what makes each of them different and unique. Aimee has started to question this concept and is trying to make sense of what difference means in everyday life. She has started to make connections with what she knows already and is now applying her understanding of what difference means in another context. One day Aimee was looking at a book about insects and started to explain out loud her hypothesis. ‘A wasp and a bee kinda look the same but it is important to know they are different because a bee is good and not really dangerous but a wasp is.’ The practitioner responded to Aimee’s statement, ‘you know a lot about bees and wasps, you are right they might look the same but they are different, and you are saying that we need to know why they are different.’ This conversation presented the practitioner with the opportunity to follow Aimee’s working theory. Together, Aimee and the practitioner created an interest book to display in the book area. Aimee cut out images of bees and wasps from magazines and her questions, key words and investigations were documented and written into the book. Aimee and her peers took ownership over the interest book and it evolved over time where the concept of same and difference was explored and investigated. At circle-time the practitioner intentionally introduced other animals that look the same, such as the alligator and crocodile, the rat and the mouse and the turtle and tortoise, and together the children and practitioner researched what made these animals different from each other. This project continued for many weeks and the children created characters and stories around their favourite animals. The practitioner also observed the children play out scenarios during the free-play session where they explored and consolidated their new knowledge about these animals.

Reflective Point 5.9

What were some of the concepts that you connected with through this story? Perhaps some of the following:

- Adult-initiated learning

- Observation, valuing and responding to what children know already

- Reflective and responsive questioning used by the practitioner

- Working Theory

- Peer Learning

- Making the children’s thinking visible: Pedagogical Documentation & Visual Literacy

- The Hidden Curriculum

- Planning and Extending children’s interests and thinking

- The Learning Environment and Resources

- Time and opportunities to play and make sense of the world around them

- Understanding children’s learning, knowledge and reasoning

Reflective Point 5.10

Thinking about assessing children’s learning, reflect on this scenario. In what ways might you draw on what is happening to make assessments of learning, for learning and to consider assessment as learning?

Learning Activity 5.8

View this video: Play: Preschooler and Toddler Building with Blocks. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3f3rOz0NzPc

Discuss the following:

- In your role as practitioner, what did you focus on when you were watching this video?

Just as we did for the two scenarios given above, as you view this video, make connections to the concepts, theories, processes, and elements related to the development of an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum. Think about pedagogical narration, about collaboration and reflection and about assessment.

Reflective Point 5.11

These examples demonstrate the varying pedagogical approaches used in an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum. The practitioner may be working with an intention or perhaps it is the unknown, but it is the relational pedagogy that is clearly evident in all of the above examples that allows for possibility thinking, shared experiences and learning (See Figure 5.2).

Source: Elizabeth Wood (2009).

Section 5.7 Harnessing the Environment to Develop your Curriculum

In the Reggio Emilia approach, the environment is described as the third teacher and provocations in the environment are used to provoke questions, creative ideas and discussion. A provocation is set up in consultation with the children and it may involve an open-ended or sensory material that will encourage exploration that will expand on the children’s project or an ongoing investigation.

Learning Activity 5.9

To help you understand how the learning environment and provocations are used to expand children’s thinking and investigations, access the following resources:

• Children and place: Reggio Emilia’s environment as third teacher by Wilson & Ellis (2009): https://www-tandfonline-com.libgate.library.nuigalway.ie/doi/pdf/10.1080/00405840709336547?needAccess=true

• Watch the video: ‘Thoughtful, intentional, provocations in FDK’. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CCb2KD6X8BU

Reflective Point 5.12

- The availability of the documentation books, these are ‘living documents’ that are used to encourage the important people in children’s lives to add their perspectives.

- The provocations derived from children’s working theories are designed to stimulate further inquiries and deeper investigation.

- Choice and availability: The children are able to choose from a variety of different materials and loose parts to represent their knowledge and experiences. The children are then able to understand the transformative effects they have on materials and the transformative effects the materials have on them (Wood, 2018).

- The Emotional Environment: An environment where children feel safe and comfortable to try new things and to learn through trial and error.

Learning Activity 5.10

In collaboration with another colleague in your setting, carry out an evaluation of the indoor and outdoor environment using the ‘Creating and Using the Learning Environment: Self-evaluation tool’ in the Aistear Síolta Practice Guide under the Pillar: Learning Environment.

http://www.aistearsiolta.ie/en/Creating-And-Using-The-LearningEnvironment/

Consider the Emotional Environment and reflect on how the indoor and outdoor environment support the children to feel comfortable to experience and try new things in a safe way.

Planning and Designing

You will now begin to put all the pieces together from your documentation and collective interpretations and reflections. Using this information, you can set out ideas for further investigation and thinking in your planning and work with children.

To help you plan, use the short- and medium-term planning templates available in the Aistear, Síolta Practice Guide, under Pillar: Planning and Assessing: Resources for Sharing http://www.aistearsiolta.ie/en/Planningand-Assessing-using-Aistears-Themes/

Reflective Point 5.13

At this stage in the module, you are confident in knowing that there is no right or wrong when documenting the curriculum plan when the pedagogical approach reflects the image of the child. It is a document that demonstrates what is relevant and important to the children in the setting at that time. Jones (2012, p.67) explains that an emergent curriculum depends on teacher initiative and intrinsic motivation. It arises from the play of children and the play of teachers. It is co-constructed by the children and the adults and the environment itself. To develop curriculum in depth, adults must notice children’s questions and invent ways to extend them, document what happens, and invent more questions.

Section 5.8 Unit Review

This unit has focused on your actions as an early years practitioner, as you develop an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum and as you develop your skills and knowledge alongside this process. Through your engagement with the unit, you considered various aspects of your practice, such as the importance of daily routines and rituals, interactions that occur in your setting, and how these can be used to underpin your developing curriculum. You were asked to consider the concept of assessment in ECEC. Traditionally, assessment is constructed as a process of testing, of passing or failing. But within an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum, assessment is a collaborative, progressive approach to understanding children’s dispositions, skills and capacities, their attitude and knowledge and understanding, in order to inform the curriculum planning. Assessment can be of learning, for learning or as learning, in which young children themselves are actively involved in describing and interpreting their own learning moments. It is important to involve key stakeholders – children, family, fellow practitioners – in the process of interpreting documentation or other data created to evidence children’s learning. This ensures you gather multiple perspectives of the meaning of the data. You can feed these back in to your curriculum plans, supporting an ethical approach to interpreting, reflecting and designing the curriculum.

Section 5.9 Self-Assessment Questions

- This unit refers to the use of ‘multiple perspectives’ as part of pedagogical interpretation and reflection. What does the concept ‘multiple perspectives’ mean?

- Why is it important to think about daily routines and rituals in terms of your vision for learning and approach to your curriculum planning?

- Describe the following terms: assessment of learning, assessment for learning and assessment as learning.

- According to Wien (2008), what are the four stages of practitioners’ development, and why is it helpful to consider your development in this way?

Section 5.10 Answers to Self-Assessment Questions

- Multiple Perspectives refers to the different understandings or meaning various stakeholders will ascribe to the ‘data’ (the documents or other tangible representations of children’s learning moments) produced through the process of pedagogical documentation. In order to genuinely ‘coconstruct’ knowledge and meaning, discussions with those who are relevant to the documentation process – the child, other children, family members and other practitioners – should be consulted about what they understand the data to mean. Their views will provide you with multiple perspectives on the meaning of the data. These perspectives should feed in to your ongoing curriculum planning to ensure you approach this process in an ethical manner.

- The vision for learning (see Unit 3) you develop underpins your approach to practice, which is articulated in your curriculum. According to Aistear (NCCA, 2009) the curriculum is the ‘whole of the programme offered to children’ and this should be reflected in all aspects of the service. Daily routines and rituals, such as snack time, circle-time, even times where you are focused on transitions (lining up, dressing in/out of outdoor clothing, washing hands before/after meals or toilet practices) are all times in which children’s ideas, interests, and working theories, can be expressed by children and therefore, observed by you. These are also times of meaningful interactions between adults and children, among children and between adults such as with fellow practitioners or with family members. The manner, quality, intent and frequency of interactions and the understanding of and approach to daily routines and rituals are all areas that can underpin the development and delivery of an emergent and inquiry-based curriculum. They reveal profound moments of learning in children and provide opportunities for you to witness this learning.

- Pedagogical documentation provides important evidence of children’s early learning. You can use these to assess children’s progress and to plan for future learning opportunities within your programme. Assessment of learning provides a point in time perspective of how a child is developing, what skills they have accrued, and highlights areas that need attention and support. Assessment for learning reflects an emergent approach to early years practice, where evidence of a child’s learning and development is analysed and used to plan opportunities to support their ongoing progress. Assessment as learning occurs when the child is involved in the assessment process, sharing their own understanding of their learning moments, through the respectful and ethical practice of adults.

- Wien (2008) describes how practitioners develop along a process or continuum, as they begin to work with pedagogical documentation in an emergent curriculum. The four stages are: the challenged teacher, the novice teacher, the practising teacher, and the master teacher. It is helpful to consider your development as a continuum, as it recognises that you do not develop a new approach to your practice immediately, that this doesn’t happen overnight. It takes time to understand the underpinning ideas within an emergent curriculum, time to reflect, to develop effective team-working and to become confident and comfortable with this new approach. It also recognises that we are always learning and developing as practitioners in the early childhood education field.

Section 5.11 References

Atkinson, K. (2012) ‘Pedagogical narration: what’s it all about? An introduction to the process of using pedagogical narration in practice’, Early childhood educator, 27, pp. 3 -7. Available at: http://www.jbccs.org/uploads/1/8/6/0/18606224/pedagogical_narration.pdf

Carr, M. (2001) Assessment in early childhood settings: learning stories. London: Paul Chapman.

Clark, A. (2005) ‘Ways of seeing: using the Mosaic approach to listen to young children’s perspectives’, in Clark, A., Kjørholt, A. & Moss, P. (eds.) Beyond listening: children’s perspectives on early childhood services. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 29-49.

Department of Education and Skills (2018) A Guide to Early Years Education Inspection (EYEI) Inspectorate Department of Education and Skills Quality Framework: The Inspectorate Department of Education and Skills.

Donegal Childcare Committee Limited (2012) Professional pedagogy for early childhood education. Donegal: Donegal Childcare Committee Publishing.

Dunphy, E. (2010) ‘Assessing early learning through formative assessment: key issues and considerations’, Irish educational studies, 29(1), pp. 41-56.

Earl, L. (2003) Assessment as learning: using classroom assessment to maximise student learning. Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Edwards, C.P. & Gandini, L. (eds.) (2001) Bambini: The Italian approach to infant/toddler care. New York: Teachers College Press.

Fleet, A., Patterson, C. & Robertson, J. (2017) Pedagogical documentation in early years practice. Seeing through multiple perspectives. London: Sage.

Flottman, R., Steward, L. & Tayler, C. (2011) Victorian early years learning and development framework evidence paper. Practice Principle 7: Assessment for learning and development, Melbourne Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

Government of British Columbia (2008) British Columbia Early Learning

Framework. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Children and Family Devel¬opment, and British Columbia Early Learning Advisory Group.

Grissmer, D., Grimm, K.J., Aiyer, SM., Murrah, W. & Steele, J.S. (2010) ‘Fine motor skills and early comprehension of the world: two new school readiness indicators. Developmental psychology American psychological association, 46(5), pp. 10081017.

Jones, E. (2012) ‘The emergence of emergent curriculum’, YC Young children, 67(2), pp. 66-68.

Kashin, D. (2017) ‘What about the what? Finding the deeper meaning in pedagogical documentation’. Technology Rich Inquiry Based Research: Blog Available: https://tecribresearch.wordpress.com/2017/01/07/what-about-thewhat-finding-the-deeper-meaning-in-pedagogical-documentation, Accessed: 21 November 2018.

Lim, Seong Mi, (2016) Documenting the process of documentation: making teachers’ thinking visible. PHD Thesis. Kent State University, USA.

Melhuish, E. (2015) ‘What matters in the quality of ECEC?’ International policy event for early childhood education and care held in Dublin on 28th October 2015. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2U1zoC6EUbw.

Moss, P., Dillon, J. & Statham, J. (2000) ‘The “child in need” and “the rich child”: discourses, constructions and practice’, Critical social policy, 20(2), pp. 233-254.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2009) “Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children From Birth Through Age 8.” Position statement. Available at:

https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/ resources/position-statements/PSDAP.pdf

Navarrete, A. (2015) Assessment in the early years: the perspectives and practices of early childhood educators. Masters Dissertation, Dublin Institute of Technology.

NCCA (2009) Aistear Siolta Practice Guide: Helping young children develop positive dispositions for learning: Tip Sheet. Available at: https://www.ncca.ie/media/3193/dispositions-3-6.pdf

Ozgur, B. & Kantar, M. (n.d.) ‘Dynamic assessment (DA) & zone of proximal development (ZPD)’ [PowerPoint presentation]. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/8865573/Dynamic_Assessment_DA_and_Zone_of_Proximal_Development_ZPD (Accessed: 15 December 2018).

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D. & Jasper, M. (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Strong-Wilson, T. & Ellis, J. (2009) ‘Children and place: Reggio Emilia’s environment as third teacher’, Theory into practice, 46 (1), pp. 40-47.

Walsh, G., McGuinness, C., Sproule, L. & Trew, K. (2010) ‘Implementing a playbased and developmentally appropriate curriculum in Northern Ireland primary schools: what lessons have we learned?’, Early years, 30(1), pp.53-66.

Wien, C.A. (2008) Emergent curriculum in the primary classroom: Interpreting the Reggio Emilia approach in schools. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Wien, C.A., Guyevskey, V. & Berdoussis, N. (2011) ‘Learning to document in Reggio-inspired education’, Early childhood research and practice, 13(2). Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ956381.pdf

Wien, C.A. ‘Pedagogical documentation: looking deeper, an ongoing practice of making connections with children’s learning’. Interview with Professor Carol Wien. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyLpxMNbd-8

Wien, C.A. ‘Pedagogical documentation – making children’s learning and thinking visible’. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZfLUBDInAg

Wood, E. (2007) ‘New directions in play: consensus or collision?’, Education 3-13, 35 (4), pp. 309-320.

Wood, E. (2018) ‘Blending and transforming: children’s play time, space and places’. Presentation at Galway Childcare Committee ‘Time and Space’ Seminar. ILAS. National University of Ireland, Galway.

Wood, E. (2009) ‘Conceptualising a pedagogy of play: international perspectives from theory, policy and practice’, in Kuschner, D. (ed.) From children to red hatters: diverse images and issues of play. Play and culture studies. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. Vol. 8, pp. 166-89.

Wood, E. & Hedges, H. (2016) ‘Curriculum in early childhood education: critical questions about content, coherence, and control’, The curriculum journal, 27 (3), pp.387-405.

Web

Webinar: Pedagogical documentation. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y-iygDR49d0

Video

‘Play: Preschooler and toddler building with blocks’. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3f3rOz0NzPc

‘Thoughtful, intentional, provocations in FDK’. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CCb2KD6X8BU